Peter Attia in peterattiamd.com:

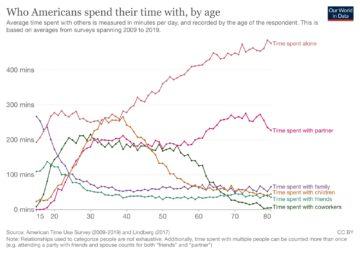

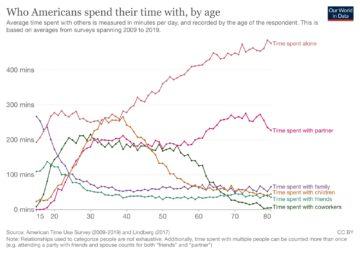

I recently shared a graph on Instagram representing whom we spend time with across our lifetime, collected from 2009 to 2019 as part of the American Time Use Survey (Figure 1). For the most part, the numbers make intuitive sense. The amount of time we spend with our coworkers starts dropping in our mid-fifties as we begin to retire, and time with partners rises concurrently. Time spent with children spikes during the typical child-bearing years of our twenties and thirties and falls again as we reach the “empty nest” stage.

I recently shared a graph on Instagram representing whom we spend time with across our lifetime, collected from 2009 to 2019 as part of the American Time Use Survey (Figure 1). For the most part, the numbers make intuitive sense. The amount of time we spend with our coworkers starts dropping in our mid-fifties as we begin to retire, and time with partners rises concurrently. Time spent with children spikes during the typical child-bearing years of our twenties and thirties and falls again as we reach the “empty nest” stage.

Figure 1: Who Americans spend their time with, by age.

These data demonstrate that most of us enjoy a diversity of social connections daily, and yet, throughout virtually all of our lifespan, we spend more time alone than with any given relationship. Especially eye-catching is the rapid increase in time spent alone after the age of forty, and beyond our early sixties, we spend, on average, more than seven waking hours alone.

Guaranteed loneliness?

The same article, published by Our World in Data, interestingly shows that the percentage of Americans living alone across all age groups has been increasing throughout history, as shown in Figure 2 (one exception being a recent decline in the age 75 group, though this is likely an artifact of increased life expectancy). In just the past half-century, the proportion of people living alone has almost doubled. In fact, more than 40% of people over the age of 89 live alone. So not only do we spend more time alone as we age, we also spend more time alone than our historical counterparts at all ages. These combined trends raise the question: are we growing lonely?

Despite these statistics, time spent alone does not reflect a loss of meaningful social connection and does not predict loneliness.

More here.

The Feelies never quite belonged to the “blank generation,” a term coined by punk rocker Richard Hell that describes the midseventies New York punk scene. They certainly played alongside the likes of Television, the Patti Smith Group, the Shirts, and other CBGB and Max’s Kansas City mainstays, but they never quite gelled with that crowd. Their sound was more angular and percussive than the shambolic style of their peers. They were the jangly alternative to the alternative culture, exemplifying a vibrant sonic quality that strongly influenced early R.E.M. and almost every other band that critics would eventually label “college rock.” Perhaps the twin rhythm guitar and percussion sections contributed to their outsider status. Or maybe they never quite belonged because Glenn Mercer and Bill Million, the founding members, hail from suburban New Jersey.

The Feelies never quite belonged to the “blank generation,” a term coined by punk rocker Richard Hell that describes the midseventies New York punk scene. They certainly played alongside the likes of Television, the Patti Smith Group, the Shirts, and other CBGB and Max’s Kansas City mainstays, but they never quite gelled with that crowd. Their sound was more angular and percussive than the shambolic style of their peers. They were the jangly alternative to the alternative culture, exemplifying a vibrant sonic quality that strongly influenced early R.E.M. and almost every other band that critics would eventually label “college rock.” Perhaps the twin rhythm guitar and percussion sections contributed to their outsider status. Or maybe they never quite belonged because Glenn Mercer and Bill Million, the founding members, hail from suburban New Jersey.

In his 1987 book Die Schrift, the Czech-born Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser posed the question of whether writing had a future (Hat Schreiben Zukunft? reads Flusser’s subtitle). As he surveyed the media landscape of the late twentieth century, Flusser observed that some aspects of writing (“this ordering of written signs into rows”) could already be “mechanized and automated” thanks to word processing, and he foresaw that artificial intelligence would “surely become more intelligent in the future” allowing the mechanization of writing to proceed further.

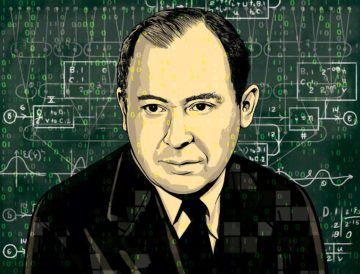

In his 1987 book Die Schrift, the Czech-born Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser posed the question of whether writing had a future (Hat Schreiben Zukunft? reads Flusser’s subtitle). As he surveyed the media landscape of the late twentieth century, Flusser observed that some aspects of writing (“this ordering of written signs into rows”) could already be “mechanized and automated” thanks to word processing, and he foresaw that artificial intelligence would “surely become more intelligent in the future” allowing the mechanization of writing to proceed further. Unlike his much more famous colleague Albert Einstein, John von Neumann is not a household name these days, but his discoveries shape the possibilities of life for every creature on this planet. As a teenager, von Neumann provided mathematics with new foundations. He later helped teach the world how to build and detonate nuclear bombs. His invention of game theory furnished the conceptual tools with which superpowers today decide whether to wage war, economists model the behavior of markets, and biologists predict the evolution of viruses. The pioneering programmable computer that von Neumann and his employer, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., completed in 1951 established “von Neumann architecture” as the standard for computer design well into the 21st century, making first IBM and then many other corporations fabulously wealthy.

Unlike his much more famous colleague Albert Einstein, John von Neumann is not a household name these days, but his discoveries shape the possibilities of life for every creature on this planet. As a teenager, von Neumann provided mathematics with new foundations. He later helped teach the world how to build and detonate nuclear bombs. His invention of game theory furnished the conceptual tools with which superpowers today decide whether to wage war, economists model the behavior of markets, and biologists predict the evolution of viruses. The pioneering programmable computer that von Neumann and his employer, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., completed in 1951 established “von Neumann architecture” as the standard for computer design well into the 21st century, making first IBM and then many other corporations fabulously wealthy. For warming to be limited to 1.5 °C, emissions need to fall by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030. According to the

For warming to be limited to 1.5 °C, emissions need to fall by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030. According to the  It’s easy to look at a forest and think it’s inevitable: that the trees came into being through a stately procession of seasons and seeds and soil, and will replenish themselves so long as environmental conditions allow. Hidden from sight are the creatures whose labor makes the forest possible — the multitudes of microorganisms and invertebrates involved in maintaining that soil, and the animals responsible for delivering seeds too heavy to be wind-borne to the places where they will sprout. If one is interested in the future of a forest — which tree species will thrive and which will diminish, or whether those threatened by a fast-changing climate will successfully migrate to newly hospitable lands — one should look to these seed-dispersing animals.

It’s easy to look at a forest and think it’s inevitable: that the trees came into being through a stately procession of seasons and seeds and soil, and will replenish themselves so long as environmental conditions allow. Hidden from sight are the creatures whose labor makes the forest possible — the multitudes of microorganisms and invertebrates involved in maintaining that soil, and the animals responsible for delivering seeds too heavy to be wind-borne to the places where they will sprout. If one is interested in the future of a forest — which tree species will thrive and which will diminish, or whether those threatened by a fast-changing climate will successfully migrate to newly hospitable lands — one should look to these seed-dispersing animals. Donne was not sent to school. He was missing very little; the schools of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were grim, ice cold metaphorically and literally. Eton’s dormitory was full of rats; at many of the public schools at the time, the boys burned the furniture to keep warm, threw each other around in their blankets, broke each other’s ribs and occasionally heads. The Merchant Taylors’ school had in its rules the stipulation, ‘unto their urine the scholars shall go to the places appointed them in the lane or street without the court’, which, assuming the interdiction was necessary for a reason, suggests the school would have smelled strongly of youthful pee. Because smoking was believed to keep the plague at bay, at Eton they were flogged for the crime of not smoking. Discipline could be murderous. It became necessary to enforce startling legal limits: ‘when a schoolmaster, in correcting his scholar, happens to occasion his death, if in such correction he is so barbarous as to exceed all bounds of moderation, he is at least guilty of manslaughter; and if he makes use of an instrument improper for correction, as an iron bar or sword … he is guilty of murder.’

Donne was not sent to school. He was missing very little; the schools of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were grim, ice cold metaphorically and literally. Eton’s dormitory was full of rats; at many of the public schools at the time, the boys burned the furniture to keep warm, threw each other around in their blankets, broke each other’s ribs and occasionally heads. The Merchant Taylors’ school had in its rules the stipulation, ‘unto their urine the scholars shall go to the places appointed them in the lane or street without the court’, which, assuming the interdiction was necessary for a reason, suggests the school would have smelled strongly of youthful pee. Because smoking was believed to keep the plague at bay, at Eton they were flogged for the crime of not smoking. Discipline could be murderous. It became necessary to enforce startling legal limits: ‘when a schoolmaster, in correcting his scholar, happens to occasion his death, if in such correction he is so barbarous as to exceed all bounds of moderation, he is at least guilty of manslaughter; and if he makes use of an instrument improper for correction, as an iron bar or sword … he is guilty of murder.’ Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh.

Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh. An experimental

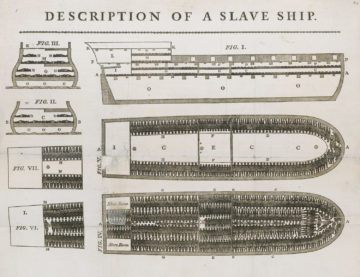

An experimental  Asterisk: Your book Moral Capital is about why the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain happened in the late 1780s and not earlier. Would you mind briefly walking through the thrust of that argument?

Asterisk: Your book Moral Capital is about why the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain happened in the late 1780s and not earlier. Would you mind briefly walking through the thrust of that argument? 3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

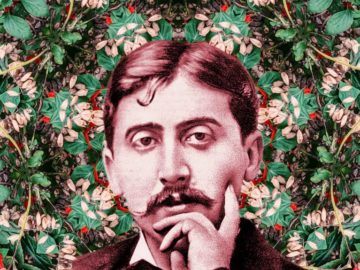

3:16: What made you become a philosopher? One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“

One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“ I recently shared a

I recently shared a  Michael Pettis in American Compass:

Michael Pettis in American Compass: Martijn Konings in Sidecar:

Martijn Konings in Sidecar: Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World: Mona Ali in Green:

Mona Ali in Green: