Christopher Bonanos at Vulture:

Rosalind Fox Solomon has almost never worked on assignment. When she first started taking photographs with an idea of making art, no one would have expected her to turn that into a career; she was heading into her 40s with two children, a woman learning to communicate as she hadn’t been able to before. She started out shooting close to her home in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Even after she started gaining recognition and traveling farther afield, she didn’t exactly have a long-term plan: She would, she says, just decide to go somewhere — occasionally because of a disruptive event, like an earthquake or a flood, but usually just because, hiring a guide and a translator if she needed one. In India, Guatemala, Brazil, or Missouri, she’d move around and look at people, engaging them but not saying much, and come back with pictures. That’s it.

Rosalind Fox Solomon has almost never worked on assignment. When she first started taking photographs with an idea of making art, no one would have expected her to turn that into a career; she was heading into her 40s with two children, a woman learning to communicate as she hadn’t been able to before. She started out shooting close to her home in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Even after she started gaining recognition and traveling farther afield, she didn’t exactly have a long-term plan: She would, she says, just decide to go somewhere — occasionally because of a disruptive event, like an earthquake or a flood, but usually just because, hiring a guide and a translator if she needed one. In India, Guatemala, Brazil, or Missouri, she’d move around and look at people, engaging them but not saying much, and come back with pictures. That’s it.

Did she think about what collectors or publishers or editors might want, the way so many photographers do? “First of all, I’ve never been commercially viable,” Fox Solomon says now. “I never thought about that. Really, I just worked. Piled up my prints, year after year.”

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Christopher Marlowe is having a moment. In London’s West End, the Royal Shakespeare Company is staging Born with Teeth, a new play by Liz Duffy Adams that imagines the erotic tension crackling between Marlowe and Shakespeare as they collaborate on Henry VI. And right on cue comes the first major biography of Marlowe in two decades, written by the unquestioned eminence of Shakespearean new historicism. This is in some ways a counterpoint to Will in the World, Stephen Greenblatt’s gloriously rich evocation of the early modern culture that nourished Shakespeare’s creative genius. It was Greenblatt more than anyone else who taught us to understand the writer by examining the society in which he or she lived, but in Dark Renaissance the Greenblattian method is turned on its head. He shows us an Elizabethan England altogether too small, bigoted and fearful to account for the emergence of a shooting star like Marlowe.

Christopher Marlowe is having a moment. In London’s West End, the Royal Shakespeare Company is staging Born with Teeth, a new play by Liz Duffy Adams that imagines the erotic tension crackling between Marlowe and Shakespeare as they collaborate on Henry VI. And right on cue comes the first major biography of Marlowe in two decades, written by the unquestioned eminence of Shakespearean new historicism. This is in some ways a counterpoint to Will in the World, Stephen Greenblatt’s gloriously rich evocation of the early modern culture that nourished Shakespeare’s creative genius. It was Greenblatt more than anyone else who taught us to understand the writer by examining the society in which he or she lived, but in Dark Renaissance the Greenblattian method is turned on its head. He shows us an Elizabethan England altogether too small, bigoted and fearful to account for the emergence of a shooting star like Marlowe. There’s a certain flavor of advice that is dominating the self-help best-seller list. These books have titles like “The Courage to Be Disliked” and “Set Boundaries, Find Peace.” They tell readers not to worry so much about letting people down, not to answer those calls from aggravating friends, not to be afraid of being the villain.

There’s a certain flavor of advice that is dominating the self-help best-seller list. These books have titles like “The Courage to Be Disliked” and “Set Boundaries, Find Peace.” They tell readers not to worry so much about letting people down, not to answer those calls from aggravating friends, not to be afraid of being the villain.

Arundhati Roy identifies as a vagrant. There was a moment in 1997, right after the Delhi-based writer became the first Indian citizen to win the Booker Prize, for her best-selling debut, The God of Small Things, when the president and the prime minister claimed the whole country was proud of her. She was 36 and suddenly rich; she could have coasted on the money and praise. Instead, she changed direction. Furiously and at length, she started writing essays for Indian magazines about everything her country’s elites were doing wrong. As nationalists celebrated Indian nuclear tests, she wrote, “The air is thick with ugliness and there’s the unmistakable stench of fascism on the breeze.” In another essay: “On the whole, in India, the prognosis is — to put it mildly — Not Good.” She wrote about Hindu-nationalist violence, military occupation in Kashmir, poverty, displacement, Islamophobia, and corporate crimes. Her anti-patriotic turn got her dragged in the press and then to court on charges that ranged from obscenity (for a cross-caste sex scene in The God of Small Things) to, most recently, terrorism. She began to define herself against the conflict. As Roy writes in Mother Mary Comes to Me, her new memoir, “The more I was hounded as an antinational, the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged. Where else could I be the hooligan that I was becoming? Where else would I find co-hooligans I so admired?”

Arundhati Roy identifies as a vagrant. There was a moment in 1997, right after the Delhi-based writer became the first Indian citizen to win the Booker Prize, for her best-selling debut, The God of Small Things, when the president and the prime minister claimed the whole country was proud of her. She was 36 and suddenly rich; she could have coasted on the money and praise. Instead, she changed direction. Furiously and at length, she started writing essays for Indian magazines about everything her country’s elites were doing wrong. As nationalists celebrated Indian nuclear tests, she wrote, “The air is thick with ugliness and there’s the unmistakable stench of fascism on the breeze.” In another essay: “On the whole, in India, the prognosis is — to put it mildly — Not Good.” She wrote about Hindu-nationalist violence, military occupation in Kashmir, poverty, displacement, Islamophobia, and corporate crimes. Her anti-patriotic turn got her dragged in the press and then to court on charges that ranged from obscenity (for a cross-caste sex scene in The God of Small Things) to, most recently, terrorism. She began to define herself against the conflict. As Roy writes in Mother Mary Comes to Me, her new memoir, “The more I was hounded as an antinational, the surer I was that India was the place I loved, the place to which I belonged. Where else could I be the hooligan that I was becoming? Where else would I find co-hooligans I so admired?” In 2023 — just as ChatGPT was hitting 100 million monthly users, with a large minority of them freaking out about living inside the movie “Her” — the artificial intelligence researcher Katja Grace published an intuitively disturbing industry survey that

In 2023 — just as ChatGPT was hitting 100 million monthly users, with a large minority of them freaking out about living inside the movie “Her” — the artificial intelligence researcher Katja Grace published an intuitively disturbing industry survey that  Pick up

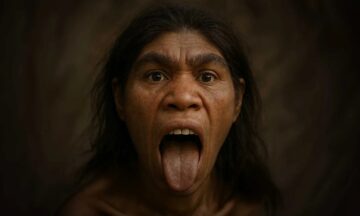

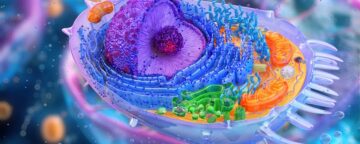

Pick up  On the long arm of chromosome 12 is a gene called MUC19. It’s one of a family of genes that encode proteins called mucins, which provide mucus and mucus membranes their slippery, gelatinous consistency.

On the long arm of chromosome 12 is a gene called MUC19. It’s one of a family of genes that encode proteins called mucins, which provide mucus and mucus membranes their slippery, gelatinous consistency. There was a time in 2016 when I walked around downtown San Francisco with Dan Wang and gave him life advice. He asked me if he should move to China and write about it. I told him that I thought this was a good idea — that the world suffered from a strange and troubling dearth of people who write informatively about China in English, and that our country would be better off if we could understand China a little more.

There was a time in 2016 when I walked around downtown San Francisco with Dan Wang and gave him life advice. He asked me if he should move to China and write about it. I told him that I thought this was a good idea — that the world suffered from a strange and troubling dearth of people who write informatively about China in English, and that our country would be better off if we could understand China a little more. William Goldman wasn’t a great writer, at least not according to traditional standards. His prose, at its best, was like a milkshake: fast and tasty, with the occasional clog. At its worst, his prose could be both chatty and flat, which, like being interestingly dull, is hard to pull off. Goldman was famous for his writing speed, knocking out novels in just weeks. He was equally famous—or, rather, infamous—for his aversion to rewriting. But there has never been another writer quite like him.

William Goldman wasn’t a great writer, at least not according to traditional standards. His prose, at its best, was like a milkshake: fast and tasty, with the occasional clog. At its worst, his prose could be both chatty and flat, which, like being interestingly dull, is hard to pull off. Goldman was famous for his writing speed, knocking out novels in just weeks. He was equally famous—or, rather, infamous—for his aversion to rewriting. But there has never been another writer quite like him. A

A  T

T