Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

The Republican political consultant Richard Berman is something of a legend, often credited with taking the art of negative campaigning on behalf of undisclosed corporate clients to the next level. When “60 Minutes” did a profile of him, in 2007, he was portrayed as the “Dr. Evil” of the Washington influence game. More than a decade later, when I visited his office in downtown D.C., he still had a tongue-in-cheek “Dr. Evil” nameplate on his desk. (“If they call you Mr. Nice Guy, would that be better?” he asked me. “I don’t think so.”) Berman devised an acronym to capture his firm’s aggressive approach to politics: flags—fear, love, anger, greed, and sympathy. Of those, he believed, anger and fear were undoubtedly the most effective.

The Republican political consultant Richard Berman is something of a legend, often credited with taking the art of negative campaigning on behalf of undisclosed corporate clients to the next level. When “60 Minutes” did a profile of him, in 2007, he was portrayed as the “Dr. Evil” of the Washington influence game. More than a decade later, when I visited his office in downtown D.C., he still had a tongue-in-cheek “Dr. Evil” nameplate on his desk. (“If they call you Mr. Nice Guy, would that be better?” he asked me. “I don’t think so.”) Berman devised an acronym to capture his firm’s aggressive approach to politics: flags—fear, love, anger, greed, and sympathy. Of those, he believed, anger and fear were undoubtedly the most effective.

I’ve often thought of Berman’s formula while watching the descending spiral of American politics in the past few years. It’s not all that complicated, unfortunately: fear and anger, peddled by a skilled demagogue like Donald Trump, have captivated a large segment of the Republican electorate. Other politicians, recognizing Trump’s appeal, also increasingly eschew love, sympathy, and even greed in favor of this simpler and more straightforward approach.

More here.

Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera in the LA Review of Books:

Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera in the LA Review of Books: Lee Harris in Foreign Policy:

Lee Harris in Foreign Policy: I

I While reading “What an Owl Knows,” by the science writer Jennifer Ackerman, I was reminded that my daughter once received a gift of a winter jacket festooned with colorful owls. At the time I thought of the coat as merely cute, but it turns out that the very existence of such merchandise reflects certain cultural assumptions about the birds: namely, that they are salutary and good.

While reading “What an Owl Knows,” by the science writer Jennifer Ackerman, I was reminded that my daughter once received a gift of a winter jacket festooned with colorful owls. At the time I thought of the coat as merely cute, but it turns out that the very existence of such merchandise reflects certain cultural assumptions about the birds: namely, that they are salutary and good. Studying “Hamlet,” the revenge play about a rotten kingdom, I tried for years to fathom Hamlet’s motives, state of mind, family web, obsessions.

Studying “Hamlet,” the revenge play about a rotten kingdom, I tried for years to fathom Hamlet’s motives, state of mind, family web, obsessions. I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through.

I can tell you where it all started because I remember the moment exactly. It was late and I’d just finished the novel I’d been reading. A few more pages would send me off to sleep, so I went in search of a short story. They aren’t hard to come by around here; my office is made up of piles of books, mostly advance-reader copies that have been sent to me in hopes I’ll write a quote for the jacket. They arrive daily in padded mailers—novels, memoirs, essays, histories—things I never requested and in most cases will never get to. On this summer night in 2017, I picked up a collection called Uncommon Type, by Tom Hanks. It had been languishing in a pile by the dresser for a while, and I’d left it there because of an unarticulated belief that actors should stick to acting. Now for no particular reason I changed my mind. Why shouldn’t Tom Hanks write short stories? Why shouldn’t I read one? Off we went to bed, the book and I, and in doing so put the chain of events into motion. The story has started without my realizing it. The first door opened and I walked through. I was left wondering after a moment of peak Simon Schama – where we are led from his ‘idle’ purchase in Paris of a slim old book on Marcel Proust’s father, Adrien, to his own bookshelves by the Hudson River – whether great historians must have something close to a Proustian affinity for a particular period of history, one they understand not simply as a result of study but which they inhabit emotionally, with a quality not far separated from a kind of memory. The reason why the dim fog of mid-medieval western Europe was cleared by Richard Southern is because he understood that world at an elemental level and could translate that understanding to the reader. The same is true when it comes to Steven Runciman writing on Crusade-torn Byzantium, Eamon Duffy on England on the eve of the Reformation and David Brading on early colonial Latin America.

I was left wondering after a moment of peak Simon Schama – where we are led from his ‘idle’ purchase in Paris of a slim old book on Marcel Proust’s father, Adrien, to his own bookshelves by the Hudson River – whether great historians must have something close to a Proustian affinity for a particular period of history, one they understand not simply as a result of study but which they inhabit emotionally, with a quality not far separated from a kind of memory. The reason why the dim fog of mid-medieval western Europe was cleared by Richard Southern is because he understood that world at an elemental level and could translate that understanding to the reader. The same is true when it comes to Steven Runciman writing on Crusade-torn Byzantium, Eamon Duffy on England on the eve of the Reformation and David Brading on early colonial Latin America. I got the call late on a summer afternoon. Yanai Segal, an artist I’ve known for years, asked me whether I’d heard of the Salvator Mundi—the painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that was lost for more than two centuries before resurfacing in New Orleans in 2005. I told him that I’d heard something of the story but that I didn’t remember the details. He had recently undertaken a project related to the painting, he said, and wanted to tell me about it. I was eager to hear more, but first I needed to remind myself of the basic facts. We agreed to speak again soon.

