Mariella Careaga in The Scientist:

Remembering what happened to us is more than just looking back to the past. The memories our brains store and later recall affect who we are, how we behave, and how we connect with others. Morgan Barense, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Toronto, believes in that.

Remembering what happened to us is more than just looking back to the past. The memories our brains store and later recall affect who we are, how we behave, and how we connect with others. Morgan Barense, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Toronto, believes in that.

As people age, it becomes harder to remember specific details of past experiences, and the loss of vividness in people’s memories significantly worsens their qualities of life (1). “When you start to lose your memory for the past, that can be really disorienting because you feel disconnected, not only from the things that you’ve done, but who you are as a person,” said Barense. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a group of researchers led by Barense showed that a mobile memory intervention they developed helped older adults preserve detail rich memories. They also provided evidence of the patterns of brain activity in the hippocampus associated with that memory enhancement (2).

More here.

Aristotle called the hand the “tool of tools”; Kant, “the visible part of the brain.” The earliest works of art were handprints on the walls of caves. Throughout history hand gestures have symbolized the range of human experience: power, tenderness, creativity, conflict, even (bravo, Michelangelo) the touch of the divine. Without hands, civilization would be inconceivable. And so the discovery in 2011 of the bones of a dozen right hands, at a site where the ancient Egyptian city of Avaris (today known as Tell el-Dab’a) once stood, was particularly unsettling. The remains were unearthed, most with palms down, from three shallow pits near the throne room of a royal palace. The hands, along with numerous disarticulated fingers, were most likely buried during Egypt’s 15th dynasty, from 1640 B.C. to 1530 B.C. At the time, Egypt’s eastern Nile Delta was controlled by a dynasty called the Hyksos, which means “rulers of foreign countries.”

Aristotle called the hand the “tool of tools”; Kant, “the visible part of the brain.” The earliest works of art were handprints on the walls of caves. Throughout history hand gestures have symbolized the range of human experience: power, tenderness, creativity, conflict, even (bravo, Michelangelo) the touch of the divine. Without hands, civilization would be inconceivable. And so the discovery in 2011 of the bones of a dozen right hands, at a site where the ancient Egyptian city of Avaris (today known as Tell el-Dab’a) once stood, was particularly unsettling. The remains were unearthed, most with palms down, from three shallow pits near the throne room of a royal palace. The hands, along with numerous disarticulated fingers, were most likely buried during Egypt’s 15th dynasty, from 1640 B.C. to 1530 B.C. At the time, Egypt’s eastern Nile Delta was controlled by a dynasty called the Hyksos, which means “rulers of foreign countries.” THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT VIDEO ART that calls for grand theories and epic summations, wild pronouncements and heroic declarations. It’s exciting to see a new technology appear in one’s lifetime and to feel some kind of ownership over it, to see it for what it is or, even more importantly, what it did—how it cut through the world. And since video is, or was, so closely related to television and what used to be called the mass media—it was either its intimate underbelly or a guerrilla weapon made to combat it—its value seemed to go unquestioned. The most important artists wrestled with it (Lynda Benglis, Dara Birnbaum, Nam June Paik, Ulysses Jenkins, Joan Jonas, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson); some of the best writers took it on (David Antin, Allan Kaprow, Rosalind Krauss, Anne Wagner). But when television went from a weekly calendar to a massive database that viewers could scan wherever, whenever, something changed; as video’s hardware flattened out and flooded the world, grafting itself onto automobiles and gas pumps—not to mention phones, bus stops, and airplanes—something gave way. (“In the mid-nineteen sixties people started moving television sets away from the wall,” Gregory Battcock wrote long ago. “The implications of this phenomenon . . . are enormous.”) It was as if every surface in the world had suddenly come throbbingly, pulsingly alive. Production also transformed. If the shift from film camera to Porta-Pak cut down on crew, the leap to phone and personal computer offered advanced editing techniques to almost any amateur—so video changed not only the world’s texture but also how we interact with it.

THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT VIDEO ART that calls for grand theories and epic summations, wild pronouncements and heroic declarations. It’s exciting to see a new technology appear in one’s lifetime and to feel some kind of ownership over it, to see it for what it is or, even more importantly, what it did—how it cut through the world. And since video is, or was, so closely related to television and what used to be called the mass media—it was either its intimate underbelly or a guerrilla weapon made to combat it—its value seemed to go unquestioned. The most important artists wrestled with it (Lynda Benglis, Dara Birnbaum, Nam June Paik, Ulysses Jenkins, Joan Jonas, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson); some of the best writers took it on (David Antin, Allan Kaprow, Rosalind Krauss, Anne Wagner). But when television went from a weekly calendar to a massive database that viewers could scan wherever, whenever, something changed; as video’s hardware flattened out and flooded the world, grafting itself onto automobiles and gas pumps—not to mention phones, bus stops, and airplanes—something gave way. (“In the mid-nineteen sixties people started moving television sets away from the wall,” Gregory Battcock wrote long ago. “The implications of this phenomenon . . . are enormous.”) It was as if every surface in the world had suddenly come throbbingly, pulsingly alive. Production also transformed. If the shift from film camera to Porta-Pak cut down on crew, the leap to phone and personal computer offered advanced editing techniques to almost any amateur—so video changed not only the world’s texture but also how we interact with it. All that you touch / All that you see. The English graphic designer Storm Thorgerson, speaking of his career’s most iconic album cover, told the BBC in 2009: “Refracting light through a prism is a common feature in nature, as in a rainbow. I would like to claim it, but unfortunately it’s not mine!” In its title and in the color prism now eternally associated with it, The Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd’s 1973 magnum opus, elides the distinction between two very distinct chapters in the history of science. One is Isaac Newton’s discovery, spelled out in the 1704 Opticks, that the prism does not so much produce color from light as it separates out the colors that are already in light. If refraction is a common occurrence in nature, nonetheless for 269 years, until Thorgerson’s appropriation of it, the image of the prism belonged to the Newtonian legacy. The other chapter, the history of that side of the earth’s sole natural satellite that, as a result of so-called “tidal locking,” remains in its orbit perpetually occluded from terrestrial view, is rather more difficult to trace back through all of its pre-Floydian instances.

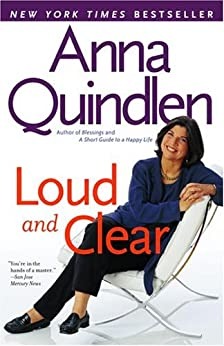

All that you touch / All that you see. The English graphic designer Storm Thorgerson, speaking of his career’s most iconic album cover, told the BBC in 2009: “Refracting light through a prism is a common feature in nature, as in a rainbow. I would like to claim it, but unfortunately it’s not mine!” In its title and in the color prism now eternally associated with it, The Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd’s 1973 magnum opus, elides the distinction between two very distinct chapters in the history of science. One is Isaac Newton’s discovery, spelled out in the 1704 Opticks, that the prism does not so much produce color from light as it separates out the colors that are already in light. If refraction is a common occurrence in nature, nonetheless for 269 years, until Thorgerson’s appropriation of it, the image of the prism belonged to the Newtonian legacy. The other chapter, the history of that side of the earth’s sole natural satellite that, as a result of so-called “tidal locking,” remains in its orbit perpetually occluded from terrestrial view, is rather more difficult to trace back through all of its pre-Floydian instances. In all her work, Biss scrutinizes the nature of our connection in American life. In one of her early essays, “Time and Distance Overcome,” she looks at how telephone poles, instruments of communication, became gallows in public lynchings across the country in the early twentieth century. Vaccines—our greatest collective defense against viral disease—become a symbol of violation and trespass. Money, our shared concrete metaphor of value, becomes a tool of exclusion. Each subject Biss examines exposes the contested ground on which we make and remake our American identities.

