Travis Elborough at The Paris Review:

It seems no less than highly appropriate that when Ian Nairn’s Modern Buildings in London first appeared in 1964 it was purchasable from one of a hundred automatic book-vending machines that had been installed in a selection of inner-London train stations just two years earlier. Sadly, these machines, operated by the British Automatic Company, were short-lived. Persistent vandalism and theft saw them axed during the so-called Summer of Love, by which time, and perhaps thanks to Doctor Who’s then-recent battles with mechanoid Cybermen, the shine had rather come off the idea of unfettered technological progress. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its malevolent supercomputer HAL 9000, after all, lay only a few months away. And so too, did the partial collapse of the Ronan Point high-rise (a space-age monolith of sorts) in Canning Town, East London—an event widely credited with helping to turn the general public against modernist architecture.

It seems no less than highly appropriate that when Ian Nairn’s Modern Buildings in London first appeared in 1964 it was purchasable from one of a hundred automatic book-vending machines that had been installed in a selection of inner-London train stations just two years earlier. Sadly, these machines, operated by the British Automatic Company, were short-lived. Persistent vandalism and theft saw them axed during the so-called Summer of Love, by which time, and perhaps thanks to Doctor Who’s then-recent battles with mechanoid Cybermen, the shine had rather come off the idea of unfettered technological progress. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, with its malevolent supercomputer HAL 9000, after all, lay only a few months away. And so too, did the partial collapse of the Ronan Point high-rise (a space-age monolith of sorts) in Canning Town, East London—an event widely credited with helping to turn the general public against modernist architecture.

more here.

Ask a cancer researcher what the breakthrough treatment of the decade is, and they’ll tell you CAR T takes the crown. The therapy genetically engineers a person’s own immune cells, turning them into super soldiers that hunt down cancerous blood cells. With astonishing speed, multiple CAR T therapies have

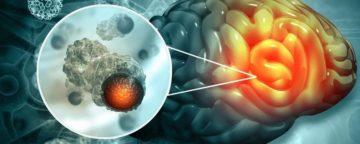

Ask a cancer researcher what the breakthrough treatment of the decade is, and they’ll tell you CAR T takes the crown. The therapy genetically engineers a person’s own immune cells, turning them into super soldiers that hunt down cancerous blood cells. With astonishing speed, multiple CAR T therapies have  Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and malignant form of primary brain cancer. More effective treatments for GBM are direly needed, as the median survival with current therapeutic options is 15 months. One difficulty that scientists face is developing GBM treatments that overcome therapeutic resistance. GBM tumor cells invade the surrounding brain tissue and acquire resistance mediated by factors in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Conventional drug screens that rely on tumor cells grown in culture lack the TME, highlighting the need for better

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and malignant form of primary brain cancer. More effective treatments for GBM are direly needed, as the median survival with current therapeutic options is 15 months. One difficulty that scientists face is developing GBM treatments that overcome therapeutic resistance. GBM tumor cells invade the surrounding brain tissue and acquire resistance mediated by factors in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Conventional drug screens that rely on tumor cells grown in culture lack the TME, highlighting the need for better  I

I I get sentimental about places, especially forgotten ones like Monarch Park. They’re a bit of a bummer, a bit sobering, a bit sad. But I think it’s a good kind of sadness. It’s the kind of sadness that reminds us that life is short: our joy and sorrow are fleeting, the places and people we love are temporary and the extent to which the world will remember us is limited. We don’t like to think about this as human beings. We like to think we’re the main characters of the world’s story, the center of it all, like a 120-foot Electric Tower of light rising high above a magnificent amusement park.

I get sentimental about places, especially forgotten ones like Monarch Park. They’re a bit of a bummer, a bit sobering, a bit sad. But I think it’s a good kind of sadness. It’s the kind of sadness that reminds us that life is short: our joy and sorrow are fleeting, the places and people we love are temporary and the extent to which the world will remember us is limited. We don’t like to think about this as human beings. We like to think we’re the main characters of the world’s story, the center of it all, like a 120-foot Electric Tower of light rising high above a magnificent amusement park. As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s

As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s  On warm summer nights, green lacewings flutter around bright lanterns in backyards and at campsites. The insects, with their veil-like wings, are easily distracted from their natural preoccupation with sipping on flower nectar, avoiding predatory bats and reproducing. Small clutches of the eggs they lay hang from long stalks on the underside of leaves and sway like fairy lights in the wind.

On warm summer nights, green lacewings flutter around bright lanterns in backyards and at campsites. The insects, with their veil-like wings, are easily distracted from their natural preoccupation with sipping on flower nectar, avoiding predatory bats and reproducing. Small clutches of the eggs they lay hang from long stalks on the underside of leaves and sway like fairy lights in the wind. I’m an adult, but my grandmother makes my shirts. The ones with good wicking properties that I wear on my morning runs. Five days per week she sits behind an industrial sewing machine in a room full of them, all cream-colored with metallic details. The machines, that is. The people, mostly women, have shades of brown, resilient skin that has outlived civil war. They rarely giggle. At times, they laugh, eat, go to the bathroom, flirt with ideas, fan themselves with their hands. But for most of the day, they are taciturn, patiently outlasting the drudgery, anticipating evening mass or a phone call from my mother. They aren’t all awaiting my mother’s call. They each have their own daughters. Their sons, however, are dead — a few daughters, too. Not all of them, but enough to dress in black for years. Some of the calls travel long distances. International calls from the United States, mostly. The lucky ones are in Canada — because of the egalitarian policies. The ones who are luckier still are in Vancouver. They ski. Not the daughters, but their children. Skiing is lovely if you can tolerate the ceremony of it all, and the other skiers. My grandmother, however, doesn’t care much for winter sports, even when she’s sewing useful, sometimes clandestine pockets into climate-resistant attire. She cares only about my mother, neat stitches, and, indirectly, about Jesus. She also thinks Richard Dean Anderson, the actor who played MacGyver in the eponymous 1980s television show that was a primetime darling in El Salvador, is a babe. I agreed, but I never said as much. I was eight and visiting my mother’s motherland for only the second time; an admission of that kind would have been about as well received as an incurable retrovirus.

I’m an adult, but my grandmother makes my shirts. The ones with good wicking properties that I wear on my morning runs. Five days per week she sits behind an industrial sewing machine in a room full of them, all cream-colored with metallic details. The machines, that is. The people, mostly women, have shades of brown, resilient skin that has outlived civil war. They rarely giggle. At times, they laugh, eat, go to the bathroom, flirt with ideas, fan themselves with their hands. But for most of the day, they are taciturn, patiently outlasting the drudgery, anticipating evening mass or a phone call from my mother. They aren’t all awaiting my mother’s call. They each have their own daughters. Their sons, however, are dead — a few daughters, too. Not all of them, but enough to dress in black for years. Some of the calls travel long distances. International calls from the United States, mostly. The lucky ones are in Canada — because of the egalitarian policies. The ones who are luckier still are in Vancouver. They ski. Not the daughters, but their children. Skiing is lovely if you can tolerate the ceremony of it all, and the other skiers. My grandmother, however, doesn’t care much for winter sports, even when she’s sewing useful, sometimes clandestine pockets into climate-resistant attire. She cares only about my mother, neat stitches, and, indirectly, about Jesus. She also thinks Richard Dean Anderson, the actor who played MacGyver in the eponymous 1980s television show that was a primetime darling in El Salvador, is a babe. I agreed, but I never said as much. I was eight and visiting my mother’s motherland for only the second time; an admission of that kind would have been about as well received as an incurable retrovirus. Suppose you are considering your career choices. You decide you are going to be a world-leading research scientist. You believe that you are as likely to succeed as anyone else. You are also a young woman. Women are statistically underrepresented in higher level science, and you are aware of countless articles describing structural barriers faced by women in the sciences making it harder for them to reach the higher echelons of the profession. There isn’t anything about your skills or upbringing that gives you reason to think that you are less likely to face these barriers than other women. Nonetheless, because you want to believe that you are as likely to succeed as your male counterparts, you focus your attention on the successes of specific high profile woman scientists, and these successes allow you to believe what you want to.

Suppose you are considering your career choices. You decide you are going to be a world-leading research scientist. You believe that you are as likely to succeed as anyone else. You are also a young woman. Women are statistically underrepresented in higher level science, and you are aware of countless articles describing structural barriers faced by women in the sciences making it harder for them to reach the higher echelons of the profession. There isn’t anything about your skills or upbringing that gives you reason to think that you are less likely to face these barriers than other women. Nonetheless, because you want to believe that you are as likely to succeed as your male counterparts, you focus your attention on the successes of specific high profile woman scientists, and these successes allow you to believe what you want to. There is a tradition of physicists writing popular books that reflect philosophically on what physics can teach us about the human condition. This book is a contribution to the genre. Hossenfelder is a physicist who works on quantum gravity, with a blog that made her known as a gadfly in her field. A previous book took on one of the sacred cows of theoretical physics – the pursuit of beauty in theorizing – and in this book she says that she is going to bring established science to bear on the kinds of questions that ordinary people ask: “people don’t care much whether quantum mechanics is predictable, they want to know whether their own behavior is predictable; … They don’t care much

There is a tradition of physicists writing popular books that reflect philosophically on what physics can teach us about the human condition. This book is a contribution to the genre. Hossenfelder is a physicist who works on quantum gravity, with a blog that made her known as a gadfly in her field. A previous book took on one of the sacred cows of theoretical physics – the pursuit of beauty in theorizing – and in this book she says that she is going to bring established science to bear on the kinds of questions that ordinary people ask: “people don’t care much whether quantum mechanics is predictable, they want to know whether their own behavior is predictable; … They don’t care much Hitler’s skyrocketing rise to power is great data for building our threat models. But Mike Godwin is right: it’s easy to see Hitler everywhere. And if we say “Watch out: this is exactly how Hitler came to power!” once a week, eventually no one will even bother turning their head to look.

Hitler’s skyrocketing rise to power is great data for building our threat models. But Mike Godwin is right: it’s easy to see Hitler everywhere. And if we say “Watch out: this is exactly how Hitler came to power!” once a week, eventually no one will even bother turning their head to look. I’ll tell you a secret about working in a massage parlour: it’s a lot of waiting around, usually late at night. We’d wait, half a dozen of us, in the dressing room as the evening wore on. On edge and exhausted in equal parts, we perched on the low-slung couch, adjusted the straps of our babydolls, listlessly fluffed our hair, ready to spring into action.

I’ll tell you a secret about working in a massage parlour: it’s a lot of waiting around, usually late at night. We’d wait, half a dozen of us, in the dressing room as the evening wore on. On edge and exhausted in equal parts, we perched on the low-slung couch, adjusted the straps of our babydolls, listlessly fluffed our hair, ready to spring into action. PAUL REUBENS, who died on July 30, aged seventy, was not just an American original, entertainer, actor, mischief-maker, and mensch, but a great artist. His most famous creation was, of course, Pee-wee Herman, the adorably bonkers, puppy-dog-eyed anarchist in red bowtie and gray plaid suit who took TV off into a wild and wonderful dreamscape totally beyond anywhere (or anything!) it had been before. A CalArts alumnus (student of Allan Kaprow; classmate of David Hasselhoff), Reubens said, “I always felt [Pee-wee] was conceptual art but no one knew that except me.” Yup, he got right into the Reagan-era mainstream when things were hideous to the max and created all kinds of hallucinogenic chaos. Behold his masterpiece, Pee-wee’s Playhouse (1986–91): At the height of the AIDS crisis, queer royalty came over every Saturday morning: Little Richard! Sandra Bernhard! Grace Jones! His adventures, lair, and pals were wholly innocent and extremely subversive, an outrageous celebration of imagination and otherness run amok at a time when that was severely endangered. No other show (nominally “for kids”) has ever been louder or more delighted about being Art, a simultaneously freaky and extremely heartwarming carnival high on its own psychedelic rollercoaster aesthetics, full of nonstop chaos. It was a neon gift and a gateway drug for tons of kids who grew up to be artists. Gathered below, a mourning chorus of friends, collaborators, and devotees give just a hint of the magical singularity of his talents and influence—and of how deeply he’ll be missed.

PAUL REUBENS, who died on July 30, aged seventy, was not just an American original, entertainer, actor, mischief-maker, and mensch, but a great artist. His most famous creation was, of course, Pee-wee Herman, the adorably bonkers, puppy-dog-eyed anarchist in red bowtie and gray plaid suit who took TV off into a wild and wonderful dreamscape totally beyond anywhere (or anything!) it had been before. A CalArts alumnus (student of Allan Kaprow; classmate of David Hasselhoff), Reubens said, “I always felt [Pee-wee] was conceptual art but no one knew that except me.” Yup, he got right into the Reagan-era mainstream when things were hideous to the max and created all kinds of hallucinogenic chaos. Behold his masterpiece, Pee-wee’s Playhouse (1986–91): At the height of the AIDS crisis, queer royalty came over every Saturday morning: Little Richard! Sandra Bernhard! Grace Jones! His adventures, lair, and pals were wholly innocent and extremely subversive, an outrageous celebration of imagination and otherness run amok at a time when that was severely endangered. No other show (nominally “for kids”) has ever been louder or more delighted about being Art, a simultaneously freaky and extremely heartwarming carnival high on its own psychedelic rollercoaster aesthetics, full of nonstop chaos. It was a neon gift and a gateway drug for tons of kids who grew up to be artists. Gathered below, a mourning chorus of friends, collaborators, and devotees give just a hint of the magical singularity of his talents and influence—and of how deeply he’ll be missed.