Kate Mackenzie and Tim Sahay in The Polycrisis:

The precursor of 2022’s energy crisis was 2020–2021’s vaccine apartheid. These shortages were in no way natural but reflected financial and geopolitical hierarchies: those with more power and resources bid up prices and developing countries lost out in the process. In the case of vaccines, millions of lives were lost. The energy crisis too is a question of life and death. Expensive gas-powered air conditioners in Europe subsidized with nearly a trillion euros of deficit-financing really did mean lights out for millions of Pakistanis and Bangladeshis.

In both these cases, developing countries were reminded that the existing world order is rigged against them. Global inequality rose sharply. Their shortages of money (especially the right kind of money) and inability to borrow cheaply put them at the back of the queue. The grim fact that the West not only denied poor countries IP for technology to make their own mRNA vaccines in the hour of distress, but hoarded vaccines past their sell-by date, revealed the system’s bankruptcy. Ajay Banga, the new World Bank chief, described the growing mistrust “pulling the Global North and South apart at a time when we need to be uniting.”

On August 24, more than sixty leaders of the largest developing countries met at the BRICS Summit in Johannesburg, chaired by South African President Ramaphosa. High on the meeting’s agenda were multilateralism, reform, and sustainable development. Brazil’s President Lula Inácio da Silva, who founded the BRICS group in 2009, bluntly summarized: “We cannot accept a green neocolonialism that imposes trade barriers and protectionist policies under the pretext of protecting the environment.” By the summit’s end the group had announced six new members: Ethiopia, Egypt, Argentina, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

More here.

Samuel Moyn in Boston Review:

Samuel Moyn in Boston Review:

In 2012, the mathematician Shinichi Mochizuki claimed he had solved the abc conjecture, a major open question in number theory about the relationship between addition and multiplication. There was just one problem: His proof, which was more than 500 pages long, was completely impenetrable. It relied on a snarl of new definitions, notation, and theories that nearly all mathematicians found impossible to make sense of. Years later, when two mathematicians translated large parts of the proof into more familiar terms, they pointed to what one called a “

In 2012, the mathematician Shinichi Mochizuki claimed he had solved the abc conjecture, a major open question in number theory about the relationship between addition and multiplication. There was just one problem: His proof, which was more than 500 pages long, was completely impenetrable. It relied on a snarl of new definitions, notation, and theories that nearly all mathematicians found impossible to make sense of. Years later, when two mathematicians translated large parts of the proof into more familiar terms, they pointed to what one called a “ A recent rise in activism in Iran has added a new chapter to the country’s long-standing history of murals and other public art. But as the

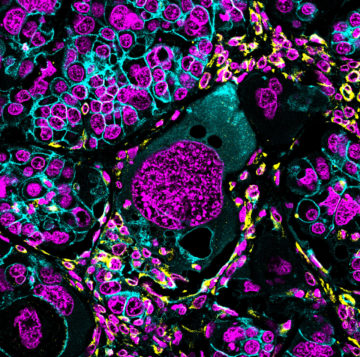

A recent rise in activism in Iran has added a new chapter to the country’s long-standing history of murals and other public art. But as the  In Consciousness as Complex Event: Towards a New Physicalism, Craig DeLancey argues that what makes conscious (or “phenomenal”) experiences mysterious and seemingly impossible to explain is that they are extremely complex brain events. This is then used to debunk the most influential anti-physicalist arguments, such as the knowledge argument. A new “complexity-based” way of thinking about physicalism is then said to emerge.

In Consciousness as Complex Event: Towards a New Physicalism, Craig DeLancey argues that what makes conscious (or “phenomenal”) experiences mysterious and seemingly impossible to explain is that they are extremely complex brain events. This is then used to debunk the most influential anti-physicalist arguments, such as the knowledge argument. A new “complexity-based” way of thinking about physicalism is then said to emerge. The opening sentence of Jacob Mikanowski’s sweeping history of Eastern Europe—“a place,” he asserts, “that doesn’t exist”—calls to mind a seminal 1983 essay by the recently deceased Czech-French novelist, Milan Kundera. In A Kidnapped West: A Tragedy of Central Europe, Kundera reminded his readers that Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia were historically and culturally closer to the West than to the Soviet East, and should therefore be thought of as central rather than eastern European. Alas, his appeal fell on deaf ears, and the region remains “eastern,” shorthand for a place where, rumor has it, nobody smiles and the smell of burned cabbage wafts through the corridors of charmless, concrete apartment blocks. Indeed, western prejudice was never more in evidence than during the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when many commentators painted the war as just another incomprehensible scuffle in the other Europe, among the denizens of lands once obscured by the Iron Curtain.

The opening sentence of Jacob Mikanowski’s sweeping history of Eastern Europe—“a place,” he asserts, “that doesn’t exist”—calls to mind a seminal 1983 essay by the recently deceased Czech-French novelist, Milan Kundera. In A Kidnapped West: A Tragedy of Central Europe, Kundera reminded his readers that Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia were historically and culturally closer to the West than to the Soviet East, and should therefore be thought of as central rather than eastern European. Alas, his appeal fell on deaf ears, and the region remains “eastern,” shorthand for a place where, rumor has it, nobody smiles and the smell of burned cabbage wafts through the corridors of charmless, concrete apartment blocks. Indeed, western prejudice was never more in evidence than during the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, when many commentators painted the war as just another incomprehensible scuffle in the other Europe, among the denizens of lands once obscured by the Iron Curtain. An artificial-intelligence system can describe how compounds smell simply by analysing their molecular structures — and its descriptions are often similar to those of trained human sniffers.

An artificial-intelligence system can describe how compounds smell simply by analysing their molecular structures — and its descriptions are often similar to those of trained human sniffers.

Over the last year, AI large-language models (LLMs) like

Over the last year, AI large-language models (LLMs) like  One hundred and fifty years ago, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”

One hundred and fifty years ago, John Stuart Mill died in his home in Avignon. His last words were to his step-daughter, Helen Taylor: “You know that I have done my work.”