Kamran Javadizadeh in The Yale Review:

Ninety-three days before she died, my sister sent me a message. Five and a half years earlier, Bita had been diagnosed with stage four intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a rare and deadly form of cancer. She was forty-three. There was a thirteen-centimeter mass—roughly the size of a grapefruit—in her liver. When the radiologist friend who’d helped get Bita into Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center saw me in the hospital corridor after her diagnosis, he burst into tears.

Ninety-three days before she died, my sister sent me a message. Five and a half years earlier, Bita had been diagnosed with stage four intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, a rare and deadly form of cancer. She was forty-three. There was a thirteen-centimeter mass—roughly the size of a grapefruit—in her liver. When the radiologist friend who’d helped get Bita into Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center saw me in the hospital corridor after her diagnosis, he burst into tears.

Bita had been in treatment ever since; I had been beside her for nearly every appointment. They tended to be on Mondays: I’d take the train from Philadelphia to New York City and meet her in the waiting area of her oncologist’s clinic. Inside, I’d watch and listen and take notes. I discovered I had a talent for explaining to the doctor what my sister wanted to know but was reluctant to ask directly, and for explaining to Bita the implications of what he’d actually said rather than what she was afraid she’d heard. I’m a poetry critic and a teacher. What I did in the oncologist’s clinic was not so different from what I do in the classroom or on the page. I listened and redescribed what I’d heard; I connected threads, or tried to.

More here.

This July has been the hottest in our

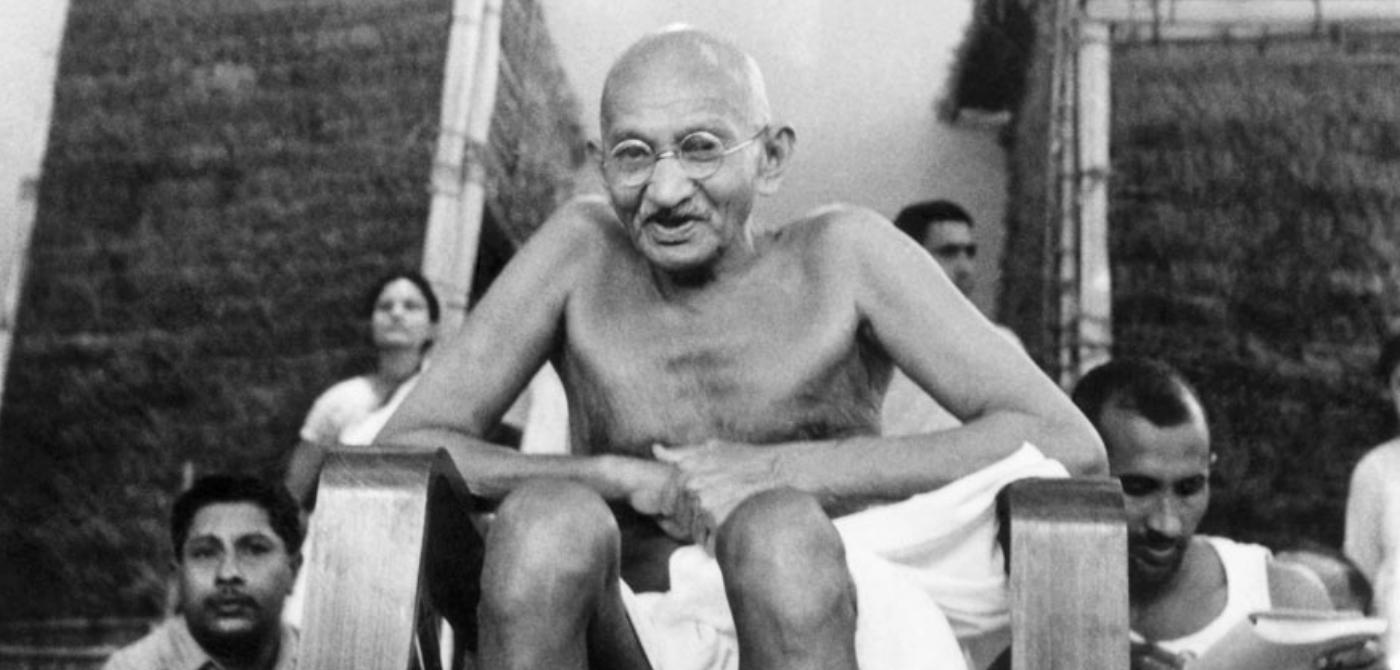

This July has been the hottest in our  I will begin on a self-conscious note. For some years, I have put off writing about Gandhi’s views on caste for my long-gestating book manuscript on Gandhi’s thought. The subject had become so fraught, as a result of recent invectives directed at Gandhi, that I did not trust myself to not get caught up in an ideological maelstrom in which anything one said by way of trying to merely even understand his views would come off as a kind of apologetics, which I had no wish to produce since, for all my admiring interest in him, I am not a Gandhi-bhakt. Indeed, as will emerge in what I am about to say, he is sometimes quite wrong on this subject as, no doubt, on others.

I will begin on a self-conscious note. For some years, I have put off writing about Gandhi’s views on caste for my long-gestating book manuscript on Gandhi’s thought. The subject had become so fraught, as a result of recent invectives directed at Gandhi, that I did not trust myself to not get caught up in an ideological maelstrom in which anything one said by way of trying to merely even understand his views would come off as a kind of apologetics, which I had no wish to produce since, for all my admiring interest in him, I am not a Gandhi-bhakt. Indeed, as will emerge in what I am about to say, he is sometimes quite wrong on this subject as, no doubt, on others. Scotus remains a polarising figure, but his humanist detractors would be horrified to learn that here in the

Scotus remains a polarising figure, but his humanist detractors would be horrified to learn that here in the  In “The Song of Myself”, Whitman tells us “I am the man, I suffered, I was there”. The poetic force of his work, which the American poet James Wright terms his “delicacy”, arises from the exactness of his observations; Whitman’s dedication to what he called “every organ and attribute”. This commitment to specificity is vital in understanding Del Rey’s artistic evolution; in her work on NFR! and beyond, she exhibits an oblique approach to individual experience, one that places a similar emphasis on precision. An instinct for poetic specificity is most apparent on “Blue Bannisters”, “Kintsugi” and “Fingertips”, sprawling, stream-of-consciousness confessionals that speak to Jesus, her family, lovers past and present, the dead and the living and the unborn, America, the Earth and the heavens, herself. There’s a Whitman-esque delicacy to her lyrics, whether they’re about the way John Denver holds the note on “Rocky Mountain High”, her sister making birthday cake while chickens run around the yard, or dropping a location pin to her lover on a hot night in the canyon.

In “The Song of Myself”, Whitman tells us “I am the man, I suffered, I was there”. The poetic force of his work, which the American poet James Wright terms his “delicacy”, arises from the exactness of his observations; Whitman’s dedication to what he called “every organ and attribute”. This commitment to specificity is vital in understanding Del Rey’s artistic evolution; in her work on NFR! and beyond, she exhibits an oblique approach to individual experience, one that places a similar emphasis on precision. An instinct for poetic specificity is most apparent on “Blue Bannisters”, “Kintsugi” and “Fingertips”, sprawling, stream-of-consciousness confessionals that speak to Jesus, her family, lovers past and present, the dead and the living and the unborn, America, the Earth and the heavens, herself. There’s a Whitman-esque delicacy to her lyrics, whether they’re about the way John Denver holds the note on “Rocky Mountain High”, her sister making birthday cake while chickens run around the yard, or dropping a location pin to her lover on a hot night in the canyon. The 2024 presidential election is 14 months away, which means political news sites are already saturated with poll-obsessed prognostication and horse-race reporting. In this way, every election season is alike—but this year’s run-up has felt particularly repetitive. Joe Biden, who reportedly told advisers in 2019 that he

The 2024 presidential election is 14 months away, which means political news sites are already saturated with poll-obsessed prognostication and horse-race reporting. In this way, every election season is alike—but this year’s run-up has felt particularly repetitive. Joe Biden, who reportedly told advisers in 2019 that he  How long can human beings live? Although

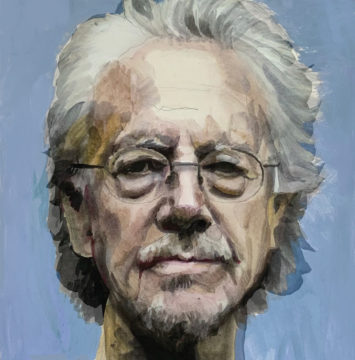

How long can human beings live? Although  Although Handke first came to prominence as a playwright and novelist of prolific output (he’s the author of dozens of works), he has become much better known for his politics. His support for Serbia in the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, particularly his statements about the genocidal violence committed against Bosnian Muslims, has made him a pariah. A habitual contrarian, Handke embraced his outcast status and offered a bizarre disputation of the facts of the war that struck many as delusional, especially considering that he had only a glancing personal interest in Balkan politics—his mother was Slovenian, a fact he clung to with increasing intensity. In the years that followed, Handke has dug in even deeper. When Slobodan Milošević died in 2006 during his trial for war crimes, Handke spoke at his funeral. Years later, he was feted and decorated by the Serbian government. Despite the support of high-profile writers like Elfriede Jelinek and Karl Ove Knausgaard, his reputation has suffered. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2019, protest was widespread and one member of the Nobel committee promptly resigned, in part because of his politics.

Although Handke first came to prominence as a playwright and novelist of prolific output (he’s the author of dozens of works), he has become much better known for his politics. His support for Serbia in the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, particularly his statements about the genocidal violence committed against Bosnian Muslims, has made him a pariah. A habitual contrarian, Handke embraced his outcast status and offered a bizarre disputation of the facts of the war that struck many as delusional, especially considering that he had only a glancing personal interest in Balkan politics—his mother was Slovenian, a fact he clung to with increasing intensity. In the years that followed, Handke has dug in even deeper. When Slobodan Milošević died in 2006 during his trial for war crimes, Handke spoke at his funeral. Years later, he was feted and decorated by the Serbian government. Despite the support of high-profile writers like Elfriede Jelinek and Karl Ove Knausgaard, his reputation has suffered. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2019, protest was widespread and one member of the Nobel committee promptly resigned, in part because of his politics. The goal of this article is to make a lot of this knowledge accessible to a broad audience. We’ll aim to explain what’s known about the inner workings of these models without resorting to technical jargon or advanced math.

The goal of this article is to make a lot of this knowledge accessible to a broad audience. We’ll aim to explain what’s known about the inner workings of these models without resorting to technical jargon or advanced math. Let’s get a few things straight to start with. First, higher education as it currently exists is not going anywhere. There are more than

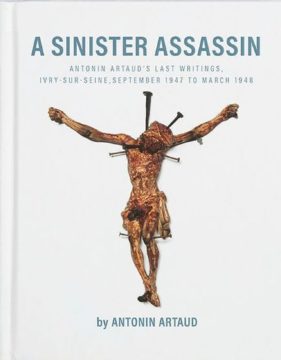

Let’s get a few things straight to start with. First, higher education as it currently exists is not going anywhere. There are more than  AT THE END of his life, the inveterate surrealist Antonin Artaud returned to his notion of a transformative “Theater of Cruelty.” In February 1948, a month before his death, in a famously banned radio broadcast in Paris entitled To Have Done with the Judgment of God, he proclaimed, “Man is ill because he is badly constructed,” announcing a “body without organs” that “will have delivered him from all his automatisms / and returned him to his true liberty.” Artaud saw this last radio work as a “mini-model” of what a Theater of Cruelty could be. Artaud had just emerged from a horrific, nine-year asylum confinement (lasting from September 1937 to May 1946), and the series of radio works were part of a ferocious taking back of his voice and life.

AT THE END of his life, the inveterate surrealist Antonin Artaud returned to his notion of a transformative “Theater of Cruelty.” In February 1948, a month before his death, in a famously banned radio broadcast in Paris entitled To Have Done with the Judgment of God, he proclaimed, “Man is ill because he is badly constructed,” announcing a “body without organs” that “will have delivered him from all his automatisms / and returned him to his true liberty.” Artaud saw this last radio work as a “mini-model” of what a Theater of Cruelty could be. Artaud had just emerged from a horrific, nine-year asylum confinement (lasting from September 1937 to May 1946), and the series of radio works were part of a ferocious taking back of his voice and life.

Tiny

Tiny  In a marked moment near the opening of Joyland—directed by Saim Sadiq and the first Pakistani film to be shortlisted by the Academy Awards—Haider meets Biba in a hospital in Lahore, looking dazed in a blood-splattered shirt. Though this is the first time they’ve met, we’re given no narration, just Haider’s wide-eyed, fascinated gaze. Later, in an intimate moment in her room, Biba tells Haider more about that night: about seeing her friend, also trans

In a marked moment near the opening of Joyland—directed by Saim Sadiq and the first Pakistani film to be shortlisted by the Academy Awards—Haider meets Biba in a hospital in Lahore, looking dazed in a blood-splattered shirt. Though this is the first time they’ve met, we’re given no narration, just Haider’s wide-eyed, fascinated gaze. Later, in an intimate moment in her room, Biba tells Haider more about that night: about seeing her friend, also trans