Jyoti Madhusoodanan in Nature:

In August 2021, Amol Akhade, an oncologist at Nair Medical Hospital in Mumbai, India, received an e-mail from the Swiss drug manufacturer Roche recommending the use of a drug named atezolizumab to treat a specific kind of breast cancer. Akhade was surprised. That month, Roche had withdrawn the drug for this purpose in the United States (although it is still approved to treat other kinds of cancer).

In August 2021, Amol Akhade, an oncologist at Nair Medical Hospital in Mumbai, India, received an e-mail from the Swiss drug manufacturer Roche recommending the use of a drug named atezolizumab to treat a specific kind of breast cancer. Akhade was surprised. That month, Roche had withdrawn the drug for this purpose in the United States (although it is still approved to treat other kinds of cancer).

For the type of breast cancer in question — known as triple-negative because it lacks three key protein markers — atezolizumab was made available in 2019 through the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Accelerated Approval Program. Accelerated approval is a fast-track process designed to place desperately needed drugs in the hands of patients quicker than is possible with conventional drug approval. But a follow-up study found that atezolizumab made little difference to tumour growth, and that people who received it were less likely to survive up to two years after treatment than were those not taking it1. When the FDA received these data in 2021, it indicated that accelerated approval was no longer appropriate, and Roche withdrew the drug for this form of breast cancer. The same thing happened with the European Medicines Agency (EMA), based in Amsterdam, but not everywhere else.

In India, for example, where the drug was still approved for triple-negative breast cancer, Roche continued to promote the treatment until at least September, a fact that Akhade says he found “quite shocking”.

More here.

“Streaming” music. Sounds so simple, so peaceful, right? If you’re listening closely, though, you know that contemporary pop is a much choppier body of water, oceanic in its breadth and volume. In little sips and big gulps, I’ll be keeping track of my new faves with the following list of 2023’s best recordings — organized chronologically by release date — and I’ll be updating it continuously throughout the year.

“Streaming” music. Sounds so simple, so peaceful, right? If you’re listening closely, though, you know that contemporary pop is a much choppier body of water, oceanic in its breadth and volume. In little sips and big gulps, I’ll be keeping track of my new faves with the following list of 2023’s best recordings — organized chronologically by release date — and I’ll be updating it continuously throughout the year. F

F Here/After The Art is an attempt to elevate a discussion and research the future of art as it has never been done before. We ask creators to produce NFTs that make predictions on the future of art. This project invites diversity across continents and creative disciplines. For example, in addition to visual artists we will also reach out to renowned filmmakers, musicians, and designers to create a vibrant mix of personalities who have a voice in what art has been, is, and especially what it will be. We recognise and appreciate that all this takes place in the age of emerging technologies including AI, NFT, and in the new spaces such as web3, metaverse and the decentralisation of culture.

Here/After The Art is an attempt to elevate a discussion and research the future of art as it has never been done before. We ask creators to produce NFTs that make predictions on the future of art. This project invites diversity across continents and creative disciplines. For example, in addition to visual artists we will also reach out to renowned filmmakers, musicians, and designers to create a vibrant mix of personalities who have a voice in what art has been, is, and especially what it will be. We recognise and appreciate that all this takes place in the age of emerging technologies including AI, NFT, and in the new spaces such as web3, metaverse and the decentralisation of culture.

Reality is different these days. It isn’t just that we have the tools to experience reality differently, or augment reality, by affixing a Meta Quest headset or an Apple Vision Pro to our skulls. It isn’t just that we have the ability to quantify reality, through smartwatches and heart rate monitors and step counters and sleep trackers, or that we have the ability to manipulate people’s perceptions of reality, through social media filters so ubiquitous that there is now a whole cottage industry of plastic surgery devoted to making people’s fleshly faces match the selfies they post on Instagram. Nor is it just the fact that our social world includes the conversations we have with virtual personal assistants like Siri and Alexa, whose soothing voices greet us when we come home, or remind us of the weather.

Reality is different these days. It isn’t just that we have the tools to experience reality differently, or augment reality, by affixing a Meta Quest headset or an Apple Vision Pro to our skulls. It isn’t just that we have the ability to quantify reality, through smartwatches and heart rate monitors and step counters and sleep trackers, or that we have the ability to manipulate people’s perceptions of reality, through social media filters so ubiquitous that there is now a whole cottage industry of plastic surgery devoted to making people’s fleshly faces match the selfies they post on Instagram. Nor is it just the fact that our social world includes the conversations we have with virtual personal assistants like Siri and Alexa, whose soothing voices greet us when we come home, or remind us of the weather. No audio recordings of Walter Benjamin have survived. His voice was once described as beautiful, even melodious—just the sort of voice that would have been suitable for the new medium of radio broadcasting that spread across Germany in the 1920s. If one could pay the fee for a wireless receiver, Benjamin could be heard in the late afternoons or early evenings, often during what was called “Youth Hour.” His topics ranged widely, from a brass works outside Berlin to a fish market in Naples. In one broadcast, he lavished his attention on an antiquarian bookstore with aisles like labyrinths, whose walls were adorned with drawings of enchanted forests and castles. For others, he related “True Dog Stories” or perplexed his young listeners with brain teasers and riddles. He also wrote, and even acted in, a variety of radio plays that satirized the history of German literature or plunged into surrealist fantasy. One such play introduced a lunar creature named Labu who bore the august title “President of the Moon Committee for Earth Research.”

No audio recordings of Walter Benjamin have survived. His voice was once described as beautiful, even melodious—just the sort of voice that would have been suitable for the new medium of radio broadcasting that spread across Germany in the 1920s. If one could pay the fee for a wireless receiver, Benjamin could be heard in the late afternoons or early evenings, often during what was called “Youth Hour.” His topics ranged widely, from a brass works outside Berlin to a fish market in Naples. In one broadcast, he lavished his attention on an antiquarian bookstore with aisles like labyrinths, whose walls were adorned with drawings of enchanted forests and castles. For others, he related “True Dog Stories” or perplexed his young listeners with brain teasers and riddles. He also wrote, and even acted in, a variety of radio plays that satirized the history of German literature or plunged into surrealist fantasy. One such play introduced a lunar creature named Labu who bore the august title “President of the Moon Committee for Earth Research.” LASTING FOR THREE STRAIGHT DAYS,

LASTING FOR THREE STRAIGHT DAYS, Humans are bioelectrical beings. The collections of cells that make up tissues and organs communicate using the language of voltages and electric fields. This electrical code is produced by specialized ion channels and proteins imbedded in cell membranes.

Humans are bioelectrical beings. The collections of cells that make up tissues and organs communicate using the language of voltages and electric fields. This electrical code is produced by specialized ion channels and proteins imbedded in cell membranes.  M

M When I was a graduate student at the start of the 1990s, I spent half my time thinking about artificial intelligence, especially artificial neural networks, and half my time thinking about consciousness. I’ve ended up working more on consciousness over the years, but over the last decade I’ve keenly followed the explosion of work on deep learning in artificial neural networks. Just recently, my interests in neural networks and in consciousness have begun to collide.

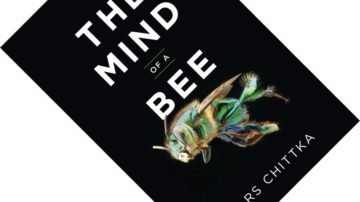

When I was a graduate student at the start of the 1990s, I spent half my time thinking about artificial intelligence, especially artificial neural networks, and half my time thinking about consciousness. I’ve ended up working more on consciousness over the years, but over the last decade I’ve keenly followed the explosion of work on deep learning in artificial neural networks. Just recently, my interests in neural networks and in consciousness have begun to collide. Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Many flowers sport UV patterns invisible to us. Remarkably, UV photoreceptors are found in numerous insects and other crustaceans whose shared ancestry goes back to the Cambrian, predating

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Many flowers sport UV patterns invisible to us. Remarkably, UV photoreceptors are found in numerous insects and other crustaceans whose shared ancestry goes back to the Cambrian, predating

“You know, I don’t really talk to that many other novelists,” James McBride told me. “I don’t spend a lot of time with other writers.” It was a statement that explained a lot, while at the same time shooting a pet theory out of the water. If McBride’s most recent books—the celebrated

“You know, I don’t really talk to that many other novelists,” James McBride told me. “I don’t spend a lot of time with other writers.” It was a statement that explained a lot, while at the same time shooting a pet theory out of the water. If McBride’s most recent books—the celebrated  Petzold has said in interviews that, when he contracted Covid in 2020, he spent weeks watching the films of Eric Rohmer, a French director whose films tell deceptively simple stories, almost fables, and Afire follows this model. The first two acts of the film are essentially a dark comedy of manners: Devid and Felix sleep together, Leon makes fumbling attempts to win Nadja’s affections while offending her and embarrassing himself at every turn. Wildfires are raging in a nearby forest, but our vacationers assure one another that, due to prevailing wind patterns, they are safe from the ongoing devastation—a presumption begging to be challenged.

Petzold has said in interviews that, when he contracted Covid in 2020, he spent weeks watching the films of Eric Rohmer, a French director whose films tell deceptively simple stories, almost fables, and Afire follows this model. The first two acts of the film are essentially a dark comedy of manners: Devid and Felix sleep together, Leon makes fumbling attempts to win Nadja’s affections while offending her and embarrassing himself at every turn. Wildfires are raging in a nearby forest, but our vacationers assure one another that, due to prevailing wind patterns, they are safe from the ongoing devastation—a presumption begging to be challenged. In August 2021, Amol Akhade, an oncologist at Nair Medical Hospital in Mumbai, India, received an e-mail from the Swiss drug manufacturer Roche recommending the use of a drug named atezolizumab to treat a specific kind of breast cancer. Akhade was surprised. That month, Roche had withdrawn the drug for this purpose in the United States (although it is still approved to treat other kinds of cancer).

In August 2021, Amol Akhade, an oncologist at Nair Medical Hospital in Mumbai, India, received an e-mail from the Swiss drug manufacturer Roche recommending the use of a drug named atezolizumab to treat a specific kind of breast cancer. Akhade was surprised. That month, Roche had withdrawn the drug for this purpose in the United States (although it is still approved to treat other kinds of cancer).