A Game of Chess

In Washington Square Park, astonishing late October

turns a yellow leaf as airily as spring.

Everything slices up the light—the office towers,

the bough above a woman cutting a man’s hair

by the finished roses. Water blazes from the fountain

and bible quotes done in chalk are dust beneath

the feet of the fiddler playing bluegrass for a few coins.

It is so very hard to get close to anything.

Over where the public chess tables

stand in latticed shade, their concentration

makes the players seem all of a piece,

and the heart wants to sleep. But even here

a small upheaval . . .

A black man, serious and soft, and a white boy

maybe ten years old, pressed into his sharp collared shirt,

engage in the abstract and the real.

Here, I am given the space to see

the boy let go his queen

too soon, the look on his face.

The man takes the queen away

and the empty square is an immensity

the boy cannot move

then the man succeeds in taking us all in

when he puts her back contrariwise,

leans and smiles—Don’t you be doing that again.

And a boy grows in the light, and a man loses

because he loves. And all the season does

is throw down leaves and divvy up the sun

above the chessmen on their chequered field.

by Cally Conan-Davies

from the Hudson Review

THERE IS NO other novel quite like Michael Fessier’s 1935 genre-bending Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind. At first glance, the San Francisco–set tale is classic noir, narrated in the steely patter of Depression-era hard-boiled crime fiction. An average Joe, John Price, happens upon a murder in the street; he then becomes unwillingly entangled in the perpetrator’s subsequent killings; and finally, he must prove his innocence when the police try to railroad Price for the other’s crimes. But what elevates Fully Dressed into a class all its own is how Fessier incorporates fantastical characters and events that are alien to noir. The incongruity between the novel’s deadpan, tough-guy prose and its wildly surreal content makes Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind a haunting novel that’s impossible to put down.

THERE IS NO other novel quite like Michael Fessier’s 1935 genre-bending Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind. At first glance, the San Francisco–set tale is classic noir, narrated in the steely patter of Depression-era hard-boiled crime fiction. An average Joe, John Price, happens upon a murder in the street; he then becomes unwillingly entangled in the perpetrator’s subsequent killings; and finally, he must prove his innocence when the police try to railroad Price for the other’s crimes. But what elevates Fully Dressed into a class all its own is how Fessier incorporates fantastical characters and events that are alien to noir. The incongruity between the novel’s deadpan, tough-guy prose and its wildly surreal content makes Fully Dressed and in His Right Mind a haunting novel that’s impossible to put down. What books would you recommend to somebody who wants to understand present-day Japan?

What books would you recommend to somebody who wants to understand present-day Japan? Just how anti-American is Pakistan?

Just how anti-American is Pakistan? In “

In “ Tycoons are susceptible to the misconception that if you know how to make billions you know how to spend them. Sam Bankman-Fried, the “

Tycoons are susceptible to the misconception that if you know how to make billions you know how to spend them. Sam Bankman-Fried, the “ A ROMANIAN FILMMAKER who regularly deflates Romanian myths of national greatness, Radu Jude recently graced the New York Film Festival with a compact, farcical essay on the material basis of historical memory, or, to use Trotsky’s term, “the dustbin of history.”

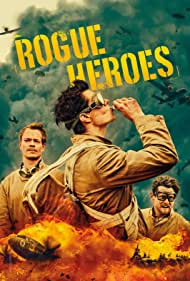

A ROMANIAN FILMMAKER who regularly deflates Romanian myths of national greatness, Radu Jude recently graced the New York Film Festival with a compact, farcical essay on the material basis of historical memory, or, to use Trotsky’s term, “the dustbin of history.” The creation of Steven Knight of Peaky Blinders fame, it shares with that series a fondness for mythologising and aphoristic dialogue. Set in the Egyptian desert in 1941 as the British army struggles to defend besieged Tobruk from the Germans, its tone is midway between the war comics my brother used to read as a boy (he favoured Battle) and a Duran Duran video – and I mean this as a compliment.