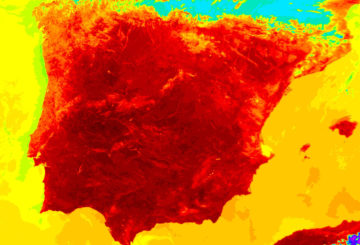

I got the call late on a summer afternoon. Yanai Segal, an artist I’ve known for years, asked me whether I’d heard of the Salvator Mundi—the painting attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that was lost for more than two centuries before resurfacing in New Orleans in 2005. I told him that I’d heard something of the story but that I didn’t remember the details. He had recently undertaken a project related to the painting, he said, and wanted to tell me about it. I was eager to hear more, but first I needed to remind myself of the basic facts. We agreed to speak again soon. The trouble is not ignorance: we know that heat can kill. Humans have recognized the threat for millennia, and over the last two centuries they have scrutinized heat wave mortality to understand who is most at risk and to develop strategies to prevent those deaths. Still people die. Similarly, we have developed strategies that could moderate climate disaster due to global warming, but our fossil fuel

The trouble is not ignorance: we know that heat can kill. Humans have recognized the threat for millennia, and over the last two centuries they have scrutinized heat wave mortality to understand who is most at risk and to develop strategies to prevent those deaths. Still people die. Similarly, we have developed strategies that could moderate climate disaster due to global warming, but our fossil fuel  Rapid progress in the development of artificial intelligence has been too rapid for many, including pioneers of the technology, who are now issuing dire warnings about the future of our economies, democracies, and humanity itself. But AI is hardly the first technological advance that has been portrayed as an existential threat.

Rapid progress in the development of artificial intelligence has been too rapid for many, including pioneers of the technology, who are now issuing dire warnings about the future of our economies, democracies, and humanity itself. But AI is hardly the first technological advance that has been portrayed as an existential threat. So are we really essentially the same animals as the early Homo sapiens hunting and gathering on the savannahs? Dartnell thinks so. “The fundamental aspects of what it means to be human – the hardware of our bodies and the software of our minds – haven’t changed.” This is, indeed, the assumption behind evolutionary psychology, which seeks to explain modern human behaviour in terms of what is hypothesised to have been adaptive for our cave-dwelling ancestors. But his mainframe-age metaphor of hardware and software is old hat and inaccurate. We now know that the human brain exhibits substantial neuroplasticity: in other words, the “software” can change the “hardware” it’s running on, as is not the case for any actual computer.

So are we really essentially the same animals as the early Homo sapiens hunting and gathering on the savannahs? Dartnell thinks so. “The fundamental aspects of what it means to be human – the hardware of our bodies and the software of our minds – haven’t changed.” This is, indeed, the assumption behind evolutionary psychology, which seeks to explain modern human behaviour in terms of what is hypothesised to have been adaptive for our cave-dwelling ancestors. But his mainframe-age metaphor of hardware and software is old hat and inaccurate. We now know that the human brain exhibits substantial neuroplasticity: in other words, the “software” can change the “hardware” it’s running on, as is not the case for any actual computer. No, it’s not. Participants in our studies tell us that people are less kind, less nice, less honest, less good, that this has been happening their whole lives, that it’s been happening recently, and that it’s been happening everywhere. Which should make it pretty easy to find some evidence of this somewhere, and we find no evidence of it anywhere. In fact, we find pretty good evidence that it

No, it’s not. Participants in our studies tell us that people are less kind, less nice, less honest, less good, that this has been happening their whole lives, that it’s been happening recently, and that it’s been happening everywhere. Which should make it pretty easy to find some evidence of this somewhere, and we find no evidence of it anywhere. In fact, we find pretty good evidence that it  Dear Reader,

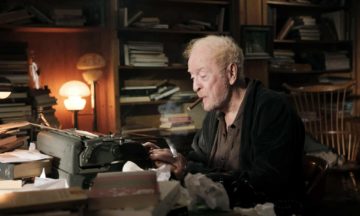

Dear Reader, The actor, 90, has long harboured the desire to write a thriller, and was inspired to do so by a news item, says his UK publisher, Hodder’s Rowena Webb, about “the discovery of uranium by workers on a dump in London’s East End”. The novel’s lead character is DCI Harry Taylor, who, according to the synopsis, is “called in when just such a package is found, mysteriously abandoned in Stepney and stolen before the police can reclaim it. As security agencies around the world go to red alert, it is former SAS man Harry and his small team from the Met who must race against time to find who has the nuclear material and what they plan to do with it.”

The actor, 90, has long harboured the desire to write a thriller, and was inspired to do so by a news item, says his UK publisher, Hodder’s Rowena Webb, about “the discovery of uranium by workers on a dump in London’s East End”. The novel’s lead character is DCI Harry Taylor, who, according to the synopsis, is “called in when just such a package is found, mysteriously abandoned in Stepney and stolen before the police can reclaim it. As security agencies around the world go to red alert, it is former SAS man Harry and his small team from the Met who must race against time to find who has the nuclear material and what they plan to do with it.”