In all her work, Biss scrutinizes the nature of our connection in American life. In one of her early essays, “Time and Distance Overcome,” she looks at how telephone poles, instruments of communication, became gallows in public lynchings across the country in the early twentieth century. Vaccines—our greatest collective defense against viral disease—become a symbol of violation and trespass. Money, our shared concrete metaphor of value, becomes a tool of exclusion. Each subject Biss examines exposes the contested ground on which we make and remake our American identities. Forty years ago, Frank Wilczek was mulling over a bizarre type of particle that could live only in a flat universe. Had he put pen to paper and done the calculations, Wilczek would have found that these then-theoretical particles held an otherworldly memory of their past, one woven too thoroughly into the fabric of reality for any one disturbance to erase it.

Forty years ago, Frank Wilczek was mulling over a bizarre type of particle that could live only in a flat universe. Had he put pen to paper and done the calculations, Wilczek would have found that these then-theoretical particles held an otherworldly memory of their past, one woven too thoroughly into the fabric of reality for any one disturbance to erase it. Bruno Schulz is an author who never tires of being discovered. A writer and artist whose known corpus includes two slim collections of stories, a bundle of letters, and a handful of visual works, mostly drawings. Schulz was born in 1892 in Drohobycz, a small Galician town that was then under Austro-Hungarian rule. He died in that same town in 1942, shot in the head by a Nazi officer. His life and work would likely have been unknown but for the efforts of a handful of people for whom his work meant the world.

Bruno Schulz is an author who never tires of being discovered. A writer and artist whose known corpus includes two slim collections of stories, a bundle of letters, and a handful of visual works, mostly drawings. Schulz was born in 1892 in Drohobycz, a small Galician town that was then under Austro-Hungarian rule. He died in that same town in 1942, shot in the head by a Nazi officer. His life and work would likely have been unknown but for the efforts of a handful of people for whom his work meant the world. The race to roll out

The race to roll out  A friend of mine used to joke that women writers discovered friendship in 2015, when the last volume of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet came out. I laughed, but I knew what he meant. It is easy to think of men who navigated the literary world together: Jonson and Shakespeare, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Johnson and Boswell, Shelley and Byron, Marx and Engels, Sartre and Camus, Bellow and Roth, Hughes and Heaney, Amis and Barnes. In Weimar for a day in summer 2014, bitter laughter rose in me when I emerged into Theaterplatz to find a monument to literary bro-dom: Goethe and Schiller in bronze, each with a hand on a shared crown of laurels. With stout folds in Goethe’s breeches and pupils missing from Schiller’s eyes, the unlovely statue had been cast in 1857, twenty-five years after Goethe died, and had stood for more than a century facing the stage where Goethe had directed many of Schiller’s plays. In the early twentieth century, copies of the monument were made for San Francisco, Cleveland, Milwaukee and Syracuse and erected in parks in those cities. I laughed some more when I found that out. Is there such a thing as jealous laughter?

A friend of mine used to joke that women writers discovered friendship in 2015, when the last volume of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet came out. I laughed, but I knew what he meant. It is easy to think of men who navigated the literary world together: Jonson and Shakespeare, Wordsworth and Coleridge, Johnson and Boswell, Shelley and Byron, Marx and Engels, Sartre and Camus, Bellow and Roth, Hughes and Heaney, Amis and Barnes. In Weimar for a day in summer 2014, bitter laughter rose in me when I emerged into Theaterplatz to find a monument to literary bro-dom: Goethe and Schiller in bronze, each with a hand on a shared crown of laurels. With stout folds in Goethe’s breeches and pupils missing from Schiller’s eyes, the unlovely statue had been cast in 1857, twenty-five years after Goethe died, and had stood for more than a century facing the stage where Goethe had directed many of Schiller’s plays. In the early twentieth century, copies of the monument were made for San Francisco, Cleveland, Milwaukee and Syracuse and erected in parks in those cities. I laughed some more when I found that out. Is there such a thing as jealous laughter? If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

If not for the photographs I might have a hard time believing they ever existed. The pensive infant with the swipe of dark bangs and the black button eyes of a Raggedy Andy doll. The placid baby with the yellow ringlets and the high piping voice. The sturdy toddler with the lower lip that curled into an apostrophe above her chin.

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate:

Ana Palacio in Project Syndicate: anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar:

anjay Subramanyam in Sidecar: B

B