Sarah Churchwell in Literary Review:

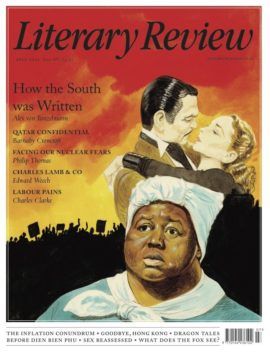

The night before Gone with the Wind’s Atlanta premiere in 1939, there was a ball at a plantation. Dressed as slaves, the children of the black Ebenezer Baptist Church choir performed for an all-white audience. They sang ‘There’s Plenty of Good Room in Heaven’; the actress playing Belle Watling, Rhett Butler’s tart with a heart, wept. The scene is already striking: a painfully literal example of the mythologising of the South for white consumption, redefining slavery as harmless and the slaves themselves as grateful. Yet Sarah Churchwell finds a jaw-dropping detail: ‘One of the little Black children dressed as a slave and bringing a sentimental tear to white America’s eye was a ten-year-old boy named Martin Luther King, Jr, who would be dead in thirty years for daring to dream of racial equality in America.’

The night before Gone with the Wind’s Atlanta premiere in 1939, there was a ball at a plantation. Dressed as slaves, the children of the black Ebenezer Baptist Church choir performed for an all-white audience. They sang ‘There’s Plenty of Good Room in Heaven’; the actress playing Belle Watling, Rhett Butler’s tart with a heart, wept. The scene is already striking: a painfully literal example of the mythologising of the South for white consumption, redefining slavery as harmless and the slaves themselves as grateful. Yet Sarah Churchwell finds a jaw-dropping detail: ‘One of the little Black children dressed as a slave and bringing a sentimental tear to white America’s eye was a ten-year-old boy named Martin Luther King, Jr, who would be dead in thirty years for daring to dream of racial equality in America.’

Churchwell has written about American mythology before, notably in Behold America: A History of America First and the American Dream, as well as in works on Marilyn Monroe and The Great Gatsby. This time it feels like she has hit the motherlode: ‘The heart of the [American] myth, as well as its mind and its nervous system, most of its arguments and beliefs, its loves and hates, its lies and confusions and defence mechanisms and wish fulfilments, are all captured (for the most part inadvertently) in America’s most famous epic romance.’ For Churchwell, ‘Gone with the Wind provides a kind of skeleton key, unlocking America’s illusions about itself.’

More here.