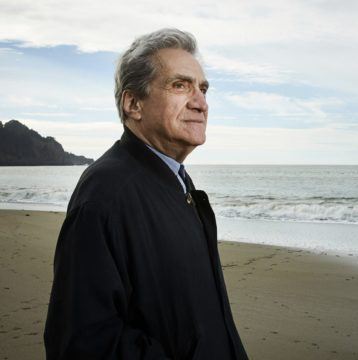

The creation of Steven Knight of Peaky Blinders fame, it shares with that series a fondness for mythologising and aphoristic dialogue. Set in the Egyptian desert in 1941 as the British army struggles to defend besieged Tobruk from the Germans, its tone is midway between the war comics my brother used to read as a boy (he favoured Battle) and a Duran Duran video – and I mean this as a compliment. It is hard to imagine anyone who has done more to champion poetry than Robert Pinsky. The author of 10 collections of poems—including the Pulitzer Prize–nominated The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems, 1966-1996—Pinsky has edited anthologies, written more than a half-dozen prose books about poetry, and translated Dante’s Inferno and the poems of Czesław Miłosz. As director of

It is hard to imagine anyone who has done more to champion poetry than Robert Pinsky. The author of 10 collections of poems—including the Pulitzer Prize–nominated The Figured Wheel: New and Collected Poems, 1966-1996—Pinsky has edited anthologies, written more than a half-dozen prose books about poetry, and translated Dante’s Inferno and the poems of Czesław Miłosz. As director of  Trans people’s right to exist

Trans people’s right to exist  It has been more than two decades since the issue of “loss and damage” was first raised at a UN climate summit.

It has been more than two decades since the issue of “loss and damage” was first raised at a UN climate summit. Tim Michels, a wealthy sixty-year-old businessman, was the Republican nominee for governor of Wisconsin. During the primary, when asked whether the 2020 Presidential election had been stolen, Michels said, “Maybe.” A few months later, he said that, if he became governor, Republicans would “never lose an election in Wisconsin again.” Given the context, it was hard to know whether that was normal political braggadocio or a statement of intent. Donald Trump came to Wisconsin to campaign for Michels, who made election integrity, as he put it, a big part of his pitch. He proposed to eliminate the nonpartisan agency that oversees the state’s elections and replace it with a new entity whose composition and mission was left a little hazy.

Tim Michels, a wealthy sixty-year-old businessman, was the Republican nominee for governor of Wisconsin. During the primary, when asked whether the 2020 Presidential election had been stolen, Michels said, “Maybe.” A few months later, he said that, if he became governor, Republicans would “never lose an election in Wisconsin again.” Given the context, it was hard to know whether that was normal political braggadocio or a statement of intent. Donald Trump came to Wisconsin to campaign for Michels, who made election integrity, as he put it, a big part of his pitch. He proposed to eliminate the nonpartisan agency that oversees the state’s elections and replace it with a new entity whose composition and mission was left a little hazy. There’s an age-old adage in biology: structure determines function. In order to understand the function of the myriad proteins that perform vital jobs in a healthy body—or malfunction in a diseased one—scientists have to first determine these proteins’ molecular structure. But this is no easy feat: protein molecules consist of long, twisty chains of up to thousands of amino acids, chemical compounds that can interact with one another in many ways to take on an enormous number of possible three-dimensional shapes. Figuring out a single protein’s structure, or solving the “protein-folding problem,” can take years of finicky experiments.

There’s an age-old adage in biology: structure determines function. In order to understand the function of the myriad proteins that perform vital jobs in a healthy body—or malfunction in a diseased one—scientists have to first determine these proteins’ molecular structure. But this is no easy feat: protein molecules consist of long, twisty chains of up to thousands of amino acids, chemical compounds that can interact with one another in many ways to take on an enormous number of possible three-dimensional shapes. Figuring out a single protein’s structure, or solving the “protein-folding problem,” can take years of finicky experiments. Since 1994 midterms have mattered, not just as protest votes, but as elections that have frequently determined congressional control. In the last eight midterms, control of the House has changed hands either four or five times (depending on the final 2022 result), while it’s only been twice in the Senate. Midterms have become a true political thermostat, and the result has often been divided government for the last two years of a Presidential term. Consequently, the typical second half of a Presidency is now legislative gridlock, occasional cross-party compromise, stacks of Executive Orders, and a sharp uptick in Presidential overseas trips to get away from the unpleasantness in DC.

Since 1994 midterms have mattered, not just as protest votes, but as elections that have frequently determined congressional control. In the last eight midterms, control of the House has changed hands either four or five times (depending on the final 2022 result), while it’s only been twice in the Senate. Midterms have become a true political thermostat, and the result has often been divided government for the last two years of a Presidential term. Consequently, the typical second half of a Presidency is now legislative gridlock, occasional cross-party compromise, stacks of Executive Orders, and a sharp uptick in Presidential overseas trips to get away from the unpleasantness in DC.