From Lapham’s Quarterly:

Writing to his uncle from quarantine in Rhodes, a twenty-eight-year-old Gustave Flaubert complained of the graffiti he had seen on Pompey’s pillar in Alexandria: an Englishman’s name carved in block letters. What right, Flaubert grumbled, did this man have to insert himself into other travelers’ experiences of the column? “Have you sometimes reflected, old uncle, on the limitless serenity of fools?” wrote the young novelist-to-be. “Stupidity is immovable…It has the nature of granite, hard and resistant.” According to him, the graffiti turned Pompey’s pillar into a monument not only to the Roman emperor Diocletian’s victory over a would-be usurper, but also to the foolishness of the public.

Writing to his uncle from quarantine in Rhodes, a twenty-eight-year-old Gustave Flaubert complained of the graffiti he had seen on Pompey’s pillar in Alexandria: an Englishman’s name carved in block letters. What right, Flaubert grumbled, did this man have to insert himself into other travelers’ experiences of the column? “Have you sometimes reflected, old uncle, on the limitless serenity of fools?” wrote the young novelist-to-be. “Stupidity is immovable…It has the nature of granite, hard and resistant.” According to him, the graffiti turned Pompey’s pillar into a monument not only to the Roman emperor Diocletian’s victory over a would-be usurper, but also to the foolishness of the public.

More here.

Sixty years ago, in the summer of 1963, a four-story townhouse on West 130th Street in Harlem became the headquarters for what was then the largest civil rights event in American history, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For one summer the house, a former home for “

Sixty years ago, in the summer of 1963, a four-story townhouse on West 130th Street in Harlem became the headquarters for what was then the largest civil rights event in American history, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For one summer the house, a former home for “ The Moshiach came to Madison Avenue this summer. All over a not particularly Jewish neighborhood, posters of the bearded, Rembrandtesque Rebbe Schneerson appeared, mucilaged to every light post and bearing the caption “Long Live the Lubavitcher Rebbe King Messiah forever!” This was, or ought to have been, trebly astonishing. First, the rebbe being urged to a longer life died in 1994, and the new insistence that he was nonetheless the Moshiach skirted, as his followers tend to do, the question of whether he might remain somehow alive. Second, the very concept of a messiah recapitulates a specific national hope of a small and oft-defeated nation several thousand years ago, and spoke originally to the local Judaean dream of a warrior who would lead his people to victory over the Persians, the Greeks, and, latterly, the Roman colonizers. And, third, the disputes surrounding the rebbe from Crown Heights are strikingly similar to those which surrounded the rebbe Yeshua, or Jesus, when his followers first pressed his claim: was this messianic pretension a horrific blasphemy or a final fulfillment? Yet there it was, another Jewish messiah, on a poster, in 2023.

The Moshiach came to Madison Avenue this summer. All over a not particularly Jewish neighborhood, posters of the bearded, Rembrandtesque Rebbe Schneerson appeared, mucilaged to every light post and bearing the caption “Long Live the Lubavitcher Rebbe King Messiah forever!” This was, or ought to have been, trebly astonishing. First, the rebbe being urged to a longer life died in 1994, and the new insistence that he was nonetheless the Moshiach skirted, as his followers tend to do, the question of whether he might remain somehow alive. Second, the very concept of a messiah recapitulates a specific national hope of a small and oft-defeated nation several thousand years ago, and spoke originally to the local Judaean dream of a warrior who would lead his people to victory over the Persians, the Greeks, and, latterly, the Roman colonizers. And, third, the disputes surrounding the rebbe from Crown Heights are strikingly similar to those which surrounded the rebbe Yeshua, or Jesus, when his followers first pressed his claim: was this messianic pretension a horrific blasphemy or a final fulfillment? Yet there it was, another Jewish messiah, on a poster, in 2023. Everyone knows about the importance of a good night’s sleep. Researchers have also shown the harmful effects of prolonged

Everyone knows about the importance of a good night’s sleep. Researchers have also shown the harmful effects of prolonged  I mean it as a compliment when I say many of the stories in The Islands are disturbing. Shame and alienation are the baggage Irving’s characters carry. Some are entitled, living the American dream, while others scrape by or are haunted by loss. “All-Inclusive” is a gorgeously dark story. In an ironic switch, Anaya, a Los Angeles model-slash-waitress and the daughter of Jamaican immigrants, meets a white man known as The Poet who is from Jamaica. Anaya becomes The Poet’s mistress, and they travel the world together. He is rich, she is poor; he is married, she is not. She revels in being able to “demand drinks, not deliver them,” and “To call for a bed to be turned down.” Anaya hasn’t visited Jamaica since she was a child, and her memories of the place are unpleasant. When she and The Poet take a trip to an all-inclusive resort on the island, Anaya wonders, had she been born and raised in Jamaica, if she would be doing the bidding of thoughtless white tourists, turning down their beds at night. She is ashamed and humbled by being waited on by people like herself and her family, many of whom still live on the island; that she is being willingly used by a white man who disgusts her is a truth she can’t admit to herself until he flat-out tells her. There are no happy endings in The Islands, and redemption is just out of reach. Its characters walk a tightrope between past and present realities.

I mean it as a compliment when I say many of the stories in The Islands are disturbing. Shame and alienation are the baggage Irving’s characters carry. Some are entitled, living the American dream, while others scrape by or are haunted by loss. “All-Inclusive” is a gorgeously dark story. In an ironic switch, Anaya, a Los Angeles model-slash-waitress and the daughter of Jamaican immigrants, meets a white man known as The Poet who is from Jamaica. Anaya becomes The Poet’s mistress, and they travel the world together. He is rich, she is poor; he is married, she is not. She revels in being able to “demand drinks, not deliver them,” and “To call for a bed to be turned down.” Anaya hasn’t visited Jamaica since she was a child, and her memories of the place are unpleasant. When she and The Poet take a trip to an all-inclusive resort on the island, Anaya wonders, had she been born and raised in Jamaica, if she would be doing the bidding of thoughtless white tourists, turning down their beds at night. She is ashamed and humbled by being waited on by people like herself and her family, many of whom still live on the island; that she is being willingly used by a white man who disgusts her is a truth she can’t admit to herself until he flat-out tells her. There are no happy endings in The Islands, and redemption is just out of reach. Its characters walk a tightrope between past and present realities. Perhaps, to begin with, a remark by Nabokov—always a good place to start—who at the time was laying out the requisites for being a good novelist, though, for our purposes we might think of these as the requirements for being fully alive. But listen to him closely, because it’s the opposite of how we usually think of these things: “The true master,” he says, “requires, the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist.” The precision of a poet—and the imagination of a scientist.

Perhaps, to begin with, a remark by Nabokov—always a good place to start—who at the time was laying out the requisites for being a good novelist, though, for our purposes we might think of these as the requirements for being fully alive. But listen to him closely, because it’s the opposite of how we usually think of these things: “The true master,” he says, “requires, the precision of a poet and the imagination of a scientist.” The precision of a poet—and the imagination of a scientist. It’s hard to know how to review a Morgan Meis book, and the more books he writes, the harder it gets. That is, I think, precisely the point. Meis’s last book, The Drunken Silenus (part one of the Three Paintings trilogy, published by Slant Books), tackles the question “What is the best thing for man?”, knocks it flat, and gives it a concussion. Part two of the trilogy, The Fate of the Animals, is the tale of a painting whose artist thought it was almost unseeable, is enamored of the unsayable—yet by the final page, Meis has come terrifying close to saying just that.

It’s hard to know how to review a Morgan Meis book, and the more books he writes, the harder it gets. That is, I think, precisely the point. Meis’s last book, The Drunken Silenus (part one of the Three Paintings trilogy, published by Slant Books), tackles the question “What is the best thing for man?”, knocks it flat, and gives it a concussion. Part two of the trilogy, The Fate of the Animals, is the tale of a painting whose artist thought it was almost unseeable, is enamored of the unsayable—yet by the final page, Meis has come terrifying close to saying just that. AI’s contributions to research and development might help to solve some of humanity’s oldest challenges, including by finding new treatments for diseases. The patent system must be overhauled.

AI’s contributions to research and development might help to solve some of humanity’s oldest challenges, including by finding new treatments for diseases. The patent system must be overhauled. The concept of “elite overproduction” has attracted a lot of attention in the past several years, and it’s not hard to see why. Most associated with Peter Turchin, a researcher who has attempted to develop models that describe and predict the flow of history, elite overproduction refers to periods during which societies generate more members of elite classes than the society can grant elite privileges. Turchin argues that these periods often produce social unrest, as the resentful elites jostle for the advantages to which they believe they’re entitled.

The concept of “elite overproduction” has attracted a lot of attention in the past several years, and it’s not hard to see why. Most associated with Peter Turchin, a researcher who has attempted to develop models that describe and predict the flow of history, elite overproduction refers to periods during which societies generate more members of elite classes than the society can grant elite privileges. Turchin argues that these periods often produce social unrest, as the resentful elites jostle for the advantages to which they believe they’re entitled. D

D A

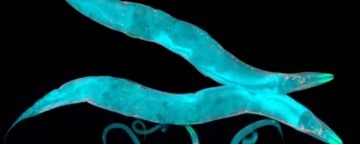

A Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced  I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is).

I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is).  There are two

There are two