Shelley Fan in Singularity Hub:

The components sound like the aftermath of a shopping and spa retreat: three AA batteries. Two electrical acupuncture needles. One plastic holder that’s usually attached to battery-powered fairy lights. But together they merge into a powerful stimulation device that uses household batteries to control gene expression in cells.

The idea seems wild, but a new study in Nature Metabolism this week showed that it’s possible. The team, led by Dr. Martin Fussenegger at ETH Zurich and the University of Basel in Switzerland, developed a system that uses direct-current electricity—in the form of batteries or portable battery banks—to turn on a gene in human cells in mice with a literal flip of a switch. To be clear, the battery pack can’t regulate in vivo human genes. For now, it only works for lab-made genes inserted into living cells. Yet the interface has already had an impact. In a proof-of-concept test, the scientists implanted genetically engineered human cells into mice with Type 1 diabetes. These cells are normally silent, but can pump out insulin when activated with an electrical zap.

The idea seems wild, but a new study in Nature Metabolism this week showed that it’s possible. The team, led by Dr. Martin Fussenegger at ETH Zurich and the University of Basel in Switzerland, developed a system that uses direct-current electricity—in the form of batteries or portable battery banks—to turn on a gene in human cells in mice with a literal flip of a switch. To be clear, the battery pack can’t regulate in vivo human genes. For now, it only works for lab-made genes inserted into living cells. Yet the interface has already had an impact. In a proof-of-concept test, the scientists implanted genetically engineered human cells into mice with Type 1 diabetes. These cells are normally silent, but can pump out insulin when activated with an electrical zap.

The team used acupuncture needles to deliver the trigger for 10 seconds a day, and the blood sugar levels in the mice returned to normal within a month. The rodents even regained the ability to manage blood sugar levels after a large meal without the need for external insulin, a normally difficult feat.

Called “electrogenetics,” these interfaces are still in their infancy. But the team is especially excited for their potential in wearables to directly guide therapeutics for metabolic and potentially other disorders. Because the setup requires very little power, three AA batteries could trigger a daily insulin shot for more than five years, they said. The study is the latest to connect the body’s analogue controls—gene expression—with digital and programmable software such as smartphone apps. The system is “a leap forward, representing the missing link that will enable wearables to control genes in the not-so-distant future,” said the team.

More here.

We just want to call everyone’s attention to the rolling nationwide release this week and over the next several (for a complete list of cities and venues see here) of a terrific new film on the life and project of Bobi Wine, the vividly bracing and charismatic Ugandan Afro-pop musician who went from the Kampalan slums to continent-wide celebrity before running afoul of thuggish dictatorial regime of the country’s longtime dictator Museveni (initially by refusing to buckle under to forced-march participation in a music video celebrating the tyrant’s umpteenth presidential run back in 2016). As the regime responded by beginning to forbid his holding concerts in his home country, Wine instead ran for parliament and against all odds won his seat and began flipping other seats by way of his endorsements, till he decided to run himself for president the next time round, in 2020-21, notwithstanding a whole slew of harrowing assassination attempts, arrests and sieges of torture.

We just want to call everyone’s attention to the rolling nationwide release this week and over the next several (for a complete list of cities and venues see here) of a terrific new film on the life and project of Bobi Wine, the vividly bracing and charismatic Ugandan Afro-pop musician who went from the Kampalan slums to continent-wide celebrity before running afoul of thuggish dictatorial regime of the country’s longtime dictator Museveni (initially by refusing to buckle under to forced-march participation in a music video celebrating the tyrant’s umpteenth presidential run back in 2016). As the regime responded by beginning to forbid his holding concerts in his home country, Wine instead ran for parliament and against all odds won his seat and began flipping other seats by way of his endorsements, till he decided to run himself for president the next time round, in 2020-21, notwithstanding a whole slew of harrowing assassination attempts, arrests and sieges of torture.

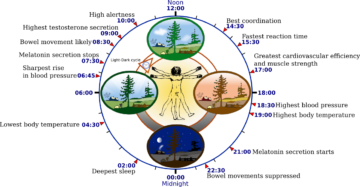

Over the last few years, there has been a groundswell of podcasts, wellness apps and self-improvement social media videos alerting a mass audience to the potential of applying circadian science. It was a

Over the last few years, there has been a groundswell of podcasts, wellness apps and self-improvement social media videos alerting a mass audience to the potential of applying circadian science. It was a In July 1971, the British cybernetician Stafford Beer received an unexpected letter from Chile. Its contents would dramatically change Beer’s life. The writer was a young Chilean engineer named Fernando Flores, who was working for the government of newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende. Flores wrote that he was familiar with Beer’s work in management cybernetics and was “now in a position from which it is possible to implement on a national scale—at which cybernetic thinking becomes a necessity—scientific views on management and organization.” Flores asked Beer for advice on how to apply cybernetics to the management of the nationalized sector of the Chilean economy, which was expanding quickly because of Allende’s aggressive nationalization policy.

In July 1971, the British cybernetician Stafford Beer received an unexpected letter from Chile. Its contents would dramatically change Beer’s life. The writer was a young Chilean engineer named Fernando Flores, who was working for the government of newly elected Socialist president Salvador Allende. Flores wrote that he was familiar with Beer’s work in management cybernetics and was “now in a position from which it is possible to implement on a national scale—at which cybernetic thinking becomes a necessity—scientific views on management and organization.” Flores asked Beer for advice on how to apply cybernetics to the management of the nationalized sector of the Chilean economy, which was expanding quickly because of Allende’s aggressive nationalization policy. People have complicated relationships with hairy skin moles. For some, they symbolize individuality and good fortune. For others, a bothersome blemish. Maksim Plikus, a professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California, Irvine regards these mounds of wild-growing hair as islands of knowledge. His curiosity and astuteness compelled him to look closer at a biological anomaly that others overlooked. “Nothing exists for no reason. There is some really interesting biology hidden in everything,” Plikus said. Skin moles are common growths that contain clusters of melanocytes, the skin’s pigment producing cells. These melanocytes are

People have complicated relationships with hairy skin moles. For some, they symbolize individuality and good fortune. For others, a bothersome blemish. Maksim Plikus, a professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California, Irvine regards these mounds of wild-growing hair as islands of knowledge. His curiosity and astuteness compelled him to look closer at a biological anomaly that others overlooked. “Nothing exists for no reason. There is some really interesting biology hidden in everything,” Plikus said. Skin moles are common growths that contain clusters of melanocytes, the skin’s pigment producing cells. These melanocytes are  The idea seems wild, but

The idea seems wild, but  For over 100 years the cadaver, that unsung hero of murder mysteries, has been accommodating, gracious and generally on time. There is no other figure in crime who has proved more reliable. Since the murder mystery first gained popularity, there have been two world wars, multiple economic crises, dance crazes and moonshots, the advent of radio, cinema, television and the internet. Ideas of right and wrong have evolved, tastes have changed. But through it all, the cadaver has shown up without complaint to do its job. A clock-puncher of the highest order, if you will.

For over 100 years the cadaver, that unsung hero of murder mysteries, has been accommodating, gracious and generally on time. There is no other figure in crime who has proved more reliable. Since the murder mystery first gained popularity, there have been two world wars, multiple economic crises, dance crazes and moonshots, the advent of radio, cinema, television and the internet. Ideas of right and wrong have evolved, tastes have changed. But through it all, the cadaver has shown up without complaint to do its job. A clock-puncher of the highest order, if you will.

I

I It’s tempting to imagine memory as a videotape that stores and plays back the past just as it happened. But the workings of the mind are

It’s tempting to imagine memory as a videotape that stores and plays back the past just as it happened. But the workings of the mind are  Over the past few years, Korean reality TV has been a source of inspiration for my writing. Reading the subtitles is an amazing lesson in dialogue. The random casts of participants are a fun study of group dynamics. These shows allow me to witness tender, precarious moments between lovers and strangers. They prove that the mundane and dramatic often go hand in hand. Watching them, I’ve cried, laughed, and shouted at the screen. I’ve become more aware of how we are all living a life of scenes, surrounded by and involved in a seemingly never-ending narrative.

Over the past few years, Korean reality TV has been a source of inspiration for my writing. Reading the subtitles is an amazing lesson in dialogue. The random casts of participants are a fun study of group dynamics. These shows allow me to witness tender, precarious moments between lovers and strangers. They prove that the mundane and dramatic often go hand in hand. Watching them, I’ve cried, laughed, and shouted at the screen. I’ve become more aware of how we are all living a life of scenes, surrounded by and involved in a seemingly never-ending narrative. I

I  The California State Board of Education’s new math framework, adopted last month, has drawn intense public criticism. Most critics have focused on the framework’s overt political content or its aims to achieve “equity” by holding back advanced students, but there is an arguably even more fundamental problem: an approach to education called inquiry learning, which has virtually zero grounding in research. There is little in the framework that resembles real mathematical learning.

The California State Board of Education’s new math framework, adopted last month, has drawn intense public criticism. Most critics have focused on the framework’s overt political content or its aims to achieve “equity” by holding back advanced students, but there is an arguably even more fundamental problem: an approach to education called inquiry learning, which has virtually zero grounding in research. There is little in the framework that resembles real mathematical learning. Yascha Mounk: You have a really interesting new book called

Yascha Mounk: You have a really interesting new book called  Nearly every step of O’Connor’s career brought trouble. While making her debut album, 1987’s

Nearly every step of O’Connor’s career brought trouble. While making her debut album, 1987’s  T

T