Linda Kinstler in 1843 Magazine:

In June 2017, Stern, a liberal German magazine, published an article, “Why your banker can save more lives than your doctor”, introducing readers to a social movement called effective altruism. The piece was about a 22-year-old called Carla Zoe Cremer who had grown up in a left-wing family on a farm near Marburg in the west of Germany, where she had taken care of sick horses. The story told of an “old Zoe” and a new one. The old Zoe sold fair-trade coffee and donated the profit to charity. She ran an anti-drug programme at school and believed that small donations and acts of generosity could change lives. The new Zoe was directing her efforts to activities that were, in her view, more effective ways of helping.

In June 2017, Stern, a liberal German magazine, published an article, “Why your banker can save more lives than your doctor”, introducing readers to a social movement called effective altruism. The piece was about a 22-year-old called Carla Zoe Cremer who had grown up in a left-wing family on a farm near Marburg in the west of Germany, where she had taken care of sick horses. The story told of an “old Zoe” and a new one. The old Zoe sold fair-trade coffee and donated the profit to charity. She ran an anti-drug programme at school and believed that small donations and acts of generosity could change lives. The new Zoe was directing her efforts to activities that were, in her view, more effective ways of helping.

Cremer discovered effective altruism through a friend who was at Oxford University. He told her about a community of practical ethicists who claimed to combine “empathy with evidence” in order to “build a better world”. Using mathematics, these effective altruists, or eas as many called themselves, sought to reduce complex ethical choices to a series of cost-benefit equations. Cremer found this philosophy compelling. “It really suited my character at the time to try to think about effectiveness and rigour in everyday life,” she told me. She began attending ea get-togethers in Munich and eventually became a public face of the movement in Germany. Following the guidance of Peter Singer, a philosopher who has inspired many effective altruists, Cremer pledged to donate 10% of her annual income to good causes for the rest of her life, which would make a greater difference than selling coffee beans. As she considered her next job, she was directed towards the movement’s careers arm, 80,000 Hours – a reference to the amount of time that the average person spends at work during their life.

More here.

Will our descendants be cyborgs with hi-tech machine implants, regrowable limbs and cameras for eyes like something out of a science fiction novel? Might humans morph into a hybrid species of biological and artificial beings? Or could we become smaller or taller, thinner or fatter, or even with different facial features and skin colour?

Will our descendants be cyborgs with hi-tech machine implants, regrowable limbs and cameras for eyes like something out of a science fiction novel? Might humans morph into a hybrid species of biological and artificial beings? Or could we become smaller or taller, thinner or fatter, or even with different facial features and skin colour? In 1972, the American artist Lee Bontecou, who died this week at age 91, showed a series of plastic flowers and vacuum-formed fish and sea creatures in New York. She felt she got bad reviews and left the city, settling in rural Pennsylvania, where, with her artist husband, she raised a child (“Having a baby was the most wonderful piece of sculpture I ever made,” she later said). For 20 years she commuted to Brooklyn College to teach, but her low-to-no profile turned her into a kind of ghost artist.

In 1972, the American artist Lee Bontecou, who died this week at age 91, showed a series of plastic flowers and vacuum-formed fish and sea creatures in New York. She felt she got bad reviews and left the city, settling in rural Pennsylvania, where, with her artist husband, she raised a child (“Having a baby was the most wonderful piece of sculpture I ever made,” she later said). For 20 years she commuted to Brooklyn College to teach, but her low-to-no profile turned her into a kind of ghost artist. Enough about the past. We are about to step into Qatar’s balmy winter, average 70 to 79 degrees Fahrenheit, with high humidity to be dispersed by serious AC in the outdoor stadiums. Of the more than two hundred national teams that set out on this journey four years ago, only thirty-two remain, eight groups of four, the top two in each group to move on to the knockout stage. The games will run for almost a month, culminating in a final on December 18.. As is almost always the case, Brazil is favored to win, followed by Argentina, France, England, and Spain, and you never rule out Germany. All these countries have lifted the trophy before, and wouldn’t it be great if someone else crashed the party? After all, Croatia (population 3.8 million) made it to the finals the last time out, and the ageless midfield genius Luka Modrić still runs their show. There is always Kevin De Bruyne’s Belgium (population 11.5 million) or, for a real long shot, Africa’s best hope, Senegal.

Enough about the past. We are about to step into Qatar’s balmy winter, average 70 to 79 degrees Fahrenheit, with high humidity to be dispersed by serious AC in the outdoor stadiums. Of the more than two hundred national teams that set out on this journey four years ago, only thirty-two remain, eight groups of four, the top two in each group to move on to the knockout stage. The games will run for almost a month, culminating in a final on December 18.. As is almost always the case, Brazil is favored to win, followed by Argentina, France, England, and Spain, and you never rule out Germany. All these countries have lifted the trophy before, and wouldn’t it be great if someone else crashed the party? After all, Croatia (population 3.8 million) made it to the finals the last time out, and the ageless midfield genius Luka Modrić still runs their show. There is always Kevin De Bruyne’s Belgium (population 11.5 million) or, for a real long shot, Africa’s best hope, Senegal. In his 1625 essay “Of Truth,” the English writer and politician Francis Bacon—who, a few years earlier, had been deposed from his place as Lord Chancellor of England for corruption—commented on this passage: “What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.” The hint here is that Pilate turns away from Jesus after asking his question because he is afraid it might be answered. And Pilate may not be the only one who has such feelings.

In his 1625 essay “Of Truth,” the English writer and politician Francis Bacon—who, a few years earlier, had been deposed from his place as Lord Chancellor of England for corruption—commented on this passage: “What is truth? said jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.” The hint here is that Pilate turns away from Jesus after asking his question because he is afraid it might be answered. And Pilate may not be the only one who has such feelings. A select group of the world’s top researchers studying obesity

A select group of the world’s top researchers studying obesity  What happened in South Korea offers proof that fundamental transformations of living standards are possible in a few decades. South Korea’s experience, and similar growth trajectories in Taiwan and Singapore, have often been referred to as “economic miracles.” But what if South Korea’s economic growth wasn’t something mysterious or unpredictable, but rather something that we could comprehend and, most importantly, replicate? At current rates of growth, living standards in the poorest countries in the world will eventually catch up to the United States — in about 700 years.

What happened in South Korea offers proof that fundamental transformations of living standards are possible in a few decades. South Korea’s experience, and similar growth trajectories in Taiwan and Singapore, have often been referred to as “economic miracles.” But what if South Korea’s economic growth wasn’t something mysterious or unpredictable, but rather something that we could comprehend and, most importantly, replicate? At current rates of growth, living standards in the poorest countries in the world will eventually catch up to the United States — in about 700 years. Colorado-based Prometheus Materials has developed masonry blocks from a

Colorado-based Prometheus Materials has developed masonry blocks from a  T

T On the first page of his 2015 blockbuster book,

On the first page of his 2015 blockbuster book,  Delegates at the COP27 climate summit in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, have agreed to create a global

Delegates at the COP27 climate summit in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, have agreed to create a global  Barely four decades into its existence, the Islamic republic is confronted by another eruption of public rage, this time brought about by the nation’s women, that may yet end in revolutionary change. A majority of Iranians now groaning under this austere order have no recollection of the revolution that produced it, and reject its central justification—an Islamic concept known as velayat-e faqih, or “guardianship of the jurist.” Originally conceived as a license for the clergy to assume responsibility for orphans and the infirm, the late Ayatollah Khomeini amended it to encompass the whole of society. By these means were his unfortunate subjects relegated to the status of state property.

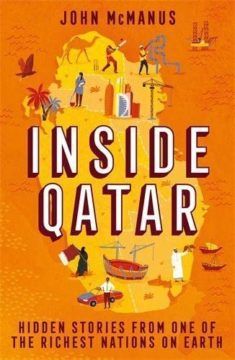

Barely four decades into its existence, the Islamic republic is confronted by another eruption of public rage, this time brought about by the nation’s women, that may yet end in revolutionary change. A majority of Iranians now groaning under this austere order have no recollection of the revolution that produced it, and reject its central justification—an Islamic concept known as velayat-e faqih, or “guardianship of the jurist.” Originally conceived as a license for the clergy to assume responsibility for orphans and the infirm, the late Ayatollah Khomeini amended it to encompass the whole of society. By these means were his unfortunate subjects relegated to the status of state property. Today more than 2.3 million people live in Doha, while Qatar as a whole has a population of 2.9 million, just 300,000 of whom are Qatari citizens. The rest are migrant workers, only a small proportion of whom – Arabic Levantine and Indian families that arrived a generation or two back – have residence rights. Everyone else is there on a temporary work visa: professionals from the Global North; Filipinos, who make up a large proportion of Qatar’s domestic workers and cleaners; Africans, many of whom work as taxi drivers or security guards; and almost a million men from South Asia, Nepal and Bhutan who have toiled to build the new city. This racialised hierarchy, as John McManus argues in his anthropological account of Qatar, is a modern version of the British Empire’s ethnic division of labour.

Today more than 2.3 million people live in Doha, while Qatar as a whole has a population of 2.9 million, just 300,000 of whom are Qatari citizens. The rest are migrant workers, only a small proportion of whom – Arabic Levantine and Indian families that arrived a generation or two back – have residence rights. Everyone else is there on a temporary work visa: professionals from the Global North; Filipinos, who make up a large proportion of Qatar’s domestic workers and cleaners; Africans, many of whom work as taxi drivers or security guards; and almost a million men from South Asia, Nepal and Bhutan who have toiled to build the new city. This racialised hierarchy, as John McManus argues in his anthropological account of Qatar, is a modern version of the British Empire’s ethnic division of labour. In the three-minute short MANGOES (1999) by Berlin-based Pakistani artist Bani Abidi, two women sit next to each other on a white table, each with a mango on a plate in front of them. Both women are played by Abidi. One character has her hair up in a bun, the other loose and flowing down her shoulders. One is Indian, the other Pakistani, both members of the diaspora of an unspecified country. They slice and pull open their respective mangoes, sucking the flesh clean off the skin. The fruit is an oblique symbol of their melancholy and wistful nationalism. As they eat, they speak about the mango-eating traditions of both nation states, but the conversation soon grows strained as they compete over which has more varieties of mango. It’s an arbitrary, quasi-comic tension, but perfectly representative of the sentiments of animosity and hostility that have ruled Indian and Pakistani relations for over seven decades since the Partition of the subcontinent in 1947. Much of Indian/Pakistani difference is mediated and maintained by trivial, and often untrue, distinctions. But it is the myth of this difference that reinforces the border and fuels its continuing clashes. Abidi uses the mango to disturb the border relation: while the Indo-Pak border is a physical site of military presence, surveillance and catastrophe, it is also something a bit more intangible, something conjured and retained in the imagination of those that inhabit it.

In the three-minute short MANGOES (1999) by Berlin-based Pakistani artist Bani Abidi, two women sit next to each other on a white table, each with a mango on a plate in front of them. Both women are played by Abidi. One character has her hair up in a bun, the other loose and flowing down her shoulders. One is Indian, the other Pakistani, both members of the diaspora of an unspecified country. They slice and pull open their respective mangoes, sucking the flesh clean off the skin. The fruit is an oblique symbol of their melancholy and wistful nationalism. As they eat, they speak about the mango-eating traditions of both nation states, but the conversation soon grows strained as they compete over which has more varieties of mango. It’s an arbitrary, quasi-comic tension, but perfectly representative of the sentiments of animosity and hostility that have ruled Indian and Pakistani relations for over seven decades since the Partition of the subcontinent in 1947. Much of Indian/Pakistani difference is mediated and maintained by trivial, and often untrue, distinctions. But it is the myth of this difference that reinforces the border and fuels its continuing clashes. Abidi uses the mango to disturb the border relation: while the Indo-Pak border is a physical site of military presence, surveillance and catastrophe, it is also something a bit more intangible, something conjured and retained in the imagination of those that inhabit it. The Blindest Man follows the story of the elusive Chouette d’Or (or ‘golden owl’)—a golden sculpture buried somewhere in France in 1993 by an author working under the pseudonym of Max Valentin. The same year, Valentin—whose real name was later revealed to be Régis Hauser—released an accompanying book entitled On The Trail of the Golden Owl, which included 11 cryptic clues as to the statuette’s exact location. It became something of a phenomenon in France back then, and almost 30 years later, many people continue to search for it. To this day, however, it remains unfound, and the author has long since passed. Made in France between 2015 and 2018, the pictures in The Blindest Man introduce us to a number of different people on the hunt for the golden owl, following along on their failed routes. These people are referred to as ‘the searchers’.

The Blindest Man follows the story of the elusive Chouette d’Or (or ‘golden owl’)—a golden sculpture buried somewhere in France in 1993 by an author working under the pseudonym of Max Valentin. The same year, Valentin—whose real name was later revealed to be Régis Hauser—released an accompanying book entitled On The Trail of the Golden Owl, which included 11 cryptic clues as to the statuette’s exact location. It became something of a phenomenon in France back then, and almost 30 years later, many people continue to search for it. To this day, however, it remains unfound, and the author has long since passed. Made in France between 2015 and 2018, the pictures in The Blindest Man introduce us to a number of different people on the hunt for the golden owl, following along on their failed routes. These people are referred to as ‘the searchers’.