Digging

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging, I look down

Till his straining rump among the flower beds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug; the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked,

Loving the cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade

Just like his old man.

My grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away.

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mold, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests

I’ll dig with it.

by Seamus Heaney

from Death of a Naturalist

Faber and Faber, 1966

I am an accidental birder. While I never used to pay much attention to the birds outside my window, even being a bit afraid of them when I was a child, I have always loved making lists. Ranking operas and opera houses, categorising favourite books and beautiful libraries – not to mention decades of creating ‘Top Ten’ lists of hikes, drives, national parks, hotels, and bottles of wine. My birding hobby grew out of this predilection. Specifically, out of my penchant for writing down the birds I found in the paintings by the Old Masters.

I am an accidental birder. While I never used to pay much attention to the birds outside my window, even being a bit afraid of them when I was a child, I have always loved making lists. Ranking operas and opera houses, categorising favourite books and beautiful libraries – not to mention decades of creating ‘Top Ten’ lists of hikes, drives, national parks, hotels, and bottles of wine. My birding hobby grew out of this predilection. Specifically, out of my penchant for writing down the birds I found in the paintings by the Old Masters.

One recalls the days when sympathy was not reduced to a series of yellow crying faces – when people had more time to be human and condolences were not something to be fired off before scrolling on to the next Facebook post.

One recalls the days when sympathy was not reduced to a series of yellow crying faces – when people had more time to be human and condolences were not something to be fired off before scrolling on to the next Facebook post. In 1973 rookie reporter Kevin McKiernan smuggled himself onto the Pine Ridge Sioux Reservation in the trunk of a car, hoping to cover the takeover of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Embedded with activists of the American Indian Movement (AIM)—who clamored for control of their communities and an end to slum conditions, McKiernan filmed their conflicts with Tribal Chair Richard (“Dickie”) Wilson, his armed supporters who called themselves Guardians of Oglala Nation (GOONs), and the government agents backing them. Despite a media blackout, McKiernan sat in on AIM negotiations with the Nixon administration, earning on-camera glares from negotiator Kent Frizzell. As a settlement was hammered out between the groups, McKiernan buried his film in a hole and smuggled himself out of the encampment. Arrests followed, his included. Six weeks later, he returned to Wounded Knee to recover his footage.

In 1973 rookie reporter Kevin McKiernan smuggled himself onto the Pine Ridge Sioux Reservation in the trunk of a car, hoping to cover the takeover of Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Embedded with activists of the American Indian Movement (AIM)—who clamored for control of their communities and an end to slum conditions, McKiernan filmed their conflicts with Tribal Chair Richard (“Dickie”) Wilson, his armed supporters who called themselves Guardians of Oglala Nation (GOONs), and the government agents backing them. Despite a media blackout, McKiernan sat in on AIM negotiations with the Nixon administration, earning on-camera glares from negotiator Kent Frizzell. As a settlement was hammered out between the groups, McKiernan buried his film in a hole and smuggled himself out of the encampment. Arrests followed, his included. Six weeks later, he returned to Wounded Knee to recover his footage. I met Gordon in Phnom Penh a year ago. He had agreed to take me and Ashish Dhakal, a journalist and repatriation activist from Nepal, to Koh Ker and Angkor. First, though, I spent nearly a week at the National Museum of Cambodia. It opened in 1920, designed by George Groslier, to hold the artefacts that archaeologists in French Indochina weren’t shipping back to Paris. He enlarged the architectural forms of Cambodian Buddhist temples to create a building that hadn’t previously been needed in a region where sacred artworks generally remained in place.

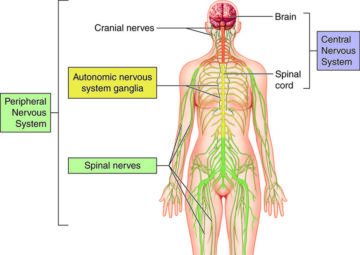

I met Gordon in Phnom Penh a year ago. He had agreed to take me and Ashish Dhakal, a journalist and repatriation activist from Nepal, to Koh Ker and Angkor. First, though, I spent nearly a week at the National Museum of Cambodia. It opened in 1920, designed by George Groslier, to hold the artefacts that archaeologists in French Indochina weren’t shipping back to Paris. He enlarged the architectural forms of Cambodian Buddhist temples to create a building that hadn’t previously been needed in a region where sacred artworks generally remained in place. Multiple sclerosis presents far more variously than most other illnesses; for that reason, it has been called “the great imitator.” Some of the conditions it can resemble are minor, and others are major. If you have ever Googled a random tingling or twinge or eyebrow twitch, you have probably spent at least one evening convinced that you have M.S. On the other hand, M.S. patients often think for a while that they don’t have much going on. One person’s first symptom might be numbness. A different patient might experience weakness. Or an unexplained fall, or fatigue, or difficulty urinating or walking. In the United States, the incidence is around three people in a thousand, which is either rare or common, depending on the emotional heft you ascribe to a third of one per cent of the population.

Multiple sclerosis presents far more variously than most other illnesses; for that reason, it has been called “the great imitator.” Some of the conditions it can resemble are minor, and others are major. If you have ever Googled a random tingling or twinge or eyebrow twitch, you have probably spent at least one evening convinced that you have M.S. On the other hand, M.S. patients often think for a while that they don’t have much going on. One person’s first symptom might be numbness. A different patient might experience weakness. Or an unexplained fall, or fatigue, or difficulty urinating or walking. In the United States, the incidence is around three people in a thousand, which is either rare or common, depending on the emotional heft you ascribe to a third of one per cent of the population. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and Christopher Nolan are known for being beloved by film bros around the world. If Hollywood makes “chick flicks” for women, these directors win prizes for providing what everyone believes to be the opposite thing—a type of film that, interestingly, doesn’t have a catchy, degrading name. (Gloria Steinem once

Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, and Christopher Nolan are known for being beloved by film bros around the world. If Hollywood makes “chick flicks” for women, these directors win prizes for providing what everyone believes to be the opposite thing—a type of film that, interestingly, doesn’t have a catchy, degrading name. (Gloria Steinem once  Neuroscientists, educators and psychologists like Kathy Hirsh-Pasek know that play is as an essential ingredient in the lives of adults as well as children. A weighty and growing body of evidence—spanning evolutionary biology, neuroscience and developmental psychology—has in recent years confirmed the centrality of play to human life. Not only is it a crucial part of childhood development and learning but it is also a means for young and old alike to connect with others and a potent way of supercharging creativity and engagement. Play is so fundamental that neglecting it poses a significant health risk.

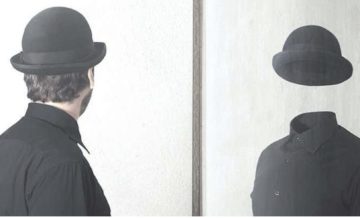

Neuroscientists, educators and psychologists like Kathy Hirsh-Pasek know that play is as an essential ingredient in the lives of adults as well as children. A weighty and growing body of evidence—spanning evolutionary biology, neuroscience and developmental psychology—has in recent years confirmed the centrality of play to human life. Not only is it a crucial part of childhood development and learning but it is also a means for young and old alike to connect with others and a potent way of supercharging creativity and engagement. Play is so fundamental that neglecting it poses a significant health risk. For most ordinary people, it is assumed that “we” exist somewhere within the skull, and this self is free to make decisions. This self is the “captain” of the body, controlling our behaviors and making our life choices. The problem is that neither this inner self nor free will exists the way most think that it does. Research conclusively demonstrates that these are just stories that we humans make up. Michael Gazzaniga’s groundbreaking research eventually concludes that the self is just a fiction created by the brain. Humans make up such stories, believe in them, and rarely question their validity. However, this isn’t the bad news it may appear to be. It is good news, but it will take a while to grasp.

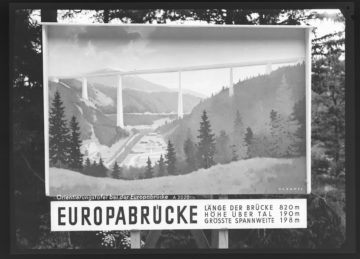

For most ordinary people, it is assumed that “we” exist somewhere within the skull, and this self is free to make decisions. This self is the “captain” of the body, controlling our behaviors and making our life choices. The problem is that neither this inner self nor free will exists the way most think that it does. Research conclusively demonstrates that these are just stories that we humans make up. Michael Gazzaniga’s groundbreaking research eventually concludes that the self is just a fiction created by the brain. Humans make up such stories, believe in them, and rarely question their validity. However, this isn’t the bad news it may appear to be. It is good news, but it will take a while to grasp. Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry.

Before pondering the locations of action cinema (and thus the vectors of our own nostalgias and aspirations), let us briefly rehearse the mystique of Tom Cruise’s action-hero Method-acting, and its storied relationship to cinema as art and industry. Palantir’s founding team, led by investor Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, wanted to create a company capable of using new data integration and data analytics technology — some of it developed to fight online payments fraud — to solve problems of law enforcement, national security, military tactics, and warfare. They called it Palantir, after the magical stones in The Lord of the Rings. Palantir, founded in 2003, developed its tools fighting terrorism after September 11, and has done extensive work for government agencies and corporations though much of its work is secret. It went

Palantir’s founding team, led by investor Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, wanted to create a company capable of using new data integration and data analytics technology — some of it developed to fight online payments fraud — to solve problems of law enforcement, national security, military tactics, and warfare. They called it Palantir, after the magical stones in The Lord of the Rings. Palantir, founded in 2003, developed its tools fighting terrorism after September 11, and has done extensive work for government agencies and corporations though much of its work is secret. It went  There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

One can’t help but feel a sense of wonder reading about the bar-tailed godwit, a bird the size of a football, whose winter migration can take it from Alaska to New Zealand in one marathon flight across the Pacific Ocean. The ornithologists who’ve helped us understand the phenomenon of migration inspire wonder as well. Their ingenuity and zeal are at the heart of Rebecca Heisman’s delightful debut, “Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.”

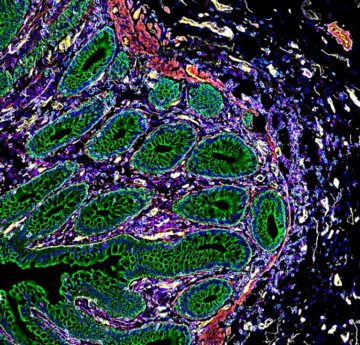

One can’t help but feel a sense of wonder reading about the bar-tailed godwit, a bird the size of a football, whose winter migration can take it from Alaska to New Zealand in one marathon flight across the Pacific Ocean. The ornithologists who’ve helped us understand the phenomenon of migration inspire wonder as well. Their ingenuity and zeal are at the heart of Rebecca Heisman’s delightful debut, “Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration.” Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature

Detailed maps of the cells in human organs show how the placenta commandeers the maternal blood supply, how kidney cells transition from healthy to diseased states and how cells in the intestine organize themselves into distinct neighbourhoods. These atlases, published on 19 July in Nature