Warren Zanes at Literary Hub:

Shortly after the birth of his sister Virginia in 1951, Springsteen’s family moved in with his paternal grandparents. They would stay there through 1956, but the years spent in that house would remain with Springsteen, a thing to untangle. It was a period of his childhood that, in his telling, would come to the fore in Nebraska.

Shortly after the birth of his sister Virginia in 1951, Springsteen’s family moved in with his paternal grandparents. They would stay there through 1956, but the years spent in that house would remain with Springsteen, a thing to untangle. It was a period of his childhood that, in his telling, would come to the fore in Nebraska.

“I know the house was very dilapidated,” Springsteen told me. “That was something that embarrassed me as a child. It was visibly ramshackle, my grandparents’ house. On the street you could see that it was deteriorating. I just remember being embarrassed about it as a child. That would have been my only sense that something wasn’t right with who we were and what we were doing. I can’t quite describe it. It was intense. The house was eventually condemned. Really, it fell apart around us. I lived there when there was only one functional room, the living room. Everything else was pretty much finished.”

In the living room was the portrait of his aunt Virginia, his father’s sister, an image Springsteen has described on a few occasions. Virginia, at age six and out riding her bicycle, was hit and killed by a truck as it pulled out of a gas station on Freehold’s McLean Street. In some misguided tribute to Virginia’s early and sudden death, Springsteen’s grandparents withheld discipline from their first grandchild, Bruce. It was a twisting of logic that likely seemed beneficent, if only to minds stuck in grief. His was a terrible freedom. When Bruce pushed, there was nothing there to push against.

More here.

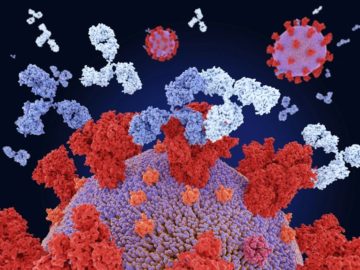

At the height of the pandemic, researchers raced to develop some of the first effective treatments against COVID-19: antibody molecules isolated from the blood of people who had recovered from the disease.

At the height of the pandemic, researchers raced to develop some of the first effective treatments against COVID-19: antibody molecules isolated from the blood of people who had recovered from the disease. One of the staples of my teaching of comparative politics over the years was to point out the differences between European and American conservatives. The former were generally comfortable with the exercise of state power, and indeed sought to use power to enforce religious or cultural values (the old unity of “throne and altar.”) American conservatives, on the other hand, were different in their emphasis on individual liberty, a small state, property rights, and a vigorous private sector. In Seymour Martin Lipset’s

One of the staples of my teaching of comparative politics over the years was to point out the differences between European and American conservatives. The former were generally comfortable with the exercise of state power, and indeed sought to use power to enforce religious or cultural values (the old unity of “throne and altar.”) American conservatives, on the other hand, were different in their emphasis on individual liberty, a small state, property rights, and a vigorous private sector. In Seymour Martin Lipset’s  Living trapped by viruses, surrounded by culturenature, and exposed to all kinds of media—writers, self-help books, chefs, singers, filmmakers, even comedians—I don’t want to be comforted, yet they pounce on me, to comfort me, to empathize. Startled, I get frightened. And, conversely, I become even more frightened when I’m asked who my poetry comforts. Therefore, when someone even utters the word comfort, I want to run and hide. I don’t think I’ve ever comforted anyone with my writing. Moreover, I think literature betrays the readers’ desire to be consoled. Perhaps literature crosses into a zone where consolation can’t intervene, evaporating any possibility of comfort. Just as there is no geometric or genetic consolation, literary work merely constructs an afterimage or alternative symmetrical pattern of the event that occurs. The ventriloquist lives inside literature. Ventriloquy is a deception. The writer first deceives herself. And she deceives the reader. Both are aware of the deception. The persona crosses into a zone of literature, the symmetrical world of existence. Thus literature is a lie. Fiction set as reality is a lie; poetry set as language is a lie. The ventriloquy of literature moves, riding the spiral of lies. And so there can be no consolation at the end of the lies. There is only failure, grief, and self-erasure.

Living trapped by viruses, surrounded by culturenature, and exposed to all kinds of media—writers, self-help books, chefs, singers, filmmakers, even comedians—I don’t want to be comforted, yet they pounce on me, to comfort me, to empathize. Startled, I get frightened. And, conversely, I become even more frightened when I’m asked who my poetry comforts. Therefore, when someone even utters the word comfort, I want to run and hide. I don’t think I’ve ever comforted anyone with my writing. Moreover, I think literature betrays the readers’ desire to be consoled. Perhaps literature crosses into a zone where consolation can’t intervene, evaporating any possibility of comfort. Just as there is no geometric or genetic consolation, literary work merely constructs an afterimage or alternative symmetrical pattern of the event that occurs. The ventriloquist lives inside literature. Ventriloquy is a deception. The writer first deceives herself. And she deceives the reader. Both are aware of the deception. The persona crosses into a zone of literature, the symmetrical world of existence. Thus literature is a lie. Fiction set as reality is a lie; poetry set as language is a lie. The ventriloquy of literature moves, riding the spiral of lies. And so there can be no consolation at the end of the lies. There is only failure, grief, and self-erasure. Boredom: “If I ever bore you, it’ll be with a knife,” Louise Brooks once said, a line that sums up almost about every Fassbinder movie. RWF constantly employed Brechtian distancing devices to put the strange in estrangement, piercing our defenses of “relating to” and “identifying with” characters, situations. It is the feeling that the world’s a film stage and everyone on it is standing on a trapdoor. Fassbinder’s hand is on the lever and Death is in the wings, waiting for a cue.

Boredom: “If I ever bore you, it’ll be with a knife,” Louise Brooks once said, a line that sums up almost about every Fassbinder movie. RWF constantly employed Brechtian distancing devices to put the strange in estrangement, piercing our defenses of “relating to” and “identifying with” characters, situations. It is the feeling that the world’s a film stage and everyone on it is standing on a trapdoor. Fassbinder’s hand is on the lever and Death is in the wings, waiting for a cue.  IN A CAVERNOUS

IN A CAVERNOUS A

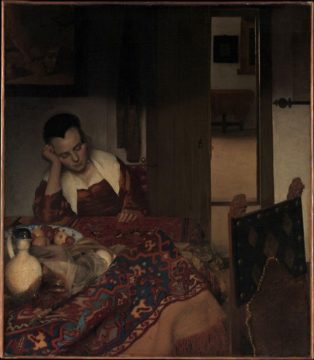

A Sometime probably in 1656 or 1657, Johannes Vermeer painted a painting that we now know as A Maid Asleep. I reference this painting because it hangs at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. I’ve looked at it many times. I have a relationship with this painting. I’ve loved it for years and for that same amount of time I’ve been trying to figure out why.

Sometime probably in 1656 or 1657, Johannes Vermeer painted a painting that we now know as A Maid Asleep. I reference this painting because it hangs at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. I’ve looked at it many times. I have a relationship with this painting. I’ve loved it for years and for that same amount of time I’ve been trying to figure out why. How will voters know whether a video of a political candidate saying something offensive was real or generated by AI? Will people be willing to pay artists for their work when AI can create something visually stunning? Why follow certain authors when stories in their writing style will be freely circulating on the internet?

How will voters know whether a video of a political candidate saying something offensive was real or generated by AI? Will people be willing to pay artists for their work when AI can create something visually stunning? Why follow certain authors when stories in their writing style will be freely circulating on the internet? In a recent Wall Street Journal

In a recent Wall Street Journal  For the past two weeks, in a courtroom in lower Manhattan, the journalist E. Jean Carroll has made a straightforward case: a quarter century ago, she says, Donald Trump raped her. The account she gave in the courtroom was the same as it has been since she first revealed this story, in an excerpt of

For the past two weeks, in a courtroom in lower Manhattan, the journalist E. Jean Carroll has made a straightforward case: a quarter century ago, she says, Donald Trump raped her. The account she gave in the courtroom was the same as it has been since she first revealed this story, in an excerpt of

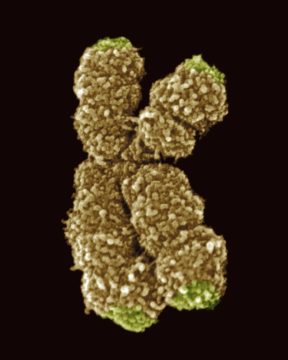

The story, as often happens in science, sounded so appealing. Cells have a molecular clock that determines how long they live. If you can just stop the clock, cells can live indefinitely. And the same should go for people, who are, after all, made from cells. Stop the cell clocks and you can remain youthful.

The story, as often happens in science, sounded so appealing. Cells have a molecular clock that determines how long they live. If you can just stop the clock, cells can live indefinitely. And the same should go for people, who are, after all, made from cells. Stop the cell clocks and you can remain youthful. From December 31, 1957 until December 31, 1967, the artist and writer Henry Darger (1892–1973) kept a series of six ring-binder notebooks with almost daily entries on the weather in his native Chicago. On the outside cover of the first book, Darger describes the project, with encyclopedic enthusiasm, as a “book of weather reports on temperatures, fair cloudy to clear skies, snow, rain, or summer storms, and winter snows and big blizzards—also the low temperatures of severe cold waves and hot spells of summer.”

From December 31, 1957 until December 31, 1967, the artist and writer Henry Darger (1892–1973) kept a series of six ring-binder notebooks with almost daily entries on the weather in his native Chicago. On the outside cover of the first book, Darger describes the project, with encyclopedic enthusiasm, as a “book of weather reports on temperatures, fair cloudy to clear skies, snow, rain, or summer storms, and winter snows and big blizzards—also the low temperatures of severe cold waves and hot spells of summer.”