Kevin Hurler at Gizmodo:

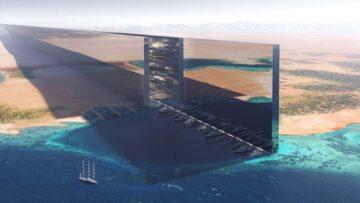

The future starts now? Drone footage shows construction beginning on Saudi Arabia’s sci-fi megacity called The Line—a city planned to be 105 miles (170 kilometers) long that people can live and work in without ever leaving.

The future starts now? Drone footage shows construction beginning on Saudi Arabia’s sci-fi megacity called The Line—a city planned to be 105 miles (170 kilometers) long that people can live and work in without ever leaving.

As another day of failed cryptocurrency companies and Big Brother watching us passes, it truly feels like we are inching ever-closer to a bleak future from a sci-fi novel—the only thing we’ve really been missing is a futuristic megalopolis. Saudi Arabia’s The Line caught headlines this past summer for its sleek and arguably unnecessary approach to a city—featuring a mirrored exterior that contains a completely self-contained city that is 546 yards (500 meters) tall, 218 yards (200 meters) wide, and a whopping 105 miles (170 kilometers) long. While the knee-jerk reaction was rampant skepticism over when and how this monstrosity would ever get off the ground, new footage from Saudi Arabia confirms that The Line is officially a work in progress.

more here.

Humans are weird

Humans are weird It’s easy enough to proclaim that we are curious creatures, but what does that really mean? What kinds of curiosity are there? And how does curiosity arise in our brains? Perry Zurn and Dani Bassett are a philosopher and neuroscientist, respectively (as well as twins), whose new book

It’s easy enough to proclaim that we are curious creatures, but what does that really mean? What kinds of curiosity are there? And how does curiosity arise in our brains? Perry Zurn and Dani Bassett are a philosopher and neuroscientist, respectively (as well as twins), whose new book  Ken Kesey (1935–2001) was a great admirer of manliness, a quality that would inform his countercultural indictment of America’s attitude toward mental illness, and of postwar America more generally. The darkly comic 1962 novel for which he is known,

Ken Kesey (1935–2001) was a great admirer of manliness, a quality that would inform his countercultural indictment of America’s attitude toward mental illness, and of postwar America more generally. The darkly comic 1962 novel for which he is known,  A FEW WEEKS AGO

A FEW WEEKS AGO Every multicellular organism begins as one cell, which contains all of the intricate instructions to synthesize, organize, and regulate not only this cell but the development and maintenance of all cells that will inevitably comprise the organism. All of these instructions are encoded in the first cell’s DNA. This underscores the complexity of the genome and how each cell’s expression must be controlled in specific ways depending on its function. The cells hailing from each tissue in the human body (e.g., muscle, lung, heart, liver) harbor a unique epigenetic signature, which enables the maintenance of tissue-specific functions through the control of gene regulation, as just discussed.

Every multicellular organism begins as one cell, which contains all of the intricate instructions to synthesize, organize, and regulate not only this cell but the development and maintenance of all cells that will inevitably comprise the organism. All of these instructions are encoded in the first cell’s DNA. This underscores the complexity of the genome and how each cell’s expression must be controlled in specific ways depending on its function. The cells hailing from each tissue in the human body (e.g., muscle, lung, heart, liver) harbor a unique epigenetic signature, which enables the maintenance of tissue-specific functions through the control of gene regulation, as just discussed. As the story is often told, even before the era of manned lunar exploration ended, policymakers and the public were losing interest. It was enough to have fulfilled the promise of President John F. Kennedy, and to have “beat the Russians.” President Richard Nixon may have paid lip service to bigger and bolder goals when he

As the story is often told, even before the era of manned lunar exploration ended, policymakers and the public were losing interest. It was enough to have fulfilled the promise of President John F. Kennedy, and to have “beat the Russians.” President Richard Nixon may have paid lip service to bigger and bolder goals when he  T

T In his 1987 book Die Schrift, the Czech-born Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser posed the question of whether writing had a future (Hat Schreiben Zukunft? reads Flusser’s subtitle). As he surveyed the media landscape of the late twentieth century, Flusser observed that some aspects of writing (“this ordering of written signs into rows”) could already be “mechanized and automated” thanks to word processing, and he foresaw that artificial intelligence would “surely become more intelligent in the future” allowing the mechanization of writing to proceed further.

In his 1987 book Die Schrift, the Czech-born Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser posed the question of whether writing had a future (Hat Schreiben Zukunft? reads Flusser’s subtitle). As he surveyed the media landscape of the late twentieth century, Flusser observed that some aspects of writing (“this ordering of written signs into rows”) could already be “mechanized and automated” thanks to word processing, and he foresaw that artificial intelligence would “surely become more intelligent in the future” allowing the mechanization of writing to proceed further. Unlike his much more famous colleague Albert Einstein, John von Neumann is not a household name these days, but his discoveries shape the possibilities of life for every creature on this planet. As a teenager, von Neumann provided mathematics with new foundations. He later helped teach the world how to build and detonate nuclear bombs. His invention of game theory furnished the conceptual tools with which superpowers today decide whether to wage war, economists model the behavior of markets, and biologists predict the evolution of viruses. The pioneering programmable computer that von Neumann and his employer, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., completed in 1951 established “von Neumann architecture” as the standard for computer design well into the 21st century, making first IBM and then many other corporations fabulously wealthy.

Unlike his much more famous colleague Albert Einstein, John von Neumann is not a household name these days, but his discoveries shape the possibilities of life for every creature on this planet. As a teenager, von Neumann provided mathematics with new foundations. He later helped teach the world how to build and detonate nuclear bombs. His invention of game theory furnished the conceptual tools with which superpowers today decide whether to wage war, economists model the behavior of markets, and biologists predict the evolution of viruses. The pioneering programmable computer that von Neumann and his employer, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., completed in 1951 established “von Neumann architecture” as the standard for computer design well into the 21st century, making first IBM and then many other corporations fabulously wealthy. For warming to be limited to 1.5 °C, emissions need to fall by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030. According to the

For warming to be limited to 1.5 °C, emissions need to fall by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030. According to the  It’s easy to look at a forest and think it’s inevitable: that the trees came into being through a stately procession of seasons and seeds and soil, and will replenish themselves so long as environmental conditions allow. Hidden from sight are the creatures whose labor makes the forest possible — the multitudes of microorganisms and invertebrates involved in maintaining that soil, and the animals responsible for delivering seeds too heavy to be wind-borne to the places where they will sprout. If one is interested in the future of a forest — which tree species will thrive and which will diminish, or whether those threatened by a fast-changing climate will successfully migrate to newly hospitable lands — one should look to these seed-dispersing animals.

It’s easy to look at a forest and think it’s inevitable: that the trees came into being through a stately procession of seasons and seeds and soil, and will replenish themselves so long as environmental conditions allow. Hidden from sight are the creatures whose labor makes the forest possible — the multitudes of microorganisms and invertebrates involved in maintaining that soil, and the animals responsible for delivering seeds too heavy to be wind-borne to the places where they will sprout. If one is interested in the future of a forest — which tree species will thrive and which will diminish, or whether those threatened by a fast-changing climate will successfully migrate to newly hospitable lands — one should look to these seed-dispersing animals. Donne was not sent to school. He was missing very little; the schools of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were grim, ice cold metaphorically and literally. Eton’s dormitory was full of rats; at many of the public schools at the time, the boys burned the furniture to keep warm, threw each other around in their blankets, broke each other’s ribs and occasionally heads. The Merchant Taylors’ school had in its rules the stipulation, ‘unto their urine the scholars shall go to the places appointed them in the lane or street without the court’, which, assuming the interdiction was necessary for a reason, suggests the school would have smelled strongly of youthful pee. Because smoking was believed to keep the plague at bay, at Eton they were flogged for the crime of not smoking. Discipline could be murderous. It became necessary to enforce startling legal limits: ‘when a schoolmaster, in correcting his scholar, happens to occasion his death, if in such correction he is so barbarous as to exceed all bounds of moderation, he is at least guilty of manslaughter; and if he makes use of an instrument improper for correction, as an iron bar or sword … he is guilty of murder.’

Donne was not sent to school. He was missing very little; the schools of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England were grim, ice cold metaphorically and literally. Eton’s dormitory was full of rats; at many of the public schools at the time, the boys burned the furniture to keep warm, threw each other around in their blankets, broke each other’s ribs and occasionally heads. The Merchant Taylors’ school had in its rules the stipulation, ‘unto their urine the scholars shall go to the places appointed them in the lane or street without the court’, which, assuming the interdiction was necessary for a reason, suggests the school would have smelled strongly of youthful pee. Because smoking was believed to keep the plague at bay, at Eton they were flogged for the crime of not smoking. Discipline could be murderous. It became necessary to enforce startling legal limits: ‘when a schoolmaster, in correcting his scholar, happens to occasion his death, if in such correction he is so barbarous as to exceed all bounds of moderation, he is at least guilty of manslaughter; and if he makes use of an instrument improper for correction, as an iron bar or sword … he is guilty of murder.’ Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh.

Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh.