Louis Menand in The New Yorker:

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

This does read like a novel. Is it nonfiction? The only source the author cites for this paragraph verifies the statement “weeks of severe cold.” Presumably, the “Christmas storm” has a source, too, perhaps in newspapers of the time (1776). The rest—the light, the exact depth of frozen ground, the packed ice, the ruts, the riders’ mindfulness, the walking horses—seems to have been extrapolated in order to unfold a dramatic scene, evoke a mental picture. There is also the novelistic device of delaying the identification of the characters. It isn’t until the third paragraph that we learn that one of the horsemen is none other than John Adams! It’s all perfectly plausible, but much of it is imagined. Is being “creative” simply a license to embellish? Is there a point beyond which inference becomes fantasy?

More here.

After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”:

After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”: Charles Simic, the late, great Serbian-American poet, was born in 1938 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. In 1941, when Simic was three, Hitler invaded, and a bomb explosion hurled Simic out of bed. Three years later, in 1944, another series of detonations exploded across town—this time, dropped by Allies. Images of a war-torn country inform Simic’s earliest memories. Belgrade had become a chess board, a deadly battleground for both the Nazis and Allies. Simic emigrated as a boy to the United States, and he wrote poetry in English, but the hellish landscape of his youth lay at the heart of his work.

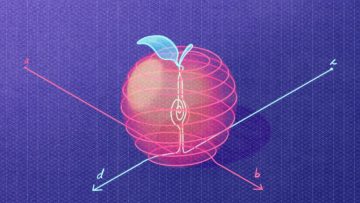

Charles Simic, the late, great Serbian-American poet, was born in 1938 in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. In 1941, when Simic was three, Hitler invaded, and a bomb explosion hurled Simic out of bed. Three years later, in 1944, another series of detonations exploded across town—this time, dropped by Allies. Images of a war-torn country inform Simic’s earliest memories. Belgrade had become a chess board, a deadly battleground for both the Nazis and Allies. Simic emigrated as a boy to the United States, and he wrote poetry in English, but the hellish landscape of his youth lay at the heart of his work. The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector.

The key is that each piece of information, such as the notion of a car, or its make, model or color, or all of it together, is represented as a single entity: a hyperdimensional vector. To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation.

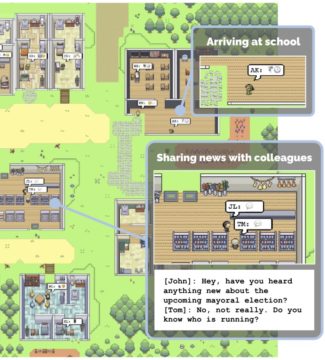

To most people today, the notion of a leisure ethic will sound foreign, paradoxical, and indeed subversive, even though leisure is still commonly associated with the good life. More than any other society in the past, ours certainly has the technology and the wealth to furnish more people with greater freedom over more of their time. Yet because we lack a shared leisure ethic, we have not availed ourselves of that option. Nor does it occur to us even to demand or strive for such a dispensation. The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party.

The researchers found that their agents could “produce believable individual and emergent social behaviors.” For instance, one agent attempted to throw a Valentine’s Day party by sending out invites and setting a time and place for the party. The thought of adding crickets to a summer gazpacho or making your tacos out of honey bee moths is likely to make the majority of us squirm. But faced with a future of growing food scarcity, insects may soon become a kitchen staple; a regular ingredient in our everyday cooking. In Beatle in the box, Italian photographers Michela Benaglia and Emanuela Colombo combine various genres such as still life and food photography in a bid to normalize this fact visually. Rich with proteins, vitamins, carbs, omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, iron and other micronutrients, bugs and beasties have a low environmental-impact as food. They are small, meaning they cause less greenhouse gasses which is an important factor in livestock farming, and they can also be bred easily with few resources. In short, they might be the food of our future. The photographers propose a handy comparison: the growth and spread of sushi through the West in the 1990s—first as a trend, then as a food business.

The thought of adding crickets to a summer gazpacho or making your tacos out of honey bee moths is likely to make the majority of us squirm. But faced with a future of growing food scarcity, insects may soon become a kitchen staple; a regular ingredient in our everyday cooking. In Beatle in the box, Italian photographers Michela Benaglia and Emanuela Colombo combine various genres such as still life and food photography in a bid to normalize this fact visually. Rich with proteins, vitamins, carbs, omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, iron and other micronutrients, bugs and beasties have a low environmental-impact as food. They are small, meaning they cause less greenhouse gasses which is an important factor in livestock farming, and they can also be bred easily with few resources. In short, they might be the food of our future. The photographers propose a handy comparison: the growth and spread of sushi through the West in the 1990s—first as a trend, then as a food business. Among the many unique experiences of reporting on A.I. is this: In a young industry flooded with hype and money, person after person tells me that they are desperate to be regulated, even if it slows them down. In fact, especially if it slows them down. What they tell me is obvious to anyone watching. Competition is forcing them to go too fast and cut too many corners. This technology is too important to be left to a race between Microsoft, Google, Meta and a few other firms. But no one company can slow down to a safe pace without risking irrelevancy. That’s where the government comes in — or so they hope.

Among the many unique experiences of reporting on A.I. is this: In a young industry flooded with hype and money, person after person tells me that they are desperate to be regulated, even if it slows them down. In fact, especially if it slows them down. What they tell me is obvious to anyone watching. Competition is forcing them to go too fast and cut too many corners. This technology is too important to be left to a race between Microsoft, Google, Meta and a few other firms. But no one company can slow down to a safe pace without risking irrelevancy. That’s where the government comes in — or so they hope. “They could never believe in a giant fish that holds a whole world. They’d laugh. They’d scoff. Even if they saw it, they wouldn’t believe it. That is why the human race is dying — too limited an imagination.”

“They could never believe in a giant fish that holds a whole world. They’d laugh. They’d scoff. Even if they saw it, they wouldn’t believe it. That is why the human race is dying — too limited an imagination.” A

A

Lee Harris in The American Prospect:

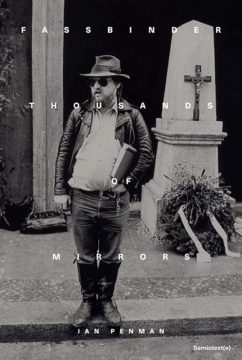

Lee Harris in The American Prospect: Charlie Tyson in Jewish Currents:

Charlie Tyson in Jewish Currents: