Laith Al-Shawaf at Areo:

If you infect a rabbit with a virus or a bacterium, it’ll start to run a fever. Why? The surprising answer is that fever is not a disease; it’s a defence: a useful evolved mechanism that animals use to kill invading pathogens. Studies show that if you give fever-suppressing drugs to infected rabbits, they’re more likely to die.

If you infect a rabbit with a virus or a bacterium, it’ll start to run a fever. Why? The surprising answer is that fever is not a disease; it’s a defence: a useful evolved mechanism that animals use to kill invading pathogens. Studies show that if you give fever-suppressing drugs to infected rabbits, they’re more likely to die.

It’s not just rabbits—all warm-blooded creatures use fever to kill invasive parasites. Animals that can’t regulate their body temperature internally take a different approach. For example, infected lizards seek a hot rock on which to sunbathe, raising their body temperature and killing the invaders that way—and research shows that disrupting their ability to do this increases their likelihood of death. Infected fish and reptiles exhibit this kind of “behavioural fever,” too. In humans, some studies find that administering fever-suppressing drugs to children may worsen outcomes and prolong the period of illness.

These findings suggest that fever is not a symptom of a disease; it’s an evolved defence that our bodies use to kill harmful invaders. Discoveries like this represent one small part of a larger picture emerging from the new science of evolutionary medicine. There’s a scientific revolution brewing, catalysed by the idea that considering how our bodies evolved will help us better understand and treat disease.

More here.

I have never told this story in its entirety to anyone: not to my therapist, not to my closest friends, and not even to my family. I’ve divulged bits and pieces of it to different people. When my friends back home in Iran asked me why I was leaving, I made up a thousand different reasons. When my friends in Istanbul asked me what happened and why I came, I said that a part of me had died, that my ambition, courage, and hope for the future had dried up. But I didn’t explain why. I couldn’t connect the single moments into a coherent narrative.

I have never told this story in its entirety to anyone: not to my therapist, not to my closest friends, and not even to my family. I’ve divulged bits and pieces of it to different people. When my friends back home in Iran asked me why I was leaving, I made up a thousand different reasons. When my friends in Istanbul asked me what happened and why I came, I said that a part of me had died, that my ambition, courage, and hope for the future had dried up. But I didn’t explain why. I couldn’t connect the single moments into a coherent narrative. WHEN A DEER, A DOE, STEPPED INTO THE ROAD perhaps a hundred and twenty feet ahead of the car I was driving, it seemed for a moment that she would die, even though, during the same moment, I did not feel afraid that I would hit her. I was calm; I returned my smoking hand to the steering wheel; I braked. The deer seemed to be looking at me. There was a chance she might actually run toward me. I switched off the high-beams. All of this happened in two and a half seconds, before the deer continued across the road, safely to the other side, in a single bound. It was then that, exhaling, I realized the extent to which I had felt for—on behalf of—the animal, and for days after I dwelled on the feeling.

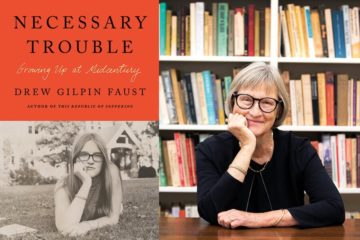

WHEN A DEER, A DOE, STEPPED INTO THE ROAD perhaps a hundred and twenty feet ahead of the car I was driving, it seemed for a moment that she would die, even though, during the same moment, I did not feel afraid that I would hit her. I was calm; I returned my smoking hand to the steering wheel; I braked. The deer seemed to be looking at me. There was a chance she might actually run toward me. I switched off the high-beams. All of this happened in two and a half seconds, before the deer continued across the road, safely to the other side, in a single bound. It was then that, exhaling, I realized the extent to which I had felt for—on behalf of—the animal, and for days after I dwelled on the feeling. Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir is both a moving personal narrative and an enlightening account of the transformative political and social forces that impacted her as she came of age in the 1950s and ’60s. It’s an apt combination from an acclaimed historian who’s also a powerful storyteller.

Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir is both a moving personal narrative and an enlightening account of the transformative political and social forces that impacted her as she came of age in the 1950s and ’60s. It’s an apt combination from an acclaimed historian who’s also a powerful storyteller. When the diabetes treatments known as GLP-1 analogs reached the market in 2005, doctors advised patients taking the drugs that they might lose a small amount of weight. Talk about an understatement. Obese people can drop more than 15% of their body weight, studies have found, and two of the medications are now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight reduction. A surge in demand for the drugs as slimming treatments has led to shortages. “This class of drugs is exploding in popularity,” says clinical psychologist Joseph Schacht of the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

When the diabetes treatments known as GLP-1 analogs reached the market in 2005, doctors advised patients taking the drugs that they might lose a small amount of weight. Talk about an understatement. Obese people can drop more than 15% of their body weight, studies have found, and two of the medications are now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight reduction. A surge in demand for the drugs as slimming treatments has led to shortages. “This class of drugs is exploding in popularity,” says clinical psychologist Joseph Schacht of the University of Colorado School of Medicine. In 1995, there weren’t many foreign tourists in the country. It was a year after the United States normalized relations with Hanoi and lifted sanctions. Most of the passengers on the flight to Hồ Chí Minh City were Việt kiều, visiting their country for the first time since they left. The tension they felt as they cleared customs was obvious.

In 1995, there weren’t many foreign tourists in the country. It was a year after the United States normalized relations with Hanoi and lifted sanctions. Most of the passengers on the flight to Hồ Chí Minh City were Việt kiều, visiting their country for the first time since they left. The tension they felt as they cleared customs was obvious. In Germany they joke that Slavs live in poverty so they can drive home in a Mercedes. I hadn’t heard this stereotype growing up in so-called Australia. From there, we had to fly.

In Germany they joke that Slavs live in poverty so they can drive home in a Mercedes. I hadn’t heard this stereotype growing up in so-called Australia. From there, we had to fly.

Sometimes words explode. It is a safe bet that, before 2022, you had never even heard the term ‘polycrisis’. Now, there is a very good chance you have run into it; and, if you are engaged in environmental, economic or security issues, you most likely have – you might even have become frustrated with it. First virtually nobody was using polycrisis talk, and suddenly everyone seems

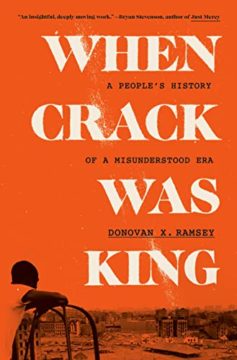

Sometimes words explode. It is a safe bet that, before 2022, you had never even heard the term ‘polycrisis’. Now, there is a very good chance you have run into it; and, if you are engaged in environmental, economic or security issues, you most likely have – you might even have become frustrated with it. First virtually nobody was using polycrisis talk, and suddenly everyone seems  Hiding in plain sight, the largely unexamined crack epidemic of the 1980s and early 1990s has much to teach us about current US drug policy, the blatant racism of drug-related sentencing, and the power of community action. In his important, balanced book

Hiding in plain sight, the largely unexamined crack epidemic of the 1980s and early 1990s has much to teach us about current US drug policy, the blatant racism of drug-related sentencing, and the power of community action. In his important, balanced book  The tiny forest lives atop an old landfill in the city of Cambridge, Mass. Though it is still a baby, it’s already acting quite a bit older than its actual age, which is just shy of 2. Its aspens are growing at twice the speed normally expected, with fragrant sumac and tulip trees racing to catch up. It has absorbed storm water without washing out, suppressed many weeds and stayed lush throughout last year’s drought. The little forest managed all this because of its enriched soil and density, and despite its diminutive size: 1,400 native shrubs and saplings, thriving in an area roughly the size of a basketball court.

The tiny forest lives atop an old landfill in the city of Cambridge, Mass. Though it is still a baby, it’s already acting quite a bit older than its actual age, which is just shy of 2. Its aspens are growing at twice the speed normally expected, with fragrant sumac and tulip trees racing to catch up. It has absorbed storm water without washing out, suppressed many weeds and stayed lush throughout last year’s drought. The little forest managed all this because of its enriched soil and density, and despite its diminutive size: 1,400 native shrubs and saplings, thriving in an area roughly the size of a basketball court.

Advait Arun in Phenomenal World:

Advait Arun in Phenomenal World: