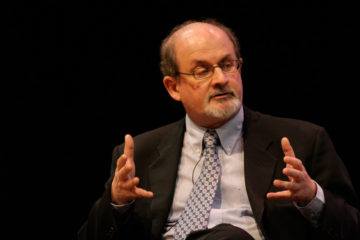

Faisal Devji in the Boston Review:

The brutal attack on novelist Salman Rushdie at a public lecture in Chautauqua, New York, last month has prompted a flood of revealing responses from liberals in the West. In the New Yorker, Adam Gopnik decried the enduring “terrorist” threat to “liberal civilization” in rhetoric that might well have been issued by the administration of George W. Bush. (Even law enforcement has declined to link the assault to terrorism.) Meanwhile, Graeme Wood, writing in the Atlantic, likens criticism of texts to complicity in assassination, while Bernard-Henri Lévy’s predictable diatribe against fanaticism calls for a “campaign” to “ensure” that Rushdie wins this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature—a cause New Yorker editor David Remnick has now joined, too. If it shocks us that the novelist was attacked after so long, it should also shock us that this commentary looks much the same as it did when his life was first threatened more than thirty years ago.

The brutal attack on novelist Salman Rushdie at a public lecture in Chautauqua, New York, last month has prompted a flood of revealing responses from liberals in the West. In the New Yorker, Adam Gopnik decried the enduring “terrorist” threat to “liberal civilization” in rhetoric that might well have been issued by the administration of George W. Bush. (Even law enforcement has declined to link the assault to terrorism.) Meanwhile, Graeme Wood, writing in the Atlantic, likens criticism of texts to complicity in assassination, while Bernard-Henri Lévy’s predictable diatribe against fanaticism calls for a “campaign” to “ensure” that Rushdie wins this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature—a cause New Yorker editor David Remnick has now joined, too. If it shocks us that the novelist was attacked after so long, it should also shock us that this commentary looks much the same as it did when his life was first threatened more than thirty years ago.

The defining feature of this genre of liberal exasperation is a dogmatic repudiation of history. In place of careful analysis of particular (and therefore changing) circumstances, it relies on stereotype and anecdote to depict a metaphysical conflict between religious fanaticism and liberal tolerance—one that is always and everywhere the same.

More here.

It was June, 1981. Elizabeth Hardwick was in Castine, the small town in Maine where she’d spent her summers for more than twenty years, since before her daughter, Harriet, was born. Even after Robert Lowell, her husband, left her, in 1970, she kept going. The flight from New York City to Bangor took only an hour; the rental car to Castine added another. “The drive is very nostalgia-creating,” she told me. When she arrived, she’d go grocery shopping, check in on the local couple who looked after the house for her, and be settled in by the time her old friend Mary McCarthy phoned. Mary and her husband had been coming to Castine almost as long as Elizabeth had. Mary lived on Main Street, but Elizabeth had remodelled a house on a bluff overlooking the water.

It was June, 1981. Elizabeth Hardwick was in Castine, the small town in Maine where she’d spent her summers for more than twenty years, since before her daughter, Harriet, was born. Even after Robert Lowell, her husband, left her, in 1970, she kept going. The flight from New York City to Bangor took only an hour; the rental car to Castine added another. “The drive is very nostalgia-creating,” she told me. When she arrived, she’d go grocery shopping, check in on the local couple who looked after the house for her, and be settled in by the time her old friend Mary McCarthy phoned. Mary and her husband had been coming to Castine almost as long as Elizabeth had. Mary lived on Main Street, but Elizabeth had remodelled a house on a bluff overlooking the water. Imagine you have 20 new compounds that have shown some effectiveness in treating a disease like tuberculosis (TB), which affects 10 million people worldwide and kills 1.5 million each year. For effective treatment, patients will need to take a combination of three or four drugs for months or even years because the TB bacteria behave differently in different environments in cells—and in some cases evolve to become drug-resistant. Twenty compounds in three- and four-drug combinations offer nearly 6,000 possible combinations. How do you decide which drugs to test together?

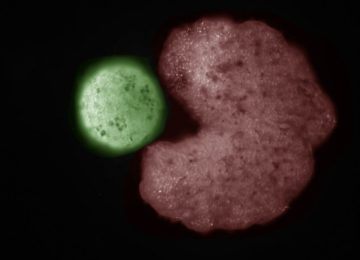

Imagine you have 20 new compounds that have shown some effectiveness in treating a disease like tuberculosis (TB), which affects 10 million people worldwide and kills 1.5 million each year. For effective treatment, patients will need to take a combination of three or four drugs for months or even years because the TB bacteria behave differently in different environments in cells—and in some cases evolve to become drug-resistant. Twenty compounds in three- and four-drug combinations offer nearly 6,000 possible combinations. How do you decide which drugs to test together? For Ellen Willis, feminism represented the possibility of being defiantly, boldly herself. Willis wasn’t so concerned with fitting into a single political camp; she loved, for example, rock and roll, even songs that had outrageously misogynistic lyrics. “Music that boldly and aggressively laid out what the singer wanted, loved, hated,” she wrote in an essay about bands such as the Sex Pistols and Ramones, “challenged me to do the same.” Meanwhile, she was bored by the “wimpiness” of milder, mellower, bands, including those that were explicitly feminist. Feminism allowed her to sort through these messy and incongruous pleasures freed from shame; to relish when her unruly feelings revealed a peculiar, unique kernel of self.

