Saugat Bolakhe in Quanta:

Memory doesn’t represent a single scientific mystery; it’s many of them. Neuroscientists and psychologists have come to recognize varied types of memory that coexist in our brain: episodic memories of past experiences, semantic memories of facts, short- and long-term memories, and more. These often have different characteristics and even seem to be located in different parts of the brain. But it’s never been clear what feature of a memory determines how or why it should be sorted in this way.

Memory doesn’t represent a single scientific mystery; it’s many of them. Neuroscientists and psychologists have come to recognize varied types of memory that coexist in our brain: episodic memories of past experiences, semantic memories of facts, short- and long-term memories, and more. These often have different characteristics and even seem to be located in different parts of the brain. But it’s never been clear what feature of a memory determines how or why it should be sorted in this way.

Now, a new theory backed by experiments using artificial neural networks proposes that the brain may be sorting memories by evaluating how likely they are to be useful as guides in the future. In particular, it suggests that many memories of predictable things, ranging from facts to useful recurring experiences — like what you regularly eat for breakfast or your walk to work — are saved in the brain’s neocortex, where they can contribute to generalizations about the world. Memories less likely to be useful — like the taste of that unique drink you had at that one party — are kept in the seahorse-shaped memory bank called the hippocampus.

More here.

Even people around President Biden now accept that pulling out of Afghanistan in the way the US did two years ago was an utter disaster. It ruined the lives of millions, destroyed the social and economic advances of 20 years, and returned the country’s women to a state of slavery. The result was to make the US look weak and pathetic; no wonder Vladimir Putin decided he could safely invade Ukraine, only six months later.

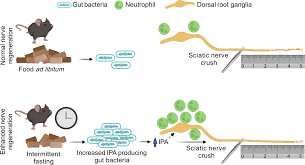

Even people around President Biden now accept that pulling out of Afghanistan in the way the US did two years ago was an utter disaster. It ruined the lives of millions, destroyed the social and economic advances of 20 years, and returned the country’s women to a state of slavery. The result was to make the US look weak and pathetic; no wonder Vladimir Putin decided he could safely invade Ukraine, only six months later. In a recent study published in Nature, Serger et al. connected intermittent fasting (IF) to gut microbiome alterations and enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration following injury.

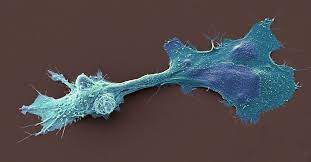

In a recent study published in Nature, Serger et al. connected intermittent fasting (IF) to gut microbiome alterations and enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration following injury. Over the past few years, a flurry of studies have found that tumors harbor a remarkably rich array of bacteria, fungi and viruses. These surprising findings have led many scientists to

Over the past few years, a flurry of studies have found that tumors harbor a remarkably rich array of bacteria, fungi and viruses. These surprising findings have led many scientists to  Italy would be where I would whisk, mix, and knead my way into an idealized self. If I could get there, I would shed my anxious energy and compulsive need for affirmation, my nasty addiction to the cool-mint vape. I would slow down; I would journal. I would become tan and strong from simple pastas. I would eat intuitively — no more take-out burritos in the middle of the night, no more nubby cheeses scrounged from the bowels of the fridge. If I could find a way to go to Italy, I would become a real baker.

Italy would be where I would whisk, mix, and knead my way into an idealized self. If I could get there, I would shed my anxious energy and compulsive need for affirmation, my nasty addiction to the cool-mint vape. I would slow down; I would journal. I would become tan and strong from simple pastas. I would eat intuitively — no more take-out burritos in the middle of the night, no more nubby cheeses scrounged from the bowels of the fridge. If I could find a way to go to Italy, I would become a real baker. One day, while threading a needle to sew a button, I noticed that my tongue was sticking out. The same thing happened later, as I carefully cut out a photograph. Then another day, as I perched precariously on a ladder painting the window frame of my house, there it was again!

One day, while threading a needle to sew a button, I noticed that my tongue was sticking out. The same thing happened later, as I carefully cut out a photograph. Then another day, as I perched precariously on a ladder painting the window frame of my house, there it was again! Smith was not only a great thinker but also a great writer. He was an empirical economist whose sketchy data were

Smith was not only a great thinker but also a great writer. He was an empirical economist whose sketchy data were  Halfway through my interview with the co-founder of

Halfway through my interview with the co-founder of  The Coming Wave distils what is about to happen in a forcefully clear way. AI, Suleyman argues, will rapidly reduce the price of achieving any goal. Its astonishing labour-saving and problem-solving capabilities will be available cheaply and to anyone who wants to use them. He memorably calls this “the plummeting cost of power”. If the printing press allowed ordinary people to own books, and the silicon chip put a computer in every home, AI will democratise simply doing things. So, sure, that means getting a virtual assistant to set up a company for you, or using a swarm of builder bots to throw up an extension. Unfortunately, it also means engineering a run on a bank, or creating a deadly virus using a DNA synthesiser.

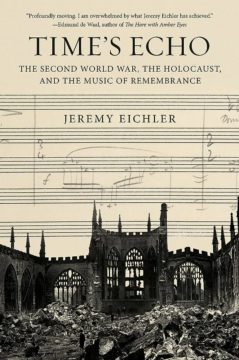

The Coming Wave distils what is about to happen in a forcefully clear way. AI, Suleyman argues, will rapidly reduce the price of achieving any goal. Its astonishing labour-saving and problem-solving capabilities will be available cheaply and to anyone who wants to use them. He memorably calls this “the plummeting cost of power”. If the printing press allowed ordinary people to own books, and the silicon chip put a computer in every home, AI will democratise simply doing things. So, sure, that means getting a virtual assistant to set up a company for you, or using a swarm of builder bots to throw up an extension. Unfortunately, it also means engineering a run on a bank, or creating a deadly virus using a DNA synthesiser. In 1947, the Black German musician Fasia Jansen stood on a street in Hamburg and began to sing the music of Brecht in her thick Low German accent to anyone passing by. Perhaps she’d learned the songs from prisoners and internees at Neuengamme, the concentration camp where she’d been forced to work four years earlier. Perhaps she’d learned them in the early days after the war, when she’d performed with Holocaust survivors at a hospital in 1945. One thing was clear: As Jansen wrestled with her trauma, song was at the center of her experience.

In 1947, the Black German musician Fasia Jansen stood on a street in Hamburg and began to sing the music of Brecht in her thick Low German accent to anyone passing by. Perhaps she’d learned the songs from prisoners and internees at Neuengamme, the concentration camp where she’d been forced to work four years earlier. Perhaps she’d learned them in the early days after the war, when she’d performed with Holocaust survivors at a hospital in 1945. One thing was clear: As Jansen wrestled with her trauma, song was at the center of her experience. Herman Mark Schwartz in The Syllabus:

Herman Mark Schwartz in The Syllabus: