Rachel Cooke at The Guardian:

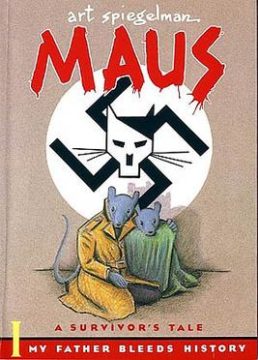

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

more here.

Colette was not merely the most famous writer of her day, but one of the most famous people, period. A demimondaine with a shocking reputation, by the time of

Colette was not merely the most famous writer of her day, but one of the most famous people, period. A demimondaine with a shocking reputation, by the time of  On the last Friday in November, in the afterglow of a literary awards ceremony, the novelist Mieko Kawakami held court in a banquet hall at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, wearing a tweed Gucci dress, clutching an Hermès Birkin handbag and sipping a glass of domestic beer she would never quite finish. Each time she raised the drink to her lips, another writer, editor or publicist came along to distract her from it. Kawakami, who is 46, greeted them each with a degree of warmth that made it hard to tell which were strangers and which were her friends. “I’m a graduate of hostess university,” she said, recalling her years spent working at a bar where she kept men company as they drank. More than two decades later, the skills she honed in the boozy, neon-lit back alleys of Osaka — the ability to observe and to listen with acute curiosity — are still apparent in her best-selling novels. “You can see where that sensitivity arises from in her work,” the translator David Boyd told me. “She sees all the angles.”

On the last Friday in November, in the afterglow of a literary awards ceremony, the novelist Mieko Kawakami held court in a banquet hall at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, wearing a tweed Gucci dress, clutching an Hermès Birkin handbag and sipping a glass of domestic beer she would never quite finish. Each time she raised the drink to her lips, another writer, editor or publicist came along to distract her from it. Kawakami, who is 46, greeted them each with a degree of warmth that made it hard to tell which were strangers and which were her friends. “I’m a graduate of hostess university,” she said, recalling her years spent working at a bar where she kept men company as they drank. More than two decades later, the skills she honed in the boozy, neon-lit back alleys of Osaka — the ability to observe and to listen with acute curiosity — are still apparent in her best-selling novels. “You can see where that sensitivity arises from in her work,” the translator David Boyd told me. “She sees all the angles.” Centered at the Harlem neighborhood in New York City, Harlem Renaissance was an African American movement which peaked around the mid-1920s and during which African Americans took giant strides politically, socially and artistically. Known as the New Negro Movement during the time, it is most closely associated with Jazz and the rise of African American arts. Know more through the 10 most famous people associated with the Harlem Renaissance.

Centered at the Harlem neighborhood in New York City, Harlem Renaissance was an African American movement which peaked around the mid-1920s and during which African Americans took giant strides politically, socially and artistically. Known as the New Negro Movement during the time, it is most closely associated with Jazz and the rise of African American arts. Know more through the 10 most famous people associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Cultivated meat is often heralded as an emerging alternative to intensive animal agriculture, promising new ways to produce slaughter-free beef, pork or poultry proteins. But one cellular ag start-up is working from a different playbook. Primeval Foods is developing lab-grown exotic meats that, it says, can deliver novel food experiences and health benefits.

Cultivated meat is often heralded as an emerging alternative to intensive animal agriculture, promising new ways to produce slaughter-free beef, pork or poultry proteins. But one cellular ag start-up is working from a different playbook. Primeval Foods is developing lab-grown exotic meats that, it says, can deliver novel food experiences and health benefits. Launching a dust cloud from the moon to block sunlight reaching Earth could reduce global warming, but such a strategy may require more than a decade’s worth of research before it can be implemented. The risks involved with such an approach in terms of how it could affect agriculture, ecosystems and water quality in different parts of the world are also unclear.

Launching a dust cloud from the moon to block sunlight reaching Earth could reduce global warming, but such a strategy may require more than a decade’s worth of research before it can be implemented. The risks involved with such an approach in terms of how it could affect agriculture, ecosystems and water quality in different parts of the world are also unclear. As most people know by now, technology is dramatically reshaping the practice of policing. Consider how an investigation might unfold after a spate of shoplifting incidents at a big-box retail store. Authorities believe the same person is responsible for all of them, but they have no leads on the perpetrator’s identity. In a process known as “geofencing,” the police go to a judge and get a warrant instructing Google to use its SensorVault database—which stores location information on any Google users who have “location history” turned on—to provide a list of all cellphones that were within 100 yards of the store in the one-hour range of each day the robberies took place.

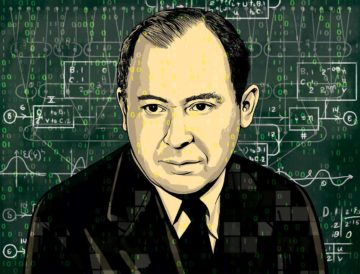

As most people know by now, technology is dramatically reshaping the practice of policing. Consider how an investigation might unfold after a spate of shoplifting incidents at a big-box retail store. Authorities believe the same person is responsible for all of them, but they have no leads on the perpetrator’s identity. In a process known as “geofencing,” the police go to a judge and get a warrant instructing Google to use its SensorVault database—which stores location information on any Google users who have “location history” turned on—to provide a list of all cellphones that were within 100 yards of the store in the one-hour range of each day the robberies took place. The only recipe for surviving technological change, von Neumann concluded, was relying on “human qualities.” But what are those qualities? What is “human” about them? And how can they help us achieve the political forms and ideals necessary to ensure our survival? Von Neumann and his powers of logic did not address those questions. On the contrary, he encouraged us to imagine a strict identity between mathematics and the human, and he gave us the tools to extend one particular kind of human activity—games of strategy—into ever-greater domains of life. Today, game theory and its computational algorithms govern not only our nuclear strategy but also many parts of our working world (Uber, Lyft, and many others), our social lives (Meta, TikTok) and love affairs (Tinder), our access to information (Google), and even our sense of play. Von Neumann’s ideas about human psychology provided the founding charter for the algorithmic “gamification” of the world as we know it. By concealing the distance between logic and the complexity of being rather than minding the gap, his axiomatized “psychology” heightened the very dangers he feared.

The only recipe for surviving technological change, von Neumann concluded, was relying on “human qualities.” But what are those qualities? What is “human” about them? And how can they help us achieve the political forms and ideals necessary to ensure our survival? Von Neumann and his powers of logic did not address those questions. On the contrary, he encouraged us to imagine a strict identity between mathematics and the human, and he gave us the tools to extend one particular kind of human activity—games of strategy—into ever-greater domains of life. Today, game theory and its computational algorithms govern not only our nuclear strategy but also many parts of our working world (Uber, Lyft, and many others), our social lives (Meta, TikTok) and love affairs (Tinder), our access to information (Google), and even our sense of play. Von Neumann’s ideas about human psychology provided the founding charter for the algorithmic “gamification” of the world as we know it. By concealing the distance between logic and the complexity of being rather than minding the gap, his axiomatized “psychology” heightened the very dangers he feared. In

In  The tides of influence in music history move in unexpected ways. There are very few towering rock legends or chart-dominating contemporary rappers, for instance, who’ve enjoyed the sprawling and intensifying authority of the pop-punk band Paramore. The band, which was formed in the mid-two-thousands by a group of Christian teen-agers from the outskirts of Nashville, rose to prominence as emo and pop punk were being commercialized for mainstream audiences. Paramore—fronted by Hayley Williams, a vocal powerhouse with neon-marigold hair and a high degree of emotional athleticism—was a small-town Myspace act that hit it big. By the band’s third album, “Brand New Eyes,” from 2009, it had been nominated for a Grammy and included on the “Twilight” soundtrack. The following year, departing bandmates condemned it for being a “manufactured product of a major label.” No band had ever put the “pop” in “pop punk” more effectively than Paramore.

The tides of influence in music history move in unexpected ways. There are very few towering rock legends or chart-dominating contemporary rappers, for instance, who’ve enjoyed the sprawling and intensifying authority of the pop-punk band Paramore. The band, which was formed in the mid-two-thousands by a group of Christian teen-agers from the outskirts of Nashville, rose to prominence as emo and pop punk were being commercialized for mainstream audiences. Paramore—fronted by Hayley Williams, a vocal powerhouse with neon-marigold hair and a high degree of emotional athleticism—was a small-town Myspace act that hit it big. By the band’s third album, “Brand New Eyes,” from 2009, it had been nominated for a Grammy and included on the “Twilight” soundtrack. The following year, departing bandmates condemned it for being a “manufactured product of a major label.” No band had ever put the “pop” in “pop punk” more effectively than Paramore. African Americans have resisted historic and ongoing oppression, in all forms, especially the racial terrorism of lynching, racial pogroms, and police killings since our arrival upon these shores. These efforts have been to advocate for a dignified self-determined life in a just democratic society in the United States and beyond the United States political jurisdiction. The 1950s and 1970s in the United States was defined by actions such as sit-ins, boycotts, walk outs, strikes by Black people and white allies in the fight for justice against discrimination in all sectors of society from employment to education to housing. Black people have had to consistently push the United States to live up to its ideals of freedom, liberty, and justice for all. Systematic oppression has sought to negate much of the dreams of our griots, like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, and our freedom fighters, like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Septima Clark, and Fannie Lou Hamer fought to realize. Black people have sought ways to nurture and protect Black lives, and for autonomy of their physical and intellectual bodies through armed resistance, voluntary emigration, nonviolence, education, literature, sports, media, and legislation/politics. Black led institutions and affiliations have lobbied, litigated, legislated, protested, and achieved success.

African Americans have resisted historic and ongoing oppression, in all forms, especially the racial terrorism of lynching, racial pogroms, and police killings since our arrival upon these shores. These efforts have been to advocate for a dignified self-determined life in a just democratic society in the United States and beyond the United States political jurisdiction. The 1950s and 1970s in the United States was defined by actions such as sit-ins, boycotts, walk outs, strikes by Black people and white allies in the fight for justice against discrimination in all sectors of society from employment to education to housing. Black people have had to consistently push the United States to live up to its ideals of freedom, liberty, and justice for all. Systematic oppression has sought to negate much of the dreams of our griots, like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, and our freedom fighters, like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Septima Clark, and Fannie Lou Hamer fought to realize. Black people have sought ways to nurture and protect Black lives, and for autonomy of their physical and intellectual bodies through armed resistance, voluntary emigration, nonviolence, education, literature, sports, media, and legislation/politics. Black led institutions and affiliations have lobbied, litigated, legislated, protested, and achieved success. Music looms as a spectral presence over Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Blue, White, and Red, collectively known as the Three Colors trilogy. Like the triad of colored lights that bounce on the beautiful, sad faces in the films, Zbigniew Preisner’s multi-hued scores reflect on the images and refract from the inside out. Stern, lonely, and at times almost unbearably passionate, they often penetrate the ears and hearts of the characters. When the grieving heroine of Blue is suddenly overwhelmed by notes from a stoic oratorio, those notes are Preisner’s; when the lost protagonist of Red finds solace in an aria she plays at a record store, the music flowing through her headphones is his. Kieślowski may have written the stories—with the help of screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz and screenplay consultants Agnieszka Holland, Edward Zebrowski, Slawomir Idziak, Edward Kłosiński, and Piotr Sobociński—but Preisner deserves credit for cocreating the trilogy’s mood of existential despair.

Music looms as a spectral presence over Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Blue, White, and Red, collectively known as the Three Colors trilogy. Like the triad of colored lights that bounce on the beautiful, sad faces in the films, Zbigniew Preisner’s multi-hued scores reflect on the images and refract from the inside out. Stern, lonely, and at times almost unbearably passionate, they often penetrate the ears and hearts of the characters. When the grieving heroine of Blue is suddenly overwhelmed by notes from a stoic oratorio, those notes are Preisner’s; when the lost protagonist of Red finds solace in an aria she plays at a record store, the music flowing through her headphones is his. Kieślowski may have written the stories—with the help of screenwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz and screenplay consultants Agnieszka Holland, Edward Zebrowski, Slawomir Idziak, Edward Kłosiński, and Piotr Sobociński—but Preisner deserves credit for cocreating the trilogy’s mood of existential despair. In 1948, Albert Camus gave a speech at a Dominican monastery. The invitation was unusual. At this time, Camus’s best-known novel was The Stranger (1). He was often called “the philosopher of the absurd” because his philosophical essay, The Myth of Sisyphus (2), grappled with the question: why should you not kill yourself, given that the universe is without a purpose? And yet, these Dominicans asked Camus to speak on the theme of what the atheist would ask of the theist.

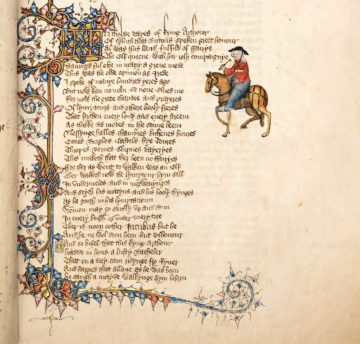

In 1948, Albert Camus gave a speech at a Dominican monastery. The invitation was unusual. At this time, Camus’s best-known novel was The Stranger (1). He was often called “the philosopher of the absurd” because his philosophical essay, The Myth of Sisyphus (2), grappled with the question: why should you not kill yourself, given that the universe is without a purpose? And yet, these Dominicans asked Camus to speak on the theme of what the atheist would ask of the theist. The Wife of Bath is the first ordinary woman in English literature. By that I mean the first mercantile, working, sexually active woman—not a virginal princess or queen, not a nun, witch, or sorceress, not a damsel in distress nor a functional servant character, not an allegory. A much married woman and widow, who works in the cloth trade and tells us about her friends, her tricks, her experience of domestic abuse, her long career combating misogyny, her reflections on the aging process, and her enjoyment of sex, Alison exudes vitality, wit, and rebellious self-confidence.

The Wife of Bath is the first ordinary woman in English literature. By that I mean the first mercantile, working, sexually active woman—not a virginal princess or queen, not a nun, witch, or sorceress, not a damsel in distress nor a functional servant character, not an allegory. A much married woman and widow, who works in the cloth trade and tells us about her friends, her tricks, her experience of domestic abuse, her long career combating misogyny, her reflections on the aging process, and her enjoyment of sex, Alison exudes vitality, wit, and rebellious self-confidence.