Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

We often think of proteins as immutable 3D sculptures. That’s not quite right. Many proteins are transformers that twist and change their shapes depending on biological needs. One configuration may propagate damaging signals from a stroke or heart attack. Another may block the resulting molecular cascade and limit harm.

We often think of proteins as immutable 3D sculptures. That’s not quite right. Many proteins are transformers that twist and change their shapes depending on biological needs. One configuration may propagate damaging signals from a stroke or heart attack. Another may block the resulting molecular cascade and limit harm.

In a way, proteins act like biological transistors—on-off switches at the root of the body’s molecular “computer” determining how it reacts to external and internal forces and feedback. Scientists have long studied these shape-shifting proteins to decipher how our bodies function. But why rely on nature alone? Can we create biological “transistors,” unknown to the biological universe, from scratch? Enter AI. Multiple deep learning methods can already accurately predict protein structures—a breakthrough half a century in the making. Subsequent studies using increasingly powerful algorithms have hallucinated protein structures untethered by the forces of evolution. Yet these AI-generated structures have a downfall: although highly intricate, most are completely static—essentially, a sort of digital protein sculpture frozen in time.

A new study in Science this month broke the mold by adding flexibility to designer proteins. The new structures aren’t contortionists without limits. However, the designer proteins can stabilize into two different forms—think a hinge in either an open or closed configuration—depending on an external biological “lock.” Each state is analogous to a computer’s “0” or “1,” which subsequently controls the cell’s output. “Before, we could only create proteins that had one stable configuration,” said study author Dr. Florian Praetorius at the University of Washington. “Now, we can finally create proteins that move, which should open up an extraordinary range of applications.” Lead author Dr. David Baker has ideas: “From forming nanostructures that respond to chemicals in the environment to applications in drug delivery, we’re just starting to tap into their potential.”

More here.

It’s fitting that choreographer George Balanchine is experiencing a cultural moment around the 40th anniversary of his death. In the ephemeral realm of dance, the longevity of his influence is unique and it shows no signs of waning. Balanchine’s ballets—beloved for their sophisticated abstraction and musicality—have become staples of the repertoire for ballet companies in the United States and beyond, and they have been performed more often since his death than during his lifetime. Two institutions jointly founded by Balanchine and impresario Lincoln Kirstein—the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and the School of American Ballet (SAB)—continue to cultivate his artistic legacy on the stages and in the classrooms of Lincoln Center. Among his other accomplishments, Balanchine made The Nutcracker a Christmas classic in the United States, and for many ballet enthusiasts it would be as difficult to conceive of ballet without Balanchine as it would be to spend the holidays without the Mouse King and the Sugar Plum Fairy.

It’s fitting that choreographer George Balanchine is experiencing a cultural moment around the 40th anniversary of his death. In the ephemeral realm of dance, the longevity of his influence is unique and it shows no signs of waning. Balanchine’s ballets—beloved for their sophisticated abstraction and musicality—have become staples of the repertoire for ballet companies in the United States and beyond, and they have been performed more often since his death than during his lifetime. Two institutions jointly founded by Balanchine and impresario Lincoln Kirstein—the New York City Ballet (NYCB) and the School of American Ballet (SAB)—continue to cultivate his artistic legacy on the stages and in the classrooms of Lincoln Center. Among his other accomplishments, Balanchine made The Nutcracker a Christmas classic in the United States, and for many ballet enthusiasts it would be as difficult to conceive of ballet without Balanchine as it would be to spend the holidays without the Mouse King and the Sugar Plum Fairy. In March, 1929, when the twenty-four-year-old Chinese American actress

In March, 1929, when the twenty-four-year-old Chinese American actress  Among the many dolls mentioned in Greta Gerwig’s film Barbie there is one associated with time and memory and literally named after Marcel Proust. It didn’t sell well. Perhaps Mattel got the wrong writer. They could have gone for the same Marcel, but as a comedian, a French, philosophical, disguised partner of Dickens. Critics have been finding Proust funny since 1928—he died in 1922. Christopher Prendergast’s

Among the many dolls mentioned in Greta Gerwig’s film Barbie there is one associated with time and memory and literally named after Marcel Proust. It didn’t sell well. Perhaps Mattel got the wrong writer. They could have gone for the same Marcel, but as a comedian, a French, philosophical, disguised partner of Dickens. Critics have been finding Proust funny since 1928—he died in 1922. Christopher Prendergast’s  Science fiction has long entertained the idea of artificial intelligence becoming conscious — think of HAL 9000, the supercomputer-turned-villain in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. With the rapid progress of artificial intelligence (AI), that possibility is becoming less and less fantastical, and has even been acknowledged by leaders in AI. Last year, for instance, Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the chatbot ChatGPT, tweeted that some of the most cutting-edge AI networks

Science fiction has long entertained the idea of artificial intelligence becoming conscious — think of HAL 9000, the supercomputer-turned-villain in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. With the rapid progress of artificial intelligence (AI), that possibility is becoming less and less fantastical, and has even been acknowledged by leaders in AI. Last year, for instance, Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist at OpenAI, the company behind the chatbot ChatGPT, tweeted that some of the most cutting-edge AI networks  About 10 years ago, a very thick book written by a French economist became a surprising bestseller. It was called

About 10 years ago, a very thick book written by a French economist became a surprising bestseller. It was called  As Borat, the first fake news journalist, I interviewed some college students—three young white men in their ballcaps and polo shirts. It only took a few drinks, and soon they were telling me what they really believed. They asked if, in my country, women are slaves. They talked about how, here in the U.S., “the Jews” have “the upper hand.” When I asked, do you have slaves in America?, they replied, “we wish!” “We should have slaves,” one said, “it would be a better country.” Those young men made a choice. They chose to believe some of the oldest and most vile lies that are at the root of all hate. And so it pains me that we have to say it yet again. The idea that people of color are inferior is a lie. The idea that Jews are dangerous and all-powerful is a lie. The idea that women are not equal to men is a lie. The idea that queer people are a threat to our children is a lie.

As Borat, the first fake news journalist, I interviewed some college students—three young white men in their ballcaps and polo shirts. It only took a few drinks, and soon they were telling me what they really believed. They asked if, in my country, women are slaves. They talked about how, here in the U.S., “the Jews” have “the upper hand.” When I asked, do you have slaves in America?, they replied, “we wish!” “We should have slaves,” one said, “it would be a better country.” Those young men made a choice. They chose to believe some of the oldest and most vile lies that are at the root of all hate. And so it pains me that we have to say it yet again. The idea that people of color are inferior is a lie. The idea that Jews are dangerous and all-powerful is a lie. The idea that women are not equal to men is a lie. The idea that queer people are a threat to our children is a lie. Ten years ago, a tech-savvy group of people with type 1

Ten years ago, a tech-savvy group of people with type 1  ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874–1951) was a pivotal figure in the development of 20th-century music. Of the thousands of composers who came before and after him, he stood alone both as the embodiment of the high Romanticism of the 19th and early 20th centuries led by Gustav Mahler, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss, and as a rebel who broke down the gates of traditions that had ruled music composition for three centuries. After he spent his childhood in pre–World War I Vienna in a Jewish ghetto, Nazi antisemitism drove him from Europe, eventually to land in Los Angeles, where he stayed to the end of his life, teaching first at USC and then UCLA.

ARNOLD SCHOENBERG (1874–1951) was a pivotal figure in the development of 20th-century music. Of the thousands of composers who came before and after him, he stood alone both as the embodiment of the high Romanticism of the 19th and early 20th centuries led by Gustav Mahler, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss, and as a rebel who broke down the gates of traditions that had ruled music composition for three centuries. After he spent his childhood in pre–World War I Vienna in a Jewish ghetto, Nazi antisemitism drove him from Europe, eventually to land in Los Angeles, where he stayed to the end of his life, teaching first at USC and then UCLA. The camera zooms in on the person’s arm to reveal the cells, then a cell nucleus. A DNA strand grows on the screen. The camera focuses on a single atom within the strand, dives into a frenetic cloud of rocketing particles, crosses it, and leaves us in oppressive darkness. An initially imperceptible tiny dot grows smoothly, revealing the atomic nucleus. The narrator lectures that the nucleus of an atom is tens of thousands of times smaller than the atom itself, and poetically concludes that we are made from emptiness.

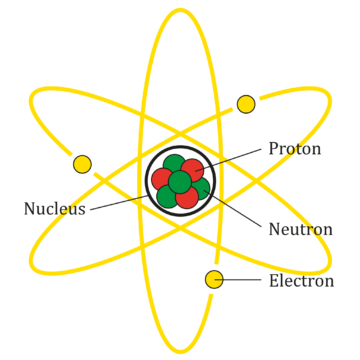

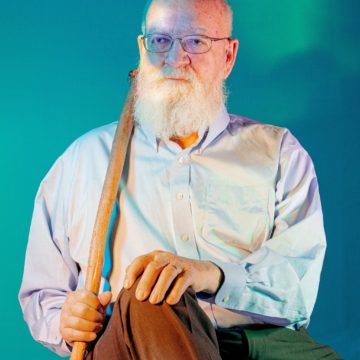

The camera zooms in on the person’s arm to reveal the cells, then a cell nucleus. A DNA strand grows on the screen. The camera focuses on a single atom within the strand, dives into a frenetic cloud of rocketing particles, crosses it, and leaves us in oppressive darkness. An initially imperceptible tiny dot grows smoothly, revealing the atomic nucleus. The narrator lectures that the nucleus of an atom is tens of thousands of times smaller than the atom itself, and poetically concludes that we are made from emptiness. For more than 50 years, Daniel C. Dennett has been right in the thick of some of humankind’s most meaningful arguments: the nature and function of consciousness and religion, the development and dangers of artificial intelligence and the relationship between science and philosophy, to name a few. For Dennett, an éminence grise of American philosophy who is nonetheless perhaps best known as one of the “four horsemen” of modern atheism alongside Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, there are no metaphysical mysteries at the heart of human existence, no magic nor God that makes us who we are. Instead, it’s science and Darwinian evolution all the way down. In his new memoir, “I’ve Been Thinking,” Dennett, a professor emeritus at Tufts University and author of multiple books for popular audiences, traces the development of his worldview, which he is keen to point out is no less full of awe or gratitude than that of those more inclined to the supernatural. “I want people to see what a meaningful, happy life I’ve had with these beliefs,” says Dennett, who is 81. “I don’t need mystery.”

For more than 50 years, Daniel C. Dennett has been right in the thick of some of humankind’s most meaningful arguments: the nature and function of consciousness and religion, the development and dangers of artificial intelligence and the relationship between science and philosophy, to name a few. For Dennett, an éminence grise of American philosophy who is nonetheless perhaps best known as one of the “four horsemen” of modern atheism alongside Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, there are no metaphysical mysteries at the heart of human existence, no magic nor God that makes us who we are. Instead, it’s science and Darwinian evolution all the way down. In his new memoir, “I’ve Been Thinking,” Dennett, a professor emeritus at Tufts University and author of multiple books for popular audiences, traces the development of his worldview, which he is keen to point out is no less full of awe or gratitude than that of those more inclined to the supernatural. “I want people to see what a meaningful, happy life I’ve had with these beliefs,” says Dennett, who is 81. “I don’t need mystery.” If you infect a rabbit with a virus or a bacterium, it’ll start to run a fever. Why? The surprising answer is that fever is not a disease; it’s a defence: a useful evolved mechanism that

If you infect a rabbit with a virus or a bacterium, it’ll start to run a fever. Why? The surprising answer is that fever is not a disease; it’s a defence: a useful evolved mechanism that  I have never told this story in its entirety to anyone: not to my therapist, not to my closest friends, and not even to my family. I’ve divulged bits and pieces of it to different people. When my friends back home in Iran asked me why I was leaving, I made up a thousand different reasons. When my friends in Istanbul asked me what happened and why I came, I said that a part of me had died, that my ambition, courage, and hope for the future had dried up. But I didn’t explain why. I couldn’t connect the single moments into a coherent narrative.

I have never told this story in its entirety to anyone: not to my therapist, not to my closest friends, and not even to my family. I’ve divulged bits and pieces of it to different people. When my friends back home in Iran asked me why I was leaving, I made up a thousand different reasons. When my friends in Istanbul asked me what happened and why I came, I said that a part of me had died, that my ambition, courage, and hope for the future had dried up. But I didn’t explain why. I couldn’t connect the single moments into a coherent narrative. WHEN A DEER, A DOE, STEPPED INTO THE ROAD perhaps a hundred and twenty feet ahead of the car I was driving, it seemed for a moment that she would die, even though, during the same moment, I did not feel afraid that I would hit her. I was calm; I returned my smoking hand to the steering wheel; I braked. The deer seemed to be looking at me. There was a chance she might actually run toward me. I switched off the high-beams. All of this happened in two and a half seconds, before the deer continued across the road, safely to the other side, in a single bound. It was then that, exhaling, I realized the extent to which I had felt for—on behalf of—the animal, and for days after I dwelled on the feeling.

WHEN A DEER, A DOE, STEPPED INTO THE ROAD perhaps a hundred and twenty feet ahead of the car I was driving, it seemed for a moment that she would die, even though, during the same moment, I did not feel afraid that I would hit her. I was calm; I returned my smoking hand to the steering wheel; I braked. The deer seemed to be looking at me. There was a chance she might actually run toward me. I switched off the high-beams. All of this happened in two and a half seconds, before the deer continued across the road, safely to the other side, in a single bound. It was then that, exhaling, I realized the extent to which I had felt for—on behalf of—the animal, and for days after I dwelled on the feeling.