Nicholas Humphrey in Aeon:

Weiskrantz took a new approach with a human patient, known by the initials DB, who, after surgery to remove a growth affecting the visual cortex on the left side of his brain, was blind across the right-half field of vision. In the blind area, DB himself maintained that he had no visual awareness. Nonetheless, Weiskrantz asked him to guess the location and shape of an object that lay in this area. To everyone’s surprise, he consistently guessed correctly. To DB himself, his success in guessing seemed quite unreasonable. So far as he was concerned, he wasn’t the source of his perceptual judgments, his sight had nothing to do with him. Weiskrantz named this capacity ‘blindsight’: visual perception in the absence of any felt visual sensations.

Weiskrantz took a new approach with a human patient, known by the initials DB, who, after surgery to remove a growth affecting the visual cortex on the left side of his brain, was blind across the right-half field of vision. In the blind area, DB himself maintained that he had no visual awareness. Nonetheless, Weiskrantz asked him to guess the location and shape of an object that lay in this area. To everyone’s surprise, he consistently guessed correctly. To DB himself, his success in guessing seemed quite unreasonable. So far as he was concerned, he wasn’t the source of his perceptual judgments, his sight had nothing to do with him. Weiskrantz named this capacity ‘blindsight’: visual perception in the absence of any felt visual sensations.

Blindsight is now a well-established clinical phenomenon. When first discovered, it seemed theoretically shocking. No one had expected there could possibly be any such dissociation between perception and sensation. Yet, as I ruminated on the implications of it for understanding consciousness, I found myself doing a double-take. Perhaps the real puzzle is not so much the absence of sensation in blindsight as its presence in normal sight? If blindsight is seeing and nothingness, normal sight is seeing and somethingness. And surely it’s this something that stands in need of explanation.

More here.

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in around 1582, moved to Haarlem when he was three, found fame rather late, in his mid-thirties, died in 1666 – and was forgotten, at least outside his native country. The apparent lack of finish in his work made it unfashionable in the eyes of connoisseurs and collectors until interest in his paintings grew again in the mid-19th century. In 1865 Hals’s Laughing Cavalier was bought for a vast sum by Lord Hertford and exhibited in London to huge acclaim. Soon afterwards it entered the Wallace Collection.

Frans Hals was born in Antwerp in around 1582, moved to Haarlem when he was three, found fame rather late, in his mid-thirties, died in 1666 – and was forgotten, at least outside his native country. The apparent lack of finish in his work made it unfashionable in the eyes of connoisseurs and collectors until interest in his paintings grew again in the mid-19th century. In 1865 Hals’s Laughing Cavalier was bought for a vast sum by Lord Hertford and exhibited in London to huge acclaim. Soon afterwards it entered the Wallace Collection. A team of computer scientists has come up with a

A team of computer scientists has come up with a  In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “

In September 2016 I gave a lecture at Duke University: “ Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, died on September 16th in Tehran after being detained and allegedly beaten by Iran’s  The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer.

The first therapeutic cancer vaccine, approved more than a decade ago, targeted prostate tumours. The treatment involves extracting antigen-presenting cells — a component of the immune system that tells other cells what to target — from a person’s blood, loading them with a marker found on prostate tumours, and then returning them to the patient. The idea is that other immune cells will then take note and attack the cancer. The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural:

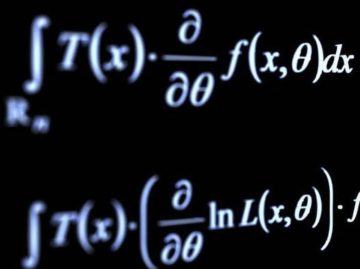

The signaling behavior of human beings is intricate indeed. Forty years ago a man, seething with desire, issued forth a string of identical second-person singular imperatives followed by a hortatory first-person plural: The aim of my piece was to challenge the popular notion that mathematics is synonymous with calculation. Starting with arithmetic and proceeding through algebra and beyond, the message drummed into our heads as students is that we do math to “get the right answer.” The drill of multiplication tables, the drudgery of long division, the quadratic formula and its memorization—these are the dreary memories many of us carry around from school as a result.

The aim of my piece was to challenge the popular notion that mathematics is synonymous with calculation. Starting with arithmetic and proceeding through algebra and beyond, the message drummed into our heads as students is that we do math to “get the right answer.” The drill of multiplication tables, the drudgery of long division, the quadratic formula and its memorization—these are the dreary memories many of us carry around from school as a result. The recent debate over “presentism” among historians, especially those based in the United States, has generated both heat and light. It is a useful conversation to have now, at a moment when the public sphere, and even more so the university’s space within it, seems to consist more of mines than of fields. Debates about Covid-19, affirmative (in)action, antisemitism, sexual violence, student debt, Title IX, Confederate monuments, racist donors, resigning presidents, and rogue trustees combine to occlude the daylight of classes, books, and learning.

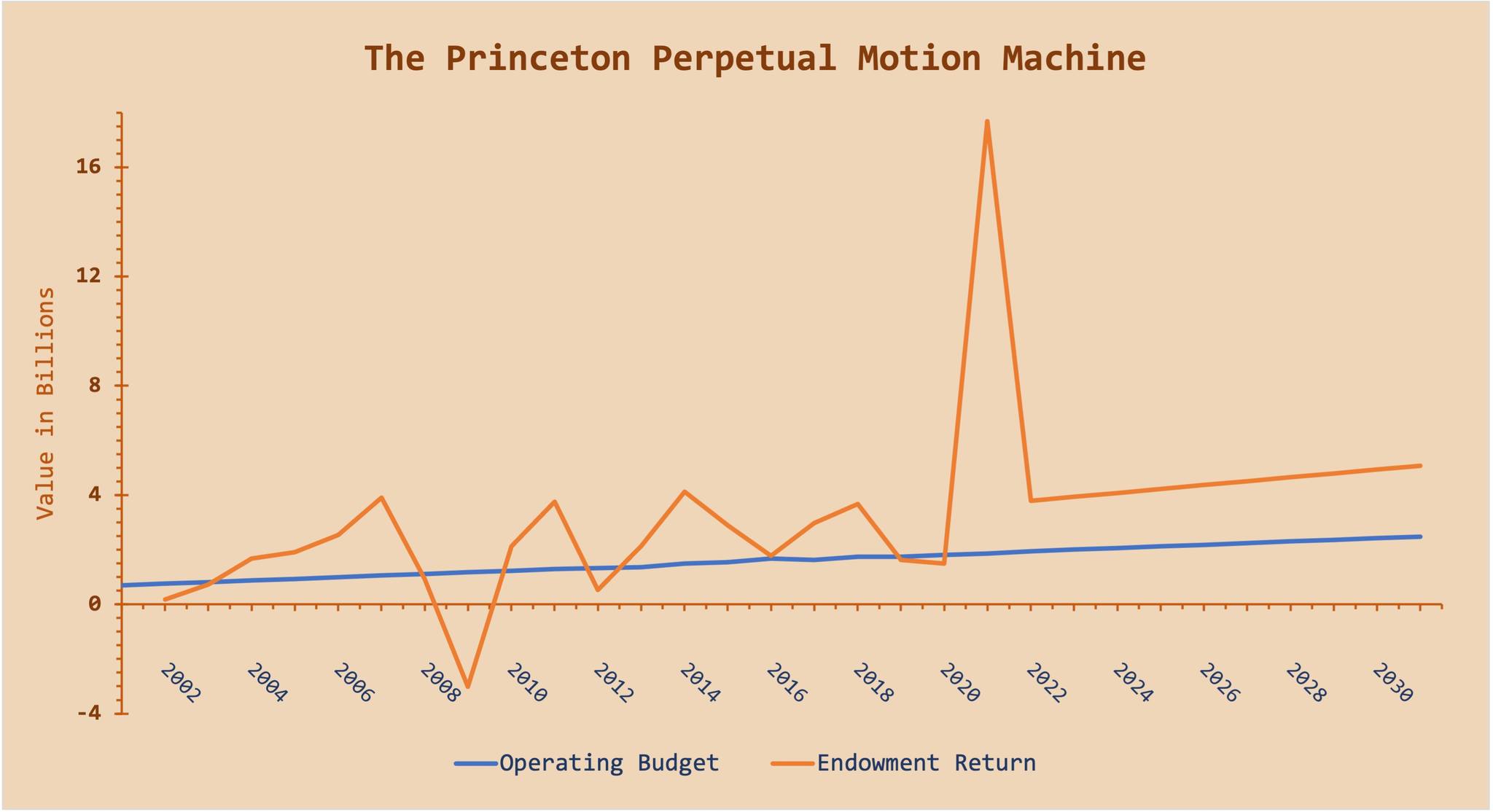

The recent debate over “presentism” among historians, especially those based in the United States, has generated both heat and light. It is a useful conversation to have now, at a moment when the public sphere, and even more so the university’s space within it, seems to consist more of mines than of fields. Debates about Covid-19, affirmative (in)action, antisemitism, sexual violence, student debt, Title IX, Confederate monuments, racist donors, resigning presidents, and rogue trustees combine to occlude the daylight of classes, books, and learning. After a stellar year in 2021, Princeton University has an endowment of $37.7 billion. Over the past 20 years, the average annual return for the endowment has been 11.2 percent. Let us give Princeton the benefit of the doubt and assume that at least some of that was luck and maybe unsustainable, and that a more reasonable prediction going forward would be that Princeton can average a return on its investments of an even 10 percent a year. That puts Princeton’s endowment return next year at roughly $3.77 billion.

After a stellar year in 2021, Princeton University has an endowment of $37.7 billion. Over the past 20 years, the average annual return for the endowment has been 11.2 percent. Let us give Princeton the benefit of the doubt and assume that at least some of that was luck and maybe unsustainable, and that a more reasonable prediction going forward would be that Princeton can average a return on its investments of an even 10 percent a year. That puts Princeton’s endowment return next year at roughly $3.77 billion. “D

“D Zan, Zendegi, Azadi: Woman! Life! Freedom!

Zan, Zendegi, Azadi: Woman! Life! Freedom!