Chris Impey and Connie Walker in The Conversation:

For most of human history, the stars blazed in an otherwise dark night sky. But starting around the Industrial Revolution, as artificial light increasingly lit cities and towns at night, the stars began to disappear.

For most of human history, the stars blazed in an otherwise dark night sky. But starting around the Industrial Revolution, as artificial light increasingly lit cities and towns at night, the stars began to disappear.

We are two astronomers who depend on dark night skies to do our research. For decades, astronomers have been building telescopes in the darkest places on Earth to avoid light pollution.

Today, most people live in cities or suburbs that needlessly shine light into the sky at night, dramatically reducing the visibility of stars. Satellite data suggests that light pollution over North America and Europe has remained constant or has slightly decreased over the last decade, while increasing in other parts of the world, such as Africa, Asia and South America. However, satellites miss the blue light of LEDs, which are commonly used for outdoor lighting – resulting in an underestimate of light pollution.

An international citizen science project called Globe at Night aims to measure how everyday people’s view of the sky is changing.

More here.

I often watch the television show “Hoarders.” One of my favorite episodes features the pack rats Patty and Debra. Patty is a typical trash-and-filth hoarder: her bathroom contains horrors I’d rather not describe, and her story follows the show’s typical arc of reform and redemption. But Debra, who hoards clothes, home decorations, and tchotchkes, is more unusual. She doesn’t believe that she has a problem; in fact, she’s completely unimpressed by the producers’ efforts to fix her house. “It’s just not my color, white,” she says, walking through her newly de-hoarded rooms. “Everything that I really loved in my house is gone.” She is unrepentant, concluding, “This is horrible—I hate it!” Debra just loves to hoard, and people who want her to stop don’t get it.

I often watch the television show “Hoarders.” One of my favorite episodes features the pack rats Patty and Debra. Patty is a typical trash-and-filth hoarder: her bathroom contains horrors I’d rather not describe, and her story follows the show’s typical arc of reform and redemption. But Debra, who hoards clothes, home decorations, and tchotchkes, is more unusual. She doesn’t believe that she has a problem; in fact, she’s completely unimpressed by the producers’ efforts to fix her house. “It’s just not my color, white,” she says, walking through her newly de-hoarded rooms. “Everything that I really loved in my house is gone.” She is unrepentant, concluding, “This is horrible—I hate it!” Debra just loves to hoard, and people who want her to stop don’t get it. The defining feature of our world is life. For all we know, Earth is the only planet with life on it. Despite our age of environmental destruction, there’s life in every corner of the globe, under its water, nestled in the most extreme environments we can imagine. But why? How did life start on Earth? What was the series of events that led to birds, bugs, amoebas, you, and me? That’s the subject of Origins, a three-episode series from

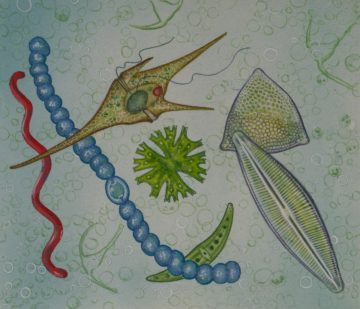

The defining feature of our world is life. For all we know, Earth is the only planet with life on it. Despite our age of environmental destruction, there’s life in every corner of the globe, under its water, nestled in the most extreme environments we can imagine. But why? How did life start on Earth? What was the series of events that led to birds, bugs, amoebas, you, and me? That’s the subject of Origins, a three-episode series from  Emotions such as fear and

Emotions such as fear and  What is the matter with theory? More specifically, what does a distinctively modern approach to theorizing have to do with the prevalence of the kind of conspiracist thinking that thrives in our era of post-truth politics? To find answers to that question, political and cultural analysts have recently returned to the work of Hannah Arendt—and for good reason. Despite her training as a philosopher in her native Germany, the brilliant Jewish émigré thinker (1906–75) was not only not a theorist but even something of an anti-theorist, a practitioner of exercises of political thinking that were never theoretical in the usual sense. Ranging from her magisterial Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition to her many essays, reviews, and works of analytical reportage (notably in Eichmann in Jerusalem), her oeuvre might best be characterized as a form of praxis, of thought in action. Grounded in the common world, this form of political thinking aims to support continued and active engagement in that world.

What is the matter with theory? More specifically, what does a distinctively modern approach to theorizing have to do with the prevalence of the kind of conspiracist thinking that thrives in our era of post-truth politics? To find answers to that question, political and cultural analysts have recently returned to the work of Hannah Arendt—and for good reason. Despite her training as a philosopher in her native Germany, the brilliant Jewish émigré thinker (1906–75) was not only not a theorist but even something of an anti-theorist, a practitioner of exercises of political thinking that were never theoretical in the usual sense. Ranging from her magisterial Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition to her many essays, reviews, and works of analytical reportage (notably in Eichmann in Jerusalem), her oeuvre might best be characterized as a form of praxis, of thought in action. Grounded in the common world, this form of political thinking aims to support continued and active engagement in that world. Why did I want a Californian? Well, that was not exactly what I wrote, although I appreciated the headline writer’s teasing provocation. What I did write was that the next pope should be “a bit of a Californian.” I opened the piece by quoting the novelist Walker Percy’s cantankerous assertion that Catholics had to choose between “either Rome or California.” In Percy’s mind, California stood for everything alienating, dehumanizing, and spiritually moribund in modern life, while Roman Catholicism offered the true, if demanding, path to human flourishing. I thought that was a false choice. The Church would have to come to terms with everything California represented; retreating from the modern world was not an option. “Rome is no refuge; it never has been, and as recent scandals remind us, never could be,” I wrote. “Yet Rome has much missionary work to do—in California and elsewhere. That work will require a change in tone and a refusal to condemn what it cannot yet understand.” In conclusion, I quoted the philosopher Charles Taylor. Rome proposes “too many answers choking off questions and too little sense of the enigmas that accompany a life of faith; these are what stop a conversation from ever starting between our Church and much of our world.”

Why did I want a Californian? Well, that was not exactly what I wrote, although I appreciated the headline writer’s teasing provocation. What I did write was that the next pope should be “a bit of a Californian.” I opened the piece by quoting the novelist Walker Percy’s cantankerous assertion that Catholics had to choose between “either Rome or California.” In Percy’s mind, California stood for everything alienating, dehumanizing, and spiritually moribund in modern life, while Roman Catholicism offered the true, if demanding, path to human flourishing. I thought that was a false choice. The Church would have to come to terms with everything California represented; retreating from the modern world was not an option. “Rome is no refuge; it never has been, and as recent scandals remind us, never could be,” I wrote. “Yet Rome has much missionary work to do—in California and elsewhere. That work will require a change in tone and a refusal to condemn what it cannot yet understand.” In conclusion, I quoted the philosopher Charles Taylor. Rome proposes “too many answers choking off questions and too little sense of the enigmas that accompany a life of faith; these are what stop a conversation from ever starting between our Church and much of our world.” Last week,

Last week,  Viruses are notorious as scourges of cellular life, destroying as ruthlessly as any predator. Yet as microbiologists are now piecing together, these killers also sometimes perish as prey.

Viruses are notorious as scourges of cellular life, destroying as ruthlessly as any predator. Yet as microbiologists are now piecing together, these killers also sometimes perish as prey. Riley Moore: It’s difficult to discuss Aristotle without discussing everything, because Aristotle wrote about everything—ethics, logic, biology, politics, literature; anything knowable, he investigated it. You go through this in detail in your newest book, Aristotle: Understanding the World’s Greatest Philosopher. Let’s pretend I have never heard of Aristotle. Who was Aristotle, biographically? Was he a pupil of Plato just as Plato was a pupil of Socrates? Is there a direct lineage there?

Riley Moore: It’s difficult to discuss Aristotle without discussing everything, because Aristotle wrote about everything—ethics, logic, biology, politics, literature; anything knowable, he investigated it. You go through this in detail in your newest book, Aristotle: Understanding the World’s Greatest Philosopher. Let’s pretend I have never heard of Aristotle. Who was Aristotle, biographically? Was he a pupil of Plato just as Plato was a pupil of Socrates? Is there a direct lineage there? W

W Billions of years ago, before there were beasts, bacteria or any living organism, there were RNAs. These molecules were probably swirling around with amino acids and other rudimentary biomolecules, merging and diverging, on an otherwise lifeless crucible of a planet.

Billions of years ago, before there were beasts, bacteria or any living organism, there were RNAs. These molecules were probably swirling around with amino acids and other rudimentary biomolecules, merging and diverging, on an otherwise lifeless crucible of a planet. According to a familiar story, science was born as a pastime of seventeenth-century European gentlemen, who built air pumps, traded telescopes, and measured everything from the size of the earth to the eye of a fly as they sought to uncover the laws of nature. Through careful experimentation and observation of nature, these men—who called themselves natural philosophers—distinguished themselves from the scholastic schoolmen of yore, who had instead busied themselves with writing commentary upon commentary on Aristotle and Aquinas. They also wrote about themselves. They formed societies, took notes at their meetings, compiled their notes into journals, and penned books recording their achievements; it was a mere seven years after the founding of the Royal Society in 1660 that Thomas Sprat published its first history. Reason had finally come into its own, and it arrived with a diligent group of stenographers.

According to a familiar story, science was born as a pastime of seventeenth-century European gentlemen, who built air pumps, traded telescopes, and measured everything from the size of the earth to the eye of a fly as they sought to uncover the laws of nature. Through careful experimentation and observation of nature, these men—who called themselves natural philosophers—distinguished themselves from the scholastic schoolmen of yore, who had instead busied themselves with writing commentary upon commentary on Aristotle and Aquinas. They also wrote about themselves. They formed societies, took notes at their meetings, compiled their notes into journals, and penned books recording their achievements; it was a mere seven years after the founding of the Royal Society in 1660 that Thomas Sprat published its first history. Reason had finally come into its own, and it arrived with a diligent group of stenographers. To successfully navigate their world, organisms rely on numerous senses. Birds are no exception to this; and yet, for a long time, people have been convinced that birds cannot smell. This came as a surprise to evolutionary biologist Danielle J. Whittaker. Given that smell is effectively chemoreception (the sensing of chemical gradients in your environment) and was

To successfully navigate their world, organisms rely on numerous senses. Birds are no exception to this; and yet, for a long time, people have been convinced that birds cannot smell. This came as a surprise to evolutionary biologist Danielle J. Whittaker. Given that smell is effectively chemoreception (the sensing of chemical gradients in your environment) and was  At turns hilariously absurd and gut-wrenchingly heartfelt, Terese Svoboda’s Dog on Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press, defies genre. Svoboda juggles comedy, mystery, tragedy, horror—and masters them all. The book follows a recently-divorced woman grieving the mysterious and early death of her estranged brother. Her unusual circumstances lead her to move back to her small Midwestern home town, where everything and anything she does creates ripples of rumor. There, she confronts perilous Halloween parties, Jell-O inventions, guns, grave-diggers, and, of course, dogs on fire.

At turns hilariously absurd and gut-wrenchingly heartfelt, Terese Svoboda’s Dog on Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press, defies genre. Svoboda juggles comedy, mystery, tragedy, horror—and masters them all. The book follows a recently-divorced woman grieving the mysterious and early death of her estranged brother. Her unusual circumstances lead her to move back to her small Midwestern home town, where everything and anything she does creates ripples of rumor. There, she confronts perilous Halloween parties, Jell-O inventions, guns, grave-diggers, and, of course, dogs on fire. G

G