Sally Rooney in The Paris Review:

In 1923, the year after James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was first published in its complete form, T. S. Eliot wrote: “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” Although Ulysses was not yet widely available at the time—its initial print runs were minuscule and it would be banned repeatedly by censorship boards—Eliot was writing in defense of a novel already broadly disparaged as immoral, obscene, formless, and chaotic. His friend Virginia Woolf had described it in her diary as “an illiterate, underbred book … the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are.” In comparison, Eliot’s praise is triumphal. “A book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” And yet this proposed relationship between Ulysses and its readers may not seem altogether inviting either. Do we really want to read a novel in order to experience the sensation of inescapable debt? In the century since its publication, Ulysses has of course become a monument not only of modernist literature but of the novel itself. But it’s also a notoriously “difficult” book. Among all English-language novels, there may be no greater gulf between how much a work is celebrated and discussed, and how seldom it is actually read.

In 1923, the year after James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was first published in its complete form, T. S. Eliot wrote: “I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” Although Ulysses was not yet widely available at the time—its initial print runs were minuscule and it would be banned repeatedly by censorship boards—Eliot was writing in defense of a novel already broadly disparaged as immoral, obscene, formless, and chaotic. His friend Virginia Woolf had described it in her diary as “an illiterate, underbred book … the book of a self-taught working man, & we all know how distressing they are.” In comparison, Eliot’s praise is triumphal. “A book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.” And yet this proposed relationship between Ulysses and its readers may not seem altogether inviting either. Do we really want to read a novel in order to experience the sensation of inescapable debt? In the century since its publication, Ulysses has of course become a monument not only of modernist literature but of the novel itself. But it’s also a notoriously “difficult” book. Among all English-language novels, there may be no greater gulf between how much a work is celebrated and discussed, and how seldom it is actually read.

More here.

We now have a good explanation for how our brain keeps track of a conversation while we are in a loud, crowded room, a discovery that could improve hearing aids.

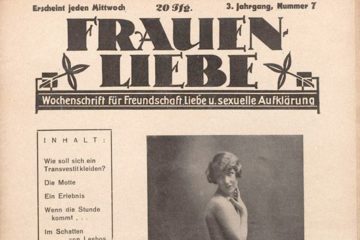

We now have a good explanation for how our brain keeps track of a conversation while we are in a loud, crowded room, a discovery that could improve hearing aids. Berlin in the 1920s was ablaze with sexual and gender freedom. Magazines at newsstands boasted covers featuring people who were transgender and clad scantily. Their headlines touted stories on “Homosexual Women and the Upcoming Legislative Elections,” and offered, on occasion, homoerotic fiction inside its pages.

Berlin in the 1920s was ablaze with sexual and gender freedom. Magazines at newsstands boasted covers featuring people who were transgender and clad scantily. Their headlines touted stories on “Homosexual Women and the Upcoming Legislative Elections,” and offered, on occasion, homoerotic fiction inside its pages. To tackle the world’s mounting plastics problem, humans may have to use every tool in the arsenal—even microscopic bacteria and fungi. High in the Swiss Alps and the Arctic, scientists have discovered microbes that can digest plastics—importantly, without the need to apply excess heat. Their findings, published this month in the journal

To tackle the world’s mounting plastics problem, humans may have to use every tool in the arsenal—even microscopic bacteria and fungi. High in the Swiss Alps and the Arctic, scientists have discovered microbes that can digest plastics—importantly, without the need to apply excess heat. Their findings, published this month in the journal  In 2003, Ken Jennings was a twenty-nine-year-old software engineer, living in a suburb of Salt Lake City with his wife and young son, when his old college roommate suggested that they try out for “Jeopardy!” A year later, Jennings, a trivia enthusiast who’d grown up watching the show, made it on the air, had a seventy-four-game winning streak, and won more than $2.5 million, becoming the winningest “Jeopardy!” contestant of all time. (He still is: a year and a half ago, Amy Schneider, the second-winningest, won forty consecutive games.) After Alex Trebek, the show’s beloved host, died in 2020, the show endured an uneasy era of temporary hosts and executive blunders. But now Jennings helms the show, in rotation with Mayim Bialik—and “Jeopardy!,” that reliable source of answers-in-the-form-of-a-question comfort, once again feels like it’s in good hands. Jennings is a natural, ably enhancing the game’s inherent charms with warmth and wit, fostering an atmosphere of collegial curiosity. He even manages to make the show’s personal-anecdote segment the least awkward it’s ever been.

In 2003, Ken Jennings was a twenty-nine-year-old software engineer, living in a suburb of Salt Lake City with his wife and young son, when his old college roommate suggested that they try out for “Jeopardy!” A year later, Jennings, a trivia enthusiast who’d grown up watching the show, made it on the air, had a seventy-four-game winning streak, and won more than $2.5 million, becoming the winningest “Jeopardy!” contestant of all time. (He still is: a year and a half ago, Amy Schneider, the second-winningest, won forty consecutive games.) After Alex Trebek, the show’s beloved host, died in 2020, the show endured an uneasy era of temporary hosts and executive blunders. But now Jennings helms the show, in rotation with Mayim Bialik—and “Jeopardy!,” that reliable source of answers-in-the-form-of-a-question comfort, once again feels like it’s in good hands. Jennings is a natural, ably enhancing the game’s inherent charms with warmth and wit, fostering an atmosphere of collegial curiosity. He even manages to make the show’s personal-anecdote segment the least awkward it’s ever been. Maybe one sign of being an important writer is how much attention you receive when you die. Tributes to and remembrances of Martin Amis, who died last week at 73, have been appearing all over the place, like fresh bouquets of sympathy sent to a funeral. I almost found myself lazily inserting the phrase “after a long battle with cancer” to specify the conditions of his demise, but since Amis was famously at war with cliches, this would not do. Amis refused to hide his taste, his opinions, and above all, his style under a bushel, and this is why people loved him on both sides of the Atlantic.

Maybe one sign of being an important writer is how much attention you receive when you die. Tributes to and remembrances of Martin Amis, who died last week at 73, have been appearing all over the place, like fresh bouquets of sympathy sent to a funeral. I almost found myself lazily inserting the phrase “after a long battle with cancer” to specify the conditions of his demise, but since Amis was famously at war with cliches, this would not do. Amis refused to hide his taste, his opinions, and above all, his style under a bushel, and this is why people loved him on both sides of the Atlantic. Will we ever decipher the language of molecular biology? Here, I argue that we are just a few years away from having accurate in silico models of the primary biomolecular information highway — from DNA to gene expression to proteins — that rival experimental accuracy and can be used in medicine and pharmaceutical discovery.

Will we ever decipher the language of molecular biology? Here, I argue that we are just a few years away from having accurate in silico models of the primary biomolecular information highway — from DNA to gene expression to proteins — that rival experimental accuracy and can be used in medicine and pharmaceutical discovery. At the end of the Korean war in 1953, captured American soldiers were allowed to return home. To widespread amazement, some declined the offer and followed their captors to China. A popular explanation quickly emerged. The Chinese army had undertaken an unusual project with its prisoners of war: through intense and sustained attempts at persuasion—using tactics such as sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, and exposure to propaganda—it had sought to convince them of the superiority of communism over capitalism. Amid the general paranoia of 1950s McCarthyism, the fact that such techniques had apparently achieved some success produced considerable alarm. The soldiers had been “

At the end of the Korean war in 1953, captured American soldiers were allowed to return home. To widespread amazement, some declined the offer and followed their captors to China. A popular explanation quickly emerged. The Chinese army had undertaken an unusual project with its prisoners of war: through intense and sustained attempts at persuasion—using tactics such as sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, and exposure to propaganda—it had sought to convince them of the superiority of communism over capitalism. Amid the general paranoia of 1950s McCarthyism, the fact that such techniques had apparently achieved some success produced considerable alarm. The soldiers had been “ When an ice cube melts and attains equilibrium with the liquid, physicists usually say the evolution of the system has ended. But it hasn’t — there is life after heat death. Weird and wonderful things continue to happen at the quantum level. “If you really look into a quantum system, the particle distribution might have equilibrated, and the energy distribution might have equilibrated, but there’s still so much more going on beyond that,” said

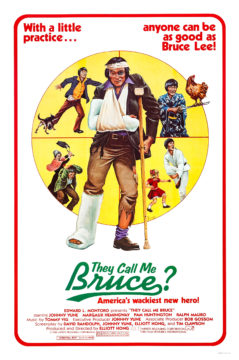

When an ice cube melts and attains equilibrium with the liquid, physicists usually say the evolution of the system has ended. But it hasn’t — there is life after heat death. Weird and wonderful things continue to happen at the quantum level. “If you really look into a quantum system, the particle distribution might have equilibrated, and the energy distribution might have equilibrated, but there’s still so much more going on beyond that,” said  In the conventional canon of Asian American cinema, you’re unlikely to find They Call Me Bruce mentioned. This is in spite of the fact that it arrived right after Wayne Wang’s lauded debut, Chan Is Missing (1982), as arguably the second Asian American feature to ever gain theatrical distribution (and probably the first to turn a substantial profit). This makes its absence from the canon all the more curious, and both They Call Me Bruce and its primary creators are overdue a reconsideration.

In the conventional canon of Asian American cinema, you’re unlikely to find They Call Me Bruce mentioned. This is in spite of the fact that it arrived right after Wayne Wang’s lauded debut, Chan Is Missing (1982), as arguably the second Asian American feature to ever gain theatrical distribution (and probably the first to turn a substantial profit). This makes its absence from the canon all the more curious, and both They Call Me Bruce and its primary creators are overdue a reconsideration. It wasn’t the singing; it was the song. When Deanie Parker hit her last high note in the studio, and the band’s final chord faded behind her, the producer gave her a long, appraising look. She’d be great onstage, with those sugarplum features and defiant eyes, and that voice could knock down walls. “You sound good,” he said. “But if we’re going to cut a record, you’ve got to have your own song. A song that you created. We can’t introduce a new artist covering somebody else’s song.” Did she have any original material? Parker stared at him blankly for a moment, then shook her head.

It wasn’t the singing; it was the song. When Deanie Parker hit her last high note in the studio, and the band’s final chord faded behind her, the producer gave her a long, appraising look. She’d be great onstage, with those sugarplum features and defiant eyes, and that voice could knock down walls. “You sound good,” he said. “But if we’re going to cut a record, you’ve got to have your own song. A song that you created. We can’t introduce a new artist covering somebody else’s song.” Did she have any original material? Parker stared at him blankly for a moment, then shook her head. Birders are a funny bunch, mostly—at this festival, anyway—white, older-aged, and of a delightfully inefficient temperament. In general, they talk and move at a relaxed pace, and are eager to dedicate long moments of their lives to matters that many people simply whisk past. On a geology tour my mom and I took on our third day in Hays, the group revolted and made the guide turn the van around just to take pictures of a flock of turkeys. Later, about a half hour was spent on a quiet debate over whether a falcon in a far-off tree was a kestrel or a much more uncommon merlin. I listened to a man trying in vain for several minutes to describe the position of the falcon to the woman next to him: “It’s in the backmost tree, up there on the white branch. There are a lot of light branches. But no! There’s only one white branch.” Over the course of the trip, time seemed to slow down to match the geologic scale suggested by the ancient mating rituals of the prairie chickens and the landscape that surrounds them: sprawling fields of grass punctuated by chalk formations left over from Kansas’s past beneath the Cretaceous-era Western Interior Seaway.

Birders are a funny bunch, mostly—at this festival, anyway—white, older-aged, and of a delightfully inefficient temperament. In general, they talk and move at a relaxed pace, and are eager to dedicate long moments of their lives to matters that many people simply whisk past. On a geology tour my mom and I took on our third day in Hays, the group revolted and made the guide turn the van around just to take pictures of a flock of turkeys. Later, about a half hour was spent on a quiet debate over whether a falcon in a far-off tree was a kestrel or a much more uncommon merlin. I listened to a man trying in vain for several minutes to describe the position of the falcon to the woman next to him: “It’s in the backmost tree, up there on the white branch. There are a lot of light branches. But no! There’s only one white branch.” Over the course of the trip, time seemed to slow down to match the geologic scale suggested by the ancient mating rituals of the prairie chickens and the landscape that surrounds them: sprawling fields of grass punctuated by chalk formations left over from Kansas’s past beneath the Cretaceous-era Western Interior Seaway.