Ann Bauer in Tablet:

In 2009, I took a job as a copywriter with an ad agency in Minneapolis. After 10 years of academia and publishing in obscure literary magazines, I began writing copy for health care and medical device accounts. The work was boring but the salary was grand, and so I threw myself into learning about stents and dilatation balloons.

In 2009, I took a job as a copywriter with an ad agency in Minneapolis. After 10 years of academia and publishing in obscure literary magazines, I began writing copy for health care and medical device accounts. The work was boring but the salary was grand, and so I threw myself into learning about stents and dilatation balloons.

About a year into the job a large meeting was called. Suddenly my colleagues—those of the running shoe and vodka accounts—wanted in. Our flagship health care client was looking for a multimedia retail campaign for their pacemaker. A pacemaker is a simple device that can be lifesaving, essentially a low-voltage clock used to speed up and regulate a slow or sloppy heart rate. It was developed in the late 1950s and patented in 1962. Since then, the technology has not changed much. The device got smaller and the surgery to insert it more streamlined, but as a mechanical object, the design was pretty perfect.

More here.

Vogel is part of a loose online subculture known as the postrationalists — also known by the jokey endonym “this part of Twitter,” or TPOT. They are a group of writers, thinkers, readers, and Internet trolls alike who were once rationalists, or members of adjacent communities like the effective altruism movement, but grew disillusioned. To them, rationality culture’s technocratic focus on ameliorating the human condition through hyper-utilitarian goals — increasing the number of malaria nets in the developing world, say, or minimizing the existential risk posed by the development of unfriendly artificial intelligence — had come at the expense of taking seriously the less quantifiable elements of a well-lived human life.

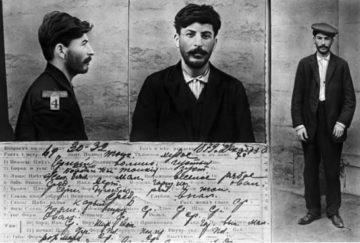

Vogel is part of a loose online subculture known as the postrationalists — also known by the jokey endonym “this part of Twitter,” or TPOT. They are a group of writers, thinkers, readers, and Internet trolls alike who were once rationalists, or members of adjacent communities like the effective altruism movement, but grew disillusioned. To them, rationality culture’s technocratic focus on ameliorating the human condition through hyper-utilitarian goals — increasing the number of malaria nets in the developing world, say, or minimizing the existential risk posed by the development of unfriendly artificial intelligence — had come at the expense of taking seriously the less quantifiable elements of a well-lived human life. Allow me to make the case for understanding the life of Joseph Stalin. It is difficult to think of many people who lived lives more interesting than that of the Soviet dictator. The son of a cobbler and seamstress living from the outskirts of the Russian empire, he would grow up to be at the center of three once-in-a-lifetime type geopolitical events: the Russian Revolution, World War II, and the beginning of the Cold War. Stalin was also the preeminent force behind the drive to build the first communist great power in world history. This included the 1936–1938 purge of the country’s leadership that was perhaps unlike anything documented history had seen before or since. Twenty years after the Russian Revolution, Stalin would wipe out the vast majority of its more prominent figures still alive, in addition to much of the country’s military and intelligence leadership.

Allow me to make the case for understanding the life of Joseph Stalin. It is difficult to think of many people who lived lives more interesting than that of the Soviet dictator. The son of a cobbler and seamstress living from the outskirts of the Russian empire, he would grow up to be at the center of three once-in-a-lifetime type geopolitical events: the Russian Revolution, World War II, and the beginning of the Cold War. Stalin was also the preeminent force behind the drive to build the first communist great power in world history. This included the 1936–1938 purge of the country’s leadership that was perhaps unlike anything documented history had seen before or since. Twenty years after the Russian Revolution, Stalin would wipe out the vast majority of its more prominent figures still alive, in addition to much of the country’s military and intelligence leadership. Could AI soon write your favourite Hollywood film or streaming show? That concern is one of the issues driving a US film and television writers’ strike that has halted many productions nationwide.

Could AI soon write your favourite Hollywood film or streaming show? That concern is one of the issues driving a US film and television writers’ strike that has halted many productions nationwide. Since 1959—when she first appeared, at age eighteen, at the Newport Folk Festival,

Since 1959—when she first appeared, at age eighteen, at the Newport Folk Festival,  Restless and, at some level, always dissatisfied, in the early 1960s, Guston began to step back from his acclaimed abstractions. The floating tangles of dense brushstrokes began to coalesce into dark, confrontational, ample ovals that hovered against murky webs like surrogate self-portraits, an association reinforced by titles like Mirror, Painter, and Head. A period devoted to essentially minimal drawing followed, as if Guston were stripping everything down to essentials, testing what a single assertive mark on paper could mean. Next, he concentrated on small “portraits” of shoes, books, light bulbs, hooded figures, window shades, and the like, with every image filling the available space and pressing toward us, a series that has been described as a visual lexicon, prepared for future works. Guston later said that he was provoked to make images by the events of 1968, including the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy, student uprisings, and police brutality during the Democratic Convention. He felt that worrying about color relationships and formal issues was inadequate to the situation.

Restless and, at some level, always dissatisfied, in the early 1960s, Guston began to step back from his acclaimed abstractions. The floating tangles of dense brushstrokes began to coalesce into dark, confrontational, ample ovals that hovered against murky webs like surrogate self-portraits, an association reinforced by titles like Mirror, Painter, and Head. A period devoted to essentially minimal drawing followed, as if Guston were stripping everything down to essentials, testing what a single assertive mark on paper could mean. Next, he concentrated on small “portraits” of shoes, books, light bulbs, hooded figures, window shades, and the like, with every image filling the available space and pressing toward us, a series that has been described as a visual lexicon, prepared for future works. Guston later said that he was provoked to make images by the events of 1968, including the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy, student uprisings, and police brutality during the Democratic Convention. He felt that worrying about color relationships and formal issues was inadequate to the situation. “Originals,” of course, rarely are.

“Originals,” of course, rarely are. When computer scientists at Microsoft started to experiment with a new artificial intelligence system last year, they asked it to solve a puzzle that should have required an intuitive understanding of the physical world. “Here we have a book, nine eggs, a laptop, a bottle and a nail,” they asked. “Please tell me how to stack them onto each other in a stable manner.” The researchers were startled by the ingenuity of the A.I. system’s answer. Put the eggs on the book, it said. Arrange the eggs in three rows with space between them. Make sure you don’t crack them. “Place the laptop on top of the eggs, with the screen facing down and the keyboard facing up,” it wrote. “The laptop will fit snugly within the boundaries of the book and the eggs, and its flat and rigid surface will provide a stable platform for the next layer.”

When computer scientists at Microsoft started to experiment with a new artificial intelligence system last year, they asked it to solve a puzzle that should have required an intuitive understanding of the physical world. “Here we have a book, nine eggs, a laptop, a bottle and a nail,” they asked. “Please tell me how to stack them onto each other in a stable manner.” The researchers were startled by the ingenuity of the A.I. system’s answer. Put the eggs on the book, it said. Arrange the eggs in three rows with space between them. Make sure you don’t crack them. “Place the laptop on top of the eggs, with the screen facing down and the keyboard facing up,” it wrote. “The laptop will fit snugly within the boundaries of the book and the eggs, and its flat and rigid surface will provide a stable platform for the next layer.” The first time I read Professor Laleh Khalili’s work, I was awed by her political acuity and ingenuity in laying bare contemporary colonial hierarchies. As I digested her work, I absorbed the magnitude precisely because her research methods were fresh in laying out how the Global South has become a laboratory for trade. Not only was Khalili an academic interviewing the formerly incarcerated, but she was also a reflective emissary on cargo ships, dissecting the logistics of trade. Khalili is not just a scholar; she forges community by showing reverence for feminist scholars and writers at all stages of life.

The first time I read Professor Laleh Khalili’s work, I was awed by her political acuity and ingenuity in laying bare contemporary colonial hierarchies. As I digested her work, I absorbed the magnitude precisely because her research methods were fresh in laying out how the Global South has become a laboratory for trade. Not only was Khalili an academic interviewing the formerly incarcerated, but she was also a reflective emissary on cargo ships, dissecting the logistics of trade. Khalili is not just a scholar; she forges community by showing reverence for feminist scholars and writers at all stages of life. It’s easy now to forget how shocking the moment was: just after 4pm on May 11th, 1997, Garry Kasparov resigned in the final game of his highly anticipated chess match against Deep Blue, an IBM supercomputer. A machine had beaten the human world chess champion in a competitive match for the first time. Commentators used to thinking of elite-level chess as a sort of irreducibly human area of excellence—the pinnacle of our species’ intellect—were forced into a moment of humility, reconsidering the topography at the outer limits of human and machine intelligence.

It’s easy now to forget how shocking the moment was: just after 4pm on May 11th, 1997, Garry Kasparov resigned in the final game of his highly anticipated chess match against Deep Blue, an IBM supercomputer. A machine had beaten the human world chess champion in a competitive match for the first time. Commentators used to thinking of elite-level chess as a sort of irreducibly human area of excellence—the pinnacle of our species’ intellect—were forced into a moment of humility, reconsidering the topography at the outer limits of human and machine intelligence. Every day, upon leaving her Catholic high school, Agustina Bazterrica and her friends were followed by the same predatory man who would aim “the most terrible words” in their direction. A different man once masturbated in front of her on a packed train. “No one did anything,” she recalls. Coupled with the epidemic of violence against women in her native Argentina – where

Every day, upon leaving her Catholic high school, Agustina Bazterrica and her friends were followed by the same predatory man who would aim “the most terrible words” in their direction. A different man once masturbated in front of her on a packed train. “No one did anything,” she recalls. Coupled with the epidemic of violence against women in her native Argentina – where  R

R Aristotle called the hand the “tool of tools”; Kant, “the visible part of the brain.” The earliest works of art were handprints on the walls of caves. Throughout history hand gestures have symbolized the range of human experience: power, tenderness, creativity, conflict, even (bravo, Michelangelo) the touch of the divine. Without hands, civilization would be inconceivable. And so the discovery in 2011 of the bones of a dozen right hands, at a site where the ancient Egyptian city of Avaris (today known as Tell el-Dab’a) once stood, was particularly unsettling. The remains were unearthed, most with palms down, from three shallow pits near the throne room of a royal palace. The hands, along with numerous disarticulated fingers, were most likely buried during Egypt’s 15th dynasty, from 1640 B.C. to 1530 B.C. At the time, Egypt’s eastern Nile Delta was controlled by a dynasty called the Hyksos, which means “rulers of foreign countries.”

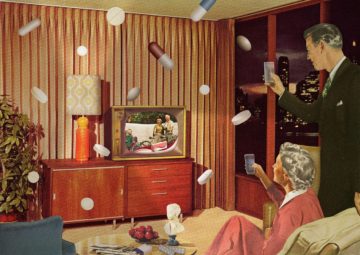

Aristotle called the hand the “tool of tools”; Kant, “the visible part of the brain.” The earliest works of art were handprints on the walls of caves. Throughout history hand gestures have symbolized the range of human experience: power, tenderness, creativity, conflict, even (bravo, Michelangelo) the touch of the divine. Without hands, civilization would be inconceivable. And so the discovery in 2011 of the bones of a dozen right hands, at a site where the ancient Egyptian city of Avaris (today known as Tell el-Dab’a) once stood, was particularly unsettling. The remains were unearthed, most with palms down, from three shallow pits near the throne room of a royal palace. The hands, along with numerous disarticulated fingers, were most likely buried during Egypt’s 15th dynasty, from 1640 B.C. to 1530 B.C. At the time, Egypt’s eastern Nile Delta was controlled by a dynasty called the Hyksos, which means “rulers of foreign countries.” THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT VIDEO ART that calls for grand theories and epic summations, wild pronouncements and heroic declarations. It’s exciting to see a new technology appear in one’s lifetime and to feel some kind of ownership over it, to see it for what it is or, even more importantly, what it did—how it cut through the world. And since video is, or was, so closely related to television and what used to be called the mass media—it was either its intimate underbelly or a guerrilla weapon made to combat it—its value seemed to go unquestioned. The most important artists wrestled with it (Lynda Benglis, Dara Birnbaum, Nam June Paik, Ulysses Jenkins, Joan Jonas, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson); some of the best writers took it on (David Antin, Allan Kaprow, Rosalind Krauss, Anne Wagner). But when television went from a weekly calendar to a massive database that viewers could scan wherever, whenever, something changed; as video’s hardware flattened out and flooded the world, grafting itself onto automobiles and gas pumps—not to mention phones, bus stops, and airplanes—something gave way. (“In the mid-nineteen sixties people started moving television sets away from the wall,” Gregory Battcock wrote long ago. “The implications of this phenomenon . . . are enormous.”) It was as if every surface in the world had suddenly come throbbingly, pulsingly alive. Production also transformed. If the shift from film camera to Porta-Pak cut down on crew, the leap to phone and personal computer offered advanced editing techniques to almost any amateur—so video changed not only the world’s texture but also how we interact with it.

THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT VIDEO ART that calls for grand theories and epic summations, wild pronouncements and heroic declarations. It’s exciting to see a new technology appear in one’s lifetime and to feel some kind of ownership over it, to see it for what it is or, even more importantly, what it did—how it cut through the world. And since video is, or was, so closely related to television and what used to be called the mass media—it was either its intimate underbelly or a guerrilla weapon made to combat it—its value seemed to go unquestioned. The most important artists wrestled with it (Lynda Benglis, Dara Birnbaum, Nam June Paik, Ulysses Jenkins, Joan Jonas, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson); some of the best writers took it on (David Antin, Allan Kaprow, Rosalind Krauss, Anne Wagner). But when television went from a weekly calendar to a massive database that viewers could scan wherever, whenever, something changed; as video’s hardware flattened out and flooded the world, grafting itself onto automobiles and gas pumps—not to mention phones, bus stops, and airplanes—something gave way. (“In the mid-nineteen sixties people started moving television sets away from the wall,” Gregory Battcock wrote long ago. “The implications of this phenomenon . . . are enormous.”) It was as if every surface in the world had suddenly come throbbingly, pulsingly alive. Production also transformed. If the shift from film camera to Porta-Pak cut down on crew, the leap to phone and personal computer offered advanced editing techniques to almost any amateur—so video changed not only the world’s texture but also how we interact with it.