Rana Dasgupta in The Yale Review:

During these first nine months of Trump’s second presidency, the question of his personal psychology has dominated the media to a level unprecedented in American political analysis. His need for flattery, his vindictiveness, his compulsion to lie, his worship of money, his misogyny—only through such intimacies, apparently, can we understand the policies of the capitalist superpower under its forty-seventh president.

During these first nine months of Trump’s second presidency, the question of his personal psychology has dominated the media to a level unprecedented in American political analysis. His need for flattery, his vindictiveness, his compulsion to lie, his worship of money, his misogyny—only through such intimacies, apparently, can we understand the policies of the capitalist superpower under its forty-seventh president.

It is easy to see where the obsession with personality comes from. Since Trump makes such extensive use of the executive order and ignores institutional custom, there is little to constrain his psyche, which therefore, the argument goes, becomes the central political question. But it is too convenient to imagine that America’s present upheaval springs from one man’s head. It is also the result of a deeper process, of which Trump is merely a symptom: the ongoing transformation of the American state.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

UFOs exist. On that we can all agree. The question is not whether they are but what they are.

UFOs exist. On that we can all agree. The question is not whether they are but what they are. Brakhage virtually invented and singularly dominated the characteristic genre of American avant-garde cinema: the crisis film, that lyric articulation of the moods and observations of the filmmaker, following a rhythmical association of images without a predetermined scenario or enacted drama. Since the early ’60s he handpainted on film so elaborately that he brought that way of filmmaking, at least as old as Len Lye’s work in the mid-’30s, to new profundities. It became the predominant process of his filmmaking in the ’90s. Perhaps a quarter of his oeuvre was made without using a camera.

Brakhage virtually invented and singularly dominated the characteristic genre of American avant-garde cinema: the crisis film, that lyric articulation of the moods and observations of the filmmaker, following a rhythmical association of images without a predetermined scenario or enacted drama. Since the early ’60s he handpainted on film so elaborately that he brought that way of filmmaking, at least as old as Len Lye’s work in the mid-’30s, to new profundities. It became the predominant process of his filmmaking in the ’90s. Perhaps a quarter of his oeuvre was made without using a camera. I looked at my wife. Her eyes — soulful, brown, impossibly beautiful — met mine. I had looked into them thousands of times before, but in that moment, I wondered: Had I ever really seen them?

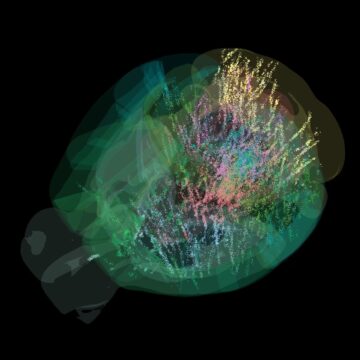

I looked at my wife. Her eyes — soulful, brown, impossibly beautiful — met mine. I had looked into them thousands of times before, but in that moment, I wondered: Had I ever really seen them? Neuroscientists from 22 labs joined forces in an unprecedented international partnership to produce a landmark achievement: a neural map that shows activity across the entire brain during decision-making.

Neuroscientists from 22 labs joined forces in an unprecedented international partnership to produce a landmark achievement: a neural map that shows activity across the entire brain during decision-making. Polycrisis is a descriptor that the establishment can agree on without challenging itself. It abstracts the causes of crises, making them appear as natural convergences rather than the systemic outcomes of extractive and exclusionary orders. And it makes the concept appear global when in fact the voices, experiences, and priorities it reflects are overwhelmingly Eurocentric.

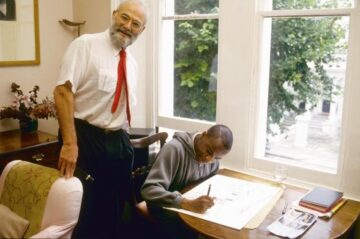

Polycrisis is a descriptor that the establishment can agree on without challenging itself. It abstracts the causes of crises, making them appear as natural convergences rather than the systemic outcomes of extractive and exclusionary orders. And it makes the concept appear global when in fact the voices, experiences, and priorities it reflects are overwhelmingly Eurocentric. To think today of the late Oliver Sacks, physician and author, is to bring to mind the extraordinary fellow human beings whose defects and gifts, depicted in Sacks’s books and essays, made the world a bit larger and much more interesting: the twin autistic boys who could instantly recall hundred-digit figures; the man who could not identify the person at whom he was staring in the mirror; the sailor for whom the distant past was detailed and vividly clear but for whom the immediate past had no existence; the woman without an awareness that she had been enclosed for sixty years in a body, her own; and, of course, the scores of victims of the 1920s encephalitis epidemic who had been treated with the new L-DOPA drug, and had recovered for a brief period the awareness of living. All these human exceptions peopled the world of medicine that Sacks created for his readers.

To think today of the late Oliver Sacks, physician and author, is to bring to mind the extraordinary fellow human beings whose defects and gifts, depicted in Sacks’s books and essays, made the world a bit larger and much more interesting: the twin autistic boys who could instantly recall hundred-digit figures; the man who could not identify the person at whom he was staring in the mirror; the sailor for whom the distant past was detailed and vividly clear but for whom the immediate past had no existence; the woman without an awareness that she had been enclosed for sixty years in a body, her own; and, of course, the scores of victims of the 1920s encephalitis epidemic who had been treated with the new L-DOPA drug, and had recovered for a brief period the awareness of living. All these human exceptions peopled the world of medicine that Sacks created for his readers. ADHD exists in this odd diagnostic liminal space where we know it’s a thing, but it’s hard to definitively pinpoint it in the physical structures of the brain. MRI studies have given us mixed signals over the years. Some say kids with smaller gray matter volumes in their brains are more likely to

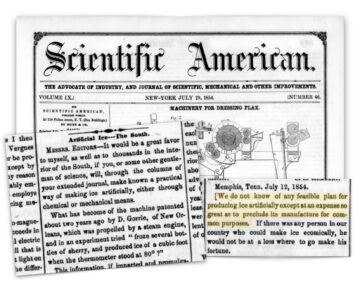

ADHD exists in this odd diagnostic liminal space where we know it’s a thing, but it’s hard to definitively pinpoint it in the physical structures of the brain. MRI studies have given us mixed signals over the years. Some say kids with smaller gray matter volumes in their brains are more likely to  Artificial meat is under attack: US states like Montana, Mississippi and Alabama have banned it – taking the lead from

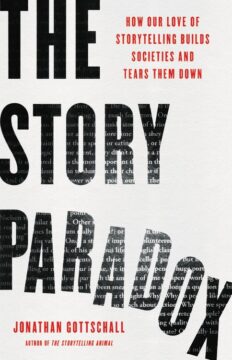

Artificial meat is under attack: US states like Montana, Mississippi and Alabama have banned it – taking the lead from  I just read the above-titled book by Jonathan Gottschall. It was really interesting–he convincingly argues that (a) stories are a central part of lives and always will be, and (b) stories are dangerous and we’re living in a world of dangerous stories. The book isn’t perfect–the author is a bit too credulous for my taste in citing dubious social-psychology studies–but no book is perfect, and I got a lot out of it, and now that I’ve read it, I feel pretty much in agreement with its arguments.

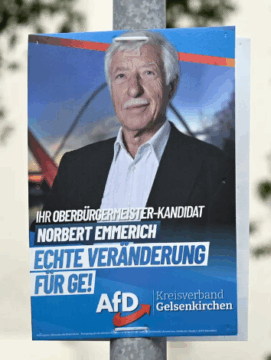

I just read the above-titled book by Jonathan Gottschall. It was really interesting–he convincingly argues that (a) stories are a central part of lives and always will be, and (b) stories are dangerous and we’re living in a world of dangerous stories. The book isn’t perfect–the author is a bit too credulous for my taste in citing dubious social-psychology studies–but no book is perfect, and I got a lot out of it, and now that I’ve read it, I feel pretty much in agreement with its arguments. Almost all theories in elite discourse about why people vote for right-wing populism posit that deindustrialization or free trade or “neoliberalism” or some other thing that left-wing intellectuals think is bad induces support for political parties on the right.

Almost all theories in elite discourse about why people vote for right-wing populism posit that deindustrialization or free trade or “neoliberalism” or some other thing that left-wing intellectuals think is bad induces support for political parties on the right. Carlisle illustrates the difference with a children’s fable told in Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa. In brief: a man stumbles around in the mud for a while in the middle of the night. He loses his way, changes direction and trips over a few things before going back to bed. Only when he wakes up and sees the scene by daylight does he realise that his footprints have traced out a perfect picture of a stork. The point is that, by living, we create a meaningful picture without knowing it – unless we attain some inkling of that wider view through art or mysticism.

Carlisle illustrates the difference with a children’s fable told in Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa. In brief: a man stumbles around in the mud for a while in the middle of the night. He loses his way, changes direction and trips over a few things before going back to bed. Only when he wakes up and sees the scene by daylight does he realise that his footprints have traced out a perfect picture of a stork. The point is that, by living, we create a meaningful picture without knowing it – unless we attain some inkling of that wider view through art or mysticism. Growing up, one of the first things I learned from the Bible was the commandment Thou shalt not kill. This makes sense considering that the religious community I belong to—the Bruderhof—is rooted in Anabaptism, a Christian tradition that, with occasional exceptions, has been pacifist since 1525. (The Anabaptist movement, which also includes the Amish, Mennonites and Hutterites, celebrates its quincentenary this year.) Over the sixteenth century, thousands of Anabaptists were executed as traitors to Christendom by Catholic and Protestant rulers. No doubt that’s why their signature virtue was Gelassenheit—“self-abandonment,” “submission,” “readiness to suffer.” It’s an ethic Nietzsche would have hated.

Growing up, one of the first things I learned from the Bible was the commandment Thou shalt not kill. This makes sense considering that the religious community I belong to—the Bruderhof—is rooted in Anabaptism, a Christian tradition that, with occasional exceptions, has been pacifist since 1525. (The Anabaptist movement, which also includes the Amish, Mennonites and Hutterites, celebrates its quincentenary this year.) Over the sixteenth century, thousands of Anabaptists were executed as traitors to Christendom by Catholic and Protestant rulers. No doubt that’s why their signature virtue was Gelassenheit—“self-abandonment,” “submission,” “readiness to suffer.” It’s an ethic Nietzsche would have hated.