Jodi Dean in LA Review of Books:

Jodi Dean in LA Review of Books:

AT A RALLY in 2019, California Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon announced, “When you hear about folks talking about the new economy, the gig economy, the innovation economy, it’s fucking feudalism all over again.” Rendon was there to support legislation classifying most gig workers as employees rather than independent contractors. Assembly Bill 5 was intended to bring gig workers under the protection of existing California labor laws, and the bill passed. But the following year, California voters chose feudalism: they approved Proposition 22, a ballot measure heavily funded by Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Instacart, that would exempt app-based drivers from the labor protections that Assembly Bill 5 tried to secure. In March 2023, a state appellate court upheld Prop 22. By making exceptions for the big transportation and delivery apps, by saying that employment laws do not apply to them, California is entrenching the labor relations—the feudalism—that Rendon warned against.

California has long been at the neofeudal vanguard. Sea Ranch, the northern coastal community founded in the 1960s, ushered in the walled settlements and private enclaves that would come to dominate the US housing landscape. California has more private security businesses than any other state (close to double that of Florida, its closest competitor). It also has more charter schools—that is, schools exempted from some state and district laws. California is at the ideological forefront of movements that seek to protect capitalism from democracy, that model communities on corporations, and that idealize the European Middle Ages. While warnings about the unfreedom and deprivation facing a society of servants come at us from all sides, Silicon Valley tech-lords and venture-capitalist libertarians are dreaming up experiments for seceding from, carving up, and perforating nation-states into a neofeudal patchwork of authority and jurisdiction.

More here.

One of the most useful metaphors for driving scientific and engineering progress has been that of the “machine.” But in light of our increased understanding of biology, evolution, intelligence, and engineering we must re-examine the life-as-machine metaphor with fair, up-to-date definitions. Such a process is allowing us to see that living things are in fact remarkable, agential, morally-important machines, writes Michael Levin.

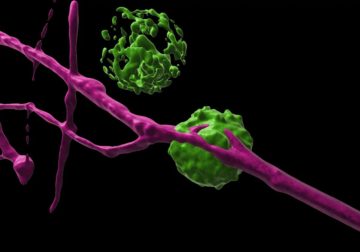

One of the most useful metaphors for driving scientific and engineering progress has been that of the “machine.” But in light of our increased understanding of biology, evolution, intelligence, and engineering we must re-examine the life-as-machine metaphor with fair, up-to-date definitions. Such a process is allowing us to see that living things are in fact remarkable, agential, morally-important machines, writes Michael Levin. Relics of ancient viruses – that have spent millions of years hiding inside human DNA – help the body fight cancer, say scientists. The study by the Francis Crick Institute showed the dormant remnants of these old viruses are woken up when cancerous cells spiral out of control. This unintentionally helps the immune system target and attack the tumour. The team wants to harness the discovery to design vaccines that can boost cancer treatment, or even prevent it. The researchers had noticed a connection between better survival from lung cancer and a part of the immune system, called B-cells, clustering around tumours.

Relics of ancient viruses – that have spent millions of years hiding inside human DNA – help the body fight cancer, say scientists. The study by the Francis Crick Institute showed the dormant remnants of these old viruses are woken up when cancerous cells spiral out of control. This unintentionally helps the immune system target and attack the tumour. The team wants to harness the discovery to design vaccines that can boost cancer treatment, or even prevent it. The researchers had noticed a connection between better survival from lung cancer and a part of the immune system, called B-cells, clustering around tumours. Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie There is no guarantee that someone in the foreseeable future won’t develop dangerous autonomous AI systems with behaviors that deviate from human goals and values. The short and medium term risks –manipulation of public opinion for political purposes, especially through disinformation– are easy to predict, unlike the longer term risks –AI systems that are harmful despite the programmers’ objectives,– and I think it is important to study both.

There is no guarantee that someone in the foreseeable future won’t develop dangerous autonomous AI systems with behaviors that deviate from human goals and values. The short and medium term risks –manipulation of public opinion for political purposes, especially through disinformation– are easy to predict, unlike the longer term risks –AI systems that are harmful despite the programmers’ objectives,– and I think it is important to study both. This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly bravely addresses the hotly contested word freedom. It is hotly contested in part because what the word means has never been clear, a fact that has not seemed to lessen its importance for us. It is a word in which we have invested enormous amounts of energy without producing much in the way of illumination. And yet freedom cannot be dismissed simply on semantic grounds—“just another word,” as Kris Kristofferson sang—because what is at its heart may very well answer the question “What does it mean to be human?”

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly bravely addresses the hotly contested word freedom. It is hotly contested in part because what the word means has never been clear, a fact that has not seemed to lessen its importance for us. It is a word in which we have invested enormous amounts of energy without producing much in the way of illumination. And yet freedom cannot be dismissed simply on semantic grounds—“just another word,” as Kris Kristofferson sang—because what is at its heart may very well answer the question “What does it mean to be human?” S

S

Nowadays the title reads not only as tepid and banal but as distinctly unrepresentative of the ensuing narrative’s principal themes and contours. In fairness, when the onetime Austro-Hungarian actress and subsequently Hollywood scenarist Salka Viertel first began auditioning the phrase “the kindness of strangers” for the title of her memoir in progress, back in the mid-1950s, as her recent biographer Donna Rifkind has pointed out, the words were not nearly as hackneyed as they are today. (The sensational play A Streetcar Named Desire, from which they sprang, was only a few years old, having premiered in 1947; the film had only been released in 1951; and the primary chestnut to have emerged from the latter was Stanley’s bloodcurdling scream of “Stella! Stellllaaaa!” and not so much Blanche’s breathy Southern belle protestations of having always reliii-ed on the kindness of strangers.) Salka’s husband, the internationally acclaimed theater director Berthold Viertel, had been translating their friend Tennessee Williams’s plays for some years already and staging them all over Europe, and perhaps Salka savored the nod in the young playwright’s direction. Such selfless generosity, indeed such kindness on her own part, would have been just like her.

Nowadays the title reads not only as tepid and banal but as distinctly unrepresentative of the ensuing narrative’s principal themes and contours. In fairness, when the onetime Austro-Hungarian actress and subsequently Hollywood scenarist Salka Viertel first began auditioning the phrase “the kindness of strangers” for the title of her memoir in progress, back in the mid-1950s, as her recent biographer Donna Rifkind has pointed out, the words were not nearly as hackneyed as they are today. (The sensational play A Streetcar Named Desire, from which they sprang, was only a few years old, having premiered in 1947; the film had only been released in 1951; and the primary chestnut to have emerged from the latter was Stanley’s bloodcurdling scream of “Stella! Stellllaaaa!” and not so much Blanche’s breathy Southern belle protestations of having always reliii-ed on the kindness of strangers.) Salka’s husband, the internationally acclaimed theater director Berthold Viertel, had been translating their friend Tennessee Williams’s plays for some years already and staging them all over Europe, and perhaps Salka savored the nod in the young playwright’s direction. Such selfless generosity, indeed such kindness on her own part, would have been just like her. Walter was tall and gaunt with a hard-to-place, vaguely English accent. He favored Kools and Chardonnay, and he was never photographed in anything but a dark suit, a tiny smile often curling at the corner of his mouth. His public profile was about to explode. A publisher was finalizing a book about the

Walter was tall and gaunt with a hard-to-place, vaguely English accent. He favored Kools and Chardonnay, and he was never photographed in anything but a dark suit, a tiny smile often curling at the corner of his mouth. His public profile was about to explode. A publisher was finalizing a book about the  Nothing really prepares one for the experience of entering the

Nothing really prepares one for the experience of entering the  Last August, the author

Last August, the author  For the last 60 years or so, science has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth.

For the last 60 years or so, science has been running an experiment on itself. The experimental design wasn’t great; there was no randomization and no control group. Nobody was in charge, exactly, and nobody was really taking consistent measurements. And yet it was the most massive experiment ever run, and it included every scientist on Earth. Many opponents of Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul have called for Israel to finally draft a constitution, but any serious attempt will mean choosing between a democratic state and one that privileges Jewish citizens above all others.

Many opponents of Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul have called for Israel to finally draft a constitution, but any serious attempt will mean choosing between a democratic state and one that privileges Jewish citizens above all others. “She had no sympathy,” Spiegelman tells us, “for people who paraded their inner misfortunes.” Clampitt’s dismissive attitude toward the self-indulgences of confessional verse, which commanded so much attention in the 1960s and 1970s, was a product, he writes, of “her stern midwestern upbringing.” And her models: Hopkins,

“She had no sympathy,” Spiegelman tells us, “for people who paraded their inner misfortunes.” Clampitt’s dismissive attitude toward the self-indulgences of confessional verse, which commanded so much attention in the 1960s and 1970s, was a product, he writes, of “her stern midwestern upbringing.” And her models: Hopkins,