Samantha Harvey in The Guardian:

All our body wants is to sleep, it wants to leave us, head back to the stable, a worn-out horse,” writes Marie Darrieussecq, at which I, a worn-out human, think yes. In a recent interview, Darrieussecq reflected on how much of her work is concerned with inhabiting. Who has a right to inhabit this planet, she asks, and who doesn’t? Though she was talking about her novel Crossed Lines, in which a Parisian woman finds her life becoming bound up with that of a young Nigerian refugee, she could just as well be referring to Sleepless (Pas Dormir in the original French), a book that is – what? A memoir/interrogation/painting/song of insomnia, her own and that of others. It’s a book about where, why, how we sleep and don’t sleep; about how to find a place in the world where sleep can happen, a stable for the worn-out horse.

All our body wants is to sleep, it wants to leave us, head back to the stable, a worn-out horse,” writes Marie Darrieussecq, at which I, a worn-out human, think yes. In a recent interview, Darrieussecq reflected on how much of her work is concerned with inhabiting. Who has a right to inhabit this planet, she asks, and who doesn’t? Though she was talking about her novel Crossed Lines, in which a Parisian woman finds her life becoming bound up with that of a young Nigerian refugee, she could just as well be referring to Sleepless (Pas Dormir in the original French), a book that is – what? A memoir/interrogation/painting/song of insomnia, her own and that of others. It’s a book about where, why, how we sleep and don’t sleep; about how to find a place in the world where sleep can happen, a stable for the worn-out horse.

Sleepless isn’t a book that’s straightforward to convey, at least not briefly.

More here.

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced

Every organism responds to the world with an intricate cascade of biochemistry. There’s a source of heat here, a faint scent of food there, or the crack of a twig as something moves nearby. Each stimulus can trigger the rise of one set of molecules in an animal’s body and perhaps the fall of others. The effect ramifies, tripping feedback loops and flipping switches, until a bird leaps into the air or a bee alights on a flower. It’s a vision of biology that entranced  I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is).

I wanted to write a poem about how the extreme heat of the ocean is breaking my heart, but the whales beat me to it. In late July, almost 100 long-finned pilot whales left the deep, usually cold waters where they live—so deep, so cold that scientists have barely been able to study them. Together they came to the coast of western Australia and huddled into a massive heart shape (if your heart were shaped like 100 black whales, like mine is).  There are two

There are two What would a successful war novel look like? This question, asked of a teacher years ago, concealed a deeper question I had: What would a truthful Kashmir novel look like? I have grappled for years with such questions, since I grew up amid the violent rebellion that Kashmiri Muslims waged against the Indian state in 1988. At first, I wondered whether the job of the novelist was to replicate the traumatic event that one had intimately witnessed.

What would a successful war novel look like? This question, asked of a teacher years ago, concealed a deeper question I had: What would a truthful Kashmir novel look like? I have grappled for years with such questions, since I grew up amid the violent rebellion that Kashmiri Muslims waged against the Indian state in 1988. At first, I wondered whether the job of the novelist was to replicate the traumatic event that one had intimately witnessed. Though Weil coined the term decreation, she never treated it at length in a single text. Instead, she seeds passages on the subject through her later notebooks, not living long enough to give them shape. (Depending on your perspective, Thibon helpfully or misleadingly grouped several of these passages under the rubric of “Décréation” in Gravity and Grace.) But honestly, how much more she could have said about this claim? There are only so many ways to express the thought that I should unmake the being who is expressing that same thought. I have read and written a good deal on Weil’s work and life, but the passages on decreation still shock me. They are steeped in Christian imagery and ideals, and I sometimes wonder if my reaction to them has to do with the fact that I am neither a Christian nor religious. (Besides, I know Christians who, like me, are just as stunned by these fragments.) And my shock is not, I believe, because I do not accept a transcendental reality. Instead, I am shocked because her notion of decreation questions not just how I have lived my life but why I should have ever bothered to live in the first place—other than, that is, to surrender my life as quickly and gladly as possible. “Our existence,” she observes matter-of-factly, “is made up only of his waiting for our acceptance of not being.”

Though Weil coined the term decreation, she never treated it at length in a single text. Instead, she seeds passages on the subject through her later notebooks, not living long enough to give them shape. (Depending on your perspective, Thibon helpfully or misleadingly grouped several of these passages under the rubric of “Décréation” in Gravity and Grace.) But honestly, how much more she could have said about this claim? There are only so many ways to express the thought that I should unmake the being who is expressing that same thought. I have read and written a good deal on Weil’s work and life, but the passages on decreation still shock me. They are steeped in Christian imagery and ideals, and I sometimes wonder if my reaction to them has to do with the fact that I am neither a Christian nor religious. (Besides, I know Christians who, like me, are just as stunned by these fragments.) And my shock is not, I believe, because I do not accept a transcendental reality. Instead, I am shocked because her notion of decreation questions not just how I have lived my life but why I should have ever bothered to live in the first place—other than, that is, to surrender my life as quickly and gladly as possible. “Our existence,” she observes matter-of-factly, “is made up only of his waiting for our acceptance of not being.” Deep in a Russian forest, in a well-concealed hermit’s cave, the lone occupant, who hadn’t spoken to another human being for seven years, a hermit named Sergius who had renounced the world, is forced to resist the wiles of a worldly woman who has come to seduce him and almost succeeds had he not, Tolstoy tells us, forfended her intentions by taking an axe and chopping off one of his fingers “below the second joint.”

Deep in a Russian forest, in a well-concealed hermit’s cave, the lone occupant, who hadn’t spoken to another human being for seven years, a hermit named Sergius who had renounced the world, is forced to resist the wiles of a worldly woman who has come to seduce him and almost succeeds had he not, Tolstoy tells us, forfended her intentions by taking an axe and chopping off one of his fingers “below the second joint.” At the 2021 Australian and US Open tennis championships, all the line judges were replaced by machines. This was, in many ways, inevitable. Not only are these machines far more accurate than any human at calling balls in or out, but they can also be programmed to make their calls in a human-like voice, so as not to disorient the players. It is a little eerie, the disembodied shriek of “Out!” coming from nowhere on the court (at the Australian Open the machines are programmed to speak with an Australian accent). But it is far less irritating than the delays required by challenging incorrect calls, and far more reliable. It takes very little getting used to.

At the 2021 Australian and US Open tennis championships, all the line judges were replaced by machines. This was, in many ways, inevitable. Not only are these machines far more accurate than any human at calling balls in or out, but they can also be programmed to make their calls in a human-like voice, so as not to disorient the players. It is a little eerie, the disembodied shriek of “Out!” coming from nowhere on the court (at the Australian Open the machines are programmed to speak with an Australian accent). But it is far less irritating than the delays required by challenging incorrect calls, and far more reliable. It takes very little getting used to. It was nearing eight o’clock in the evening on December 11, 1981, and the serial killer Stephen Morin was driving the SUV of his latest captive, Margy Palm, north out of San Antonio. Helicopters circled the city and police combed the streets, warning people to stay inside and lock the doors. Morin’s reign of terror was sputtering to a clumsy close after a rare mistake earlier that day. He was suspected of the murder, torture, and in some cases rape of more than 30 women in 9 or 10 states—and most of San Antonio now knew that he was on the loose in its manicured, country-club midst.

It was nearing eight o’clock in the evening on December 11, 1981, and the serial killer Stephen Morin was driving the SUV of his latest captive, Margy Palm, north out of San Antonio. Helicopters circled the city and police combed the streets, warning people to stay inside and lock the doors. Morin’s reign of terror was sputtering to a clumsy close after a rare mistake earlier that day. He was suspected of the murder, torture, and in some cases rape of more than 30 women in 9 or 10 states—and most of San Antonio now knew that he was on the loose in its manicured, country-club midst. Russell Moore, editor-in-chief of Christianity Today and a former stalwart of the American Baptist church, said during an interview this month that

Russell Moore, editor-in-chief of Christianity Today and a former stalwart of the American Baptist church, said during an interview this month that  It took 10 years, around 500 scientists and some €600 million, and now the Human Brain Project — one of the biggest research endeavours ever funded by the European Union — is coming to an end. Its audacious goal was to understand the human brain by modelling it in a computer. During its run, scientists under the umbrella of the Human Brain Project (HBP) have published thousands of papers and made significant strides in neuroscience, such as creating detailed 3D maps of at least 200 brain regions

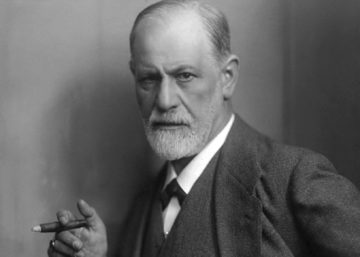

It took 10 years, around 500 scientists and some €600 million, and now the Human Brain Project — one of the biggest research endeavours ever funded by the European Union — is coming to an end. Its audacious goal was to understand the human brain by modelling it in a computer. During its run, scientists under the umbrella of the Human Brain Project (HBP) have published thousands of papers and made significant strides in neuroscience, such as creating detailed 3D maps of at least 200 brain regions Lear is not to first to link the question of whether or not to mourn to speculation about the nature of value. Here, he traces that connection to a 1915 essay by Sigmund Freud, “On Transience,” that marks a second, if still somehow cryptic, focus of Imagining the End. Freud begins his essay by recounting a conversation in the Alpine countryside with a “young poet” who startled him by refusing to take pleasure in the beauties of the landscape because, he said, they are fleeting. Freud responded with the equally extreme assertion that “transience” is the source of all value. By the close of the essay, however, writing from what he now reveals are the depths of a devastating world war, Freud has adopted a chastened view. Unlike the poet, in whom he found a fear of the pain of mourning so great that it barred all attachment, Freud’s hope now, transcending the earlier dichotomy, is that what war has destroyed may one day be rebuilt, not eternally, but “perhaps on more solid ground and more enduringly than before.”

Lear is not to first to link the question of whether or not to mourn to speculation about the nature of value. Here, he traces that connection to a 1915 essay by Sigmund Freud, “On Transience,” that marks a second, if still somehow cryptic, focus of Imagining the End. Freud begins his essay by recounting a conversation in the Alpine countryside with a “young poet” who startled him by refusing to take pleasure in the beauties of the landscape because, he said, they are fleeting. Freud responded with the equally extreme assertion that “transience” is the source of all value. By the close of the essay, however, writing from what he now reveals are the depths of a devastating world war, Freud has adopted a chastened view. Unlike the poet, in whom he found a fear of the pain of mourning so great that it barred all attachment, Freud’s hope now, transcending the earlier dichotomy, is that what war has destroyed may one day be rebuilt, not eternally, but “perhaps on more solid ground and more enduringly than before.” THRALL IS A JEFFERSONIAN WORD. In Constructing a Nervous System, the critic Margo Jefferson is enthralled by or to: her mother, her father, Bing Crosby. She suspects Condoleezza Rice is enthralled by or to George W. Bush, and Ike Turner by or to “manic depression and drug addiction, to years of envy, . . . to a Mississippi childhood that was a trifecta of domestic abuse, sexual treachery and racist violence.” A young James Baldwin enthralled the Harlem faithful. Nina Simone refused the thrall of “warring desires.” It’s the last that clarifies the stakes. Thrall, some time after it meant “slave” to Northern Europeans, found a new Gothic use. Dracula, through hypnosis and sheer erotic power, holds his servants and whole towns in his thrall, the better to protect him while he hides from the sun. Those enthralled submit totally, pleasurably. Influence doesn’t always have to provoke anxiety. There is danger of losing oneself, of being absorbed by the force of another’s will and gaze and magnetism, and that’s before they seize upon your neck. But there’s a reason Dracula persists. Beneath our regimens of self-help, self-care, and self-improvement, we might think briefly of annihilation and find it sweet.

THRALL IS A JEFFERSONIAN WORD. In Constructing a Nervous System, the critic Margo Jefferson is enthralled by or to: her mother, her father, Bing Crosby. She suspects Condoleezza Rice is enthralled by or to George W. Bush, and Ike Turner by or to “manic depression and drug addiction, to years of envy, . . . to a Mississippi childhood that was a trifecta of domestic abuse, sexual treachery and racist violence.” A young James Baldwin enthralled the Harlem faithful. Nina Simone refused the thrall of “warring desires.” It’s the last that clarifies the stakes. Thrall, some time after it meant “slave” to Northern Europeans, found a new Gothic use. Dracula, through hypnosis and sheer erotic power, holds his servants and whole towns in his thrall, the better to protect him while he hides from the sun. Those enthralled submit totally, pleasurably. Influence doesn’t always have to provoke anxiety. There is danger of losing oneself, of being absorbed by the force of another’s will and gaze and magnetism, and that’s before they seize upon your neck. But there’s a reason Dracula persists. Beneath our regimens of self-help, self-care, and self-improvement, we might think briefly of annihilation and find it sweet. Nuclear war has returned to the realm of dinner table conversation, weighing on the minds of the public more than it has in a generation.

Nuclear war has returned to the realm of dinner table conversation, weighing on the minds of the public more than it has in a generation.