For Ellen Willis, feminism represented the possibility of being defiantly, boldly herself. Willis wasn’t so concerned with fitting into a single political camp; she loved, for example, rock and roll, even songs that had outrageously misogynistic lyrics. “Music that boldly and aggressively laid out what the singer wanted, loved, hated,” she wrote in an essay about bands such as the Sex Pistols and Ramones, “challenged me to do the same.” Meanwhile, she was bored by the “wimpiness” of milder, mellower, bands, including those that were explicitly feminist. Feminism allowed her to sort through these messy and incongruous pleasures freed from shame; to relish when her unruly feelings revealed a peculiar, unique kernel of self. Wilderson and Hartman insist that Afropessimism is not a politics (ARA 42–43, 56–57; SOS 65), but that demurral is either naïve or disingenuous. Counsel against pursuit of solidarities with nonblacks is a political stance and a potentially quite consequential one at that. And Afropessimism’s groupist focus proceeds from a class politics that represents the perspectives and concerns of a narrow stratum as those of the entire racialized population. Wilderson displays this class perspective in his romanticization of “Black suffering” (AP 328–331f).

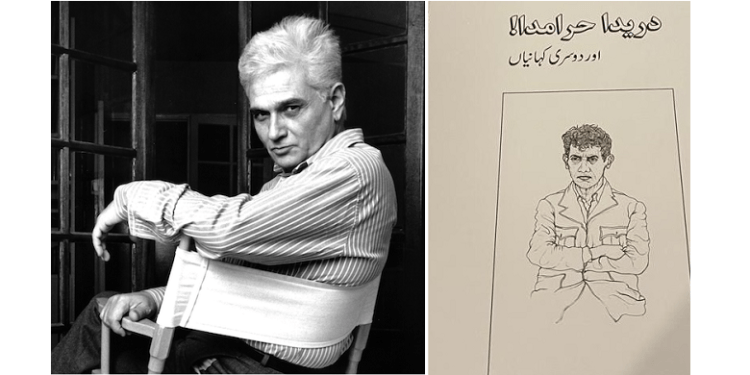

Wilderson and Hartman insist that Afropessimism is not a politics (ARA 42–43, 56–57; SOS 65), but that demurral is either naïve or disingenuous. Counsel against pursuit of solidarities with nonblacks is a political stance and a potentially quite consequential one at that. And Afropessimism’s groupist focus proceeds from a class politics that represents the perspectives and concerns of a narrow stratum as those of the entire racialized population. Wilderson displays this class perspective in his romanticization of “Black suffering” (AP 328–331f). The title story of Julien’s short story collection Derrida Haramda! introduces us to Shahid Wirk (or, as he is lovingly called by his friends, Sheeda) from Sheikhupura, who writes a surreal novel “Nazia” inspired by André Breton’s iconic surrealist work Nadja. Shahid’s novel is as an absurd piece of writing about a strange woman who haunts the streets of Sheikhupura. The narrator follows the woman at night, walking the city’s empty streets, and as he walks and walks, he is slowly confronted by the alienation he feels in the city, whose streets have emptied as if the city had been wiped clean of humans and animals by a poisonous gas. Julien’s stories often engage these peculiar and, at times, monstrous relationships and affiliations between European and South Asian creative work.

The title story of Julien’s short story collection Derrida Haramda! introduces us to Shahid Wirk (or, as he is lovingly called by his friends, Sheeda) from Sheikhupura, who writes a surreal novel “Nazia” inspired by André Breton’s iconic surrealist work Nadja. Shahid’s novel is as an absurd piece of writing about a strange woman who haunts the streets of Sheikhupura. The narrator follows the woman at night, walking the city’s empty streets, and as he walks and walks, he is slowly confronted by the alienation he feels in the city, whose streets have emptied as if the city had been wiped clean of humans and animals by a poisonous gas. Julien’s stories often engage these peculiar and, at times, monstrous relationships and affiliations between European and South Asian creative work. In one of the most dramatic demonstrations to date that cells are capable of more than we had imagined, the biologist Michael Levin of Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts and his colleagues have

In one of the most dramatic demonstrations to date that cells are capable of more than we had imagined, the biologist Michael Levin of Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts and his colleagues have  So argues

So argues  Scientists have developed a virus-killing plastic that could make it harder for bugs, including Covid, to spread in hospitals and care homes. The team at Queen’s University Belfast say their plastic film is cheap and could be fashioned into protective gear such as aprons. It works by reacting with light to release chemicals that break the virus. The study showed it could kill viruses by the million, even in tough species which linger on clothes and surfaces. The research was accelerated as part of the UK’s response to the Covid pandemic. Studies had shown the Covid virus

Scientists have developed a virus-killing plastic that could make it harder for bugs, including Covid, to spread in hospitals and care homes. The team at Queen’s University Belfast say their plastic film is cheap and could be fashioned into protective gear such as aprons. It works by reacting with light to release chemicals that break the virus. The study showed it could kill viruses by the million, even in tough species which linger on clothes and surfaces. The research was accelerated as part of the UK’s response to the Covid pandemic. Studies had shown the Covid virus  In late June, the US Supreme Court issued a trio of landmark decisions that repealed the right to abortion, loosened gun restrictions and

In late June, the US Supreme Court issued a trio of landmark decisions that repealed the right to abortion, loosened gun restrictions and  In her exquisitely written, perceptive, and moving Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (FSG, 2022), the British scholar Katherine Rundell argues that Donne’s “writing is itself a kind of alchemy: a mix of unlikely ingredients which spark into gold.” No 17th-century poet still reads quite as shockingly new as Donne does. Not

In her exquisitely written, perceptive, and moving Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (FSG, 2022), the British scholar Katherine Rundell argues that Donne’s “writing is itself a kind of alchemy: a mix of unlikely ingredients which spark into gold.” No 17th-century poet still reads quite as shockingly new as Donne does. Not  So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound.

So many accounts of Chekhov’s death, many of them exaggerated, some outright bogus. The only indisputable thing is that he died at forty-four. That’s etched in stone in Moscow. I like to read them anyway. I’m not alone. Chekhov death fanatics abound. Most of us have struggled to maintain our mental well-being throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by fear and apprehension, it’s been hard to keep hope alive. In my experience, those who have managed to find ways to feel useful have fared better than most. I was lucky: well before the sudden appearance of COVID-19, I had already been writing about our shared forms of vulnerability, global interdependencies, and the need to place the complexities of care at the very heart of politics. Even timelier, four friends had joined me to study our culture’s historic refusal to value care work. Our resulting small Care Collective quickly produced a book for Verso, The Care Manifesto (2020), keeping us all busier than ever, as we connected with others around the world who were also addressing the politics of care. As we developed our vision of a truly caring world, we focused on how governments, municipalities, and media outlets might become more caring, working to promote collective joy rather than their current narrow and duplicitous concern with individual aspiration, knowing that so many will inescapably flounder. Understanding that we all depend on each other, and nurturing rather than denying our interdependencies, encourages us all to work to cultivate a world in which each of us can not only live, but thrive.

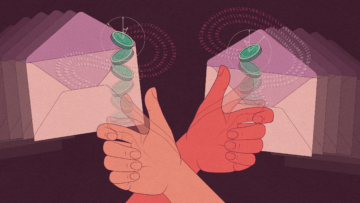

Most of us have struggled to maintain our mental well-being throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by fear and apprehension, it’s been hard to keep hope alive. In my experience, those who have managed to find ways to feel useful have fared better than most. I was lucky: well before the sudden appearance of COVID-19, I had already been writing about our shared forms of vulnerability, global interdependencies, and the need to place the complexities of care at the very heart of politics. Even timelier, four friends had joined me to study our culture’s historic refusal to value care work. Our resulting small Care Collective quickly produced a book for Verso, The Care Manifesto (2020), keeping us all busier than ever, as we connected with others around the world who were also addressing the politics of care. As we developed our vision of a truly caring world, we focused on how governments, municipalities, and media outlets might become more caring, working to promote collective joy rather than their current narrow and duplicitous concern with individual aspiration, knowing that so many will inescapably flounder. Understanding that we all depend on each other, and nurturing rather than denying our interdependencies, encourages us all to work to cultivate a world in which each of us can not only live, but thrive. If someone tells you a fact you already know, they’ve essentially told you nothing at all. Whereas if they impart a secret, it’s fair to say something has really been communicated.

If someone tells you a fact you already know, they’ve essentially told you nothing at all. Whereas if they impart a secret, it’s fair to say something has really been communicated. Overcoming the risk of “immiserizing” growth – an increase in aggregate national output that results in a net decline in national welfare – has been a perennial challenge as countries pursue economic development. It is also proving to be a major roadblock to achieving greater global income convergence.

Overcoming the risk of “immiserizing” growth – an increase in aggregate national output that results in a net decline in national welfare – has been a perennial challenge as countries pursue economic development. It is also proving to be a major roadblock to achieving greater global income convergence.