Category: Recommended Reading

The Secret History Of A Psychoanalytic Cult

Hannah Zeavin at Bookforum:

According to The Sullivanians, the story goes something like this. In the ’50s, just as Jim Jones was moving to make a Marxist revolution by nestling politics inside an Indianapolis church, one Saul Newton, alongside his fourth wife, Jane Pearce, sought to braid Marx and Freud and spark a revolution in and through the consulting room. Communist movements, they felt, had failed precisely because they left out the psyche and socialization. Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, was being used in conservative ways and was largely pro-family, pro-babies, and pro-adjustment to the difficulty of same. To unlock their full potential, each theory needed the other. The problem was that Newton was not a clinician. (The solution: lie about it.)

According to The Sullivanians, the story goes something like this. In the ’50s, just as Jim Jones was moving to make a Marxist revolution by nestling politics inside an Indianapolis church, one Saul Newton, alongside his fourth wife, Jane Pearce, sought to braid Marx and Freud and spark a revolution in and through the consulting room. Communist movements, they felt, had failed precisely because they left out the psyche and socialization. Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, was being used in conservative ways and was largely pro-family, pro-babies, and pro-adjustment to the difficulty of same. To unlock their full potential, each theory needed the other. The problem was that Newton was not a clinician. (The solution: lie about it.)

While Pearce was a medical doctor and licensed to practice psychotherapy, Newton was not. He claimed that he had mailed his social-work thesis, but his advisor never received it (dog, homework).

more here.

Simone de Beauvoir On Freedom And Difference

Toril Moi at The Point:

One evening in 1932, Simone de Beauvoir joined Jean-Paul Sartre and his old schoolfriend, the philosopher Raymond Aron, for a drink at a bar in Montparnasse. The three of them enthusiastically ordered apricot cocktails, the specialty of the house. Aron, who had just returned to Paris from a year studying philosophy in Berlin, suddenly pointed to his glass and said: “If you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” According to Beauvoir, Sartre “turned pale with emotion.” This was exactly what he wanted to do: “describe objects just as he saw and touched them, and to make philosophy out of it.”

One evening in 1932, Simone de Beauvoir joined Jean-Paul Sartre and his old schoolfriend, the philosopher Raymond Aron, for a drink at a bar in Montparnasse. The three of them enthusiastically ordered apricot cocktails, the specialty of the house. Aron, who had just returned to Paris from a year studying philosophy in Berlin, suddenly pointed to his glass and said: “If you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” According to Beauvoir, Sartre “turned pale with emotion.” This was exactly what he wanted to do: “describe objects just as he saw and touched them, and to make philosophy out of it.”

Phenomenology—the tradition of philosophy after Husserl and Heidegger—sets aside questions of essence and ontology and tries instead to grasp phenomena as a particular subject experiences them. A philosophy concerned with perception and experience would allow Sartre to shrink the gap between literature and philosophy and write philosophical texts filled with scintillating, though sometimes sexist, descriptions, anecdotes and stories: a cafe waiter playing at being a waiter, a woman who has gone to a cafe for a first date, a man flooded with shame when he is caught peeping through a keyhole in a hotel corridor.

more here.

Toril Moi: The Question Of The New In Literary History

The Best Movies of 2023 (So Far)

From Vulture:

Not to trigger the ol’ existential panic, but 2023 is drawing to a close quite soon. That means it’s time to tally what the year in movies has brought us. So far, we’ve seen Wes Anderson unveil what might be his masterpiece, his maddest expression yet of our human need for control. We’ve learned that the romantic comedy isn’t dead; it’s streaming on Hulu. Martin Scorsese did it again. It’s been a fantastic year for animation, too, with stunners like Suzume, the anime auteur Makoto Shinkai’s swoon-worthy latest, Hayao Miyazaki’s return, and Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. (You ever weep at the sheer scope of a movie’s visual imagination before? You will!) Musicians Teyana Taylor and Park Ji-min have both proved themselves born movie stars. We even got a great Marvel movie — that increasing rarity — in James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy swan song. We had Barbenheimer! Here are our favorite films of the year so far, curated by Vulture film critics Alison Willmore, Bilge Ebiri, and Angelica Jade Bastién.

Not to trigger the ol’ existential panic, but 2023 is drawing to a close quite soon. That means it’s time to tally what the year in movies has brought us. So far, we’ve seen Wes Anderson unveil what might be his masterpiece, his maddest expression yet of our human need for control. We’ve learned that the romantic comedy isn’t dead; it’s streaming on Hulu. Martin Scorsese did it again. It’s been a fantastic year for animation, too, with stunners like Suzume, the anime auteur Makoto Shinkai’s swoon-worthy latest, Hayao Miyazaki’s return, and Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. (You ever weep at the sheer scope of a movie’s visual imagination before? You will!) Musicians Teyana Taylor and Park Ji-min have both proved themselves born movie stars. We even got a great Marvel movie — that increasing rarity — in James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy swan song. We had Barbenheimer! Here are our favorite films of the year so far, curated by Vulture film critics Alison Willmore, Bilge Ebiri, and Angelica Jade Bastién.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Casida of the Rose

… The rose

was not searching for the sunrise:

almost eternal on its branch,

it was searching for something else.

… The rose

was not searching for darkness or science:

borderline of flesh and dream,

it was searching for something else.

… The rose

was not searching for the rose.

Motionless in the sky

it was searching for something else.

by Frederico García Lorca

translation by Robert Bly

from News of the Universe

Sierra Club Books, 1995

Cancer Metastasizes Via Fusion of Tumor and Immune Cells

Marcus Banks in The Scientist:

Cancer metastasizes through the fusion of tumor cells with immune cells, according to a case report published online May 28 in Cancer Genetics. “We think what is happening is the initial cancer cells from the primary tumor are blending or hybridizing with immune system cells that respond to the tumor as nonself. By hybridizing with those immune system cells, it looks like ‘self’ so that the immune system doesn’t attack and destroy [the tumor],” says first author Greggory LaBerge, a medical geneticist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine who also directs the Denver Police Department’s Forensics and Evidence Division. LaBerge and his colleagues analyzed the DNA of a woman in her late 70s who had received a bone marrow transplant from an anonymous male donor several years earlier as treatment for her chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. She later developed metastatic melanoma.

Cancer metastasizes through the fusion of tumor cells with immune cells, according to a case report published online May 28 in Cancer Genetics. “We think what is happening is the initial cancer cells from the primary tumor are blending or hybridizing with immune system cells that respond to the tumor as nonself. By hybridizing with those immune system cells, it looks like ‘self’ so that the immune system doesn’t attack and destroy [the tumor],” says first author Greggory LaBerge, a medical geneticist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine who also directs the Denver Police Department’s Forensics and Evidence Division. LaBerge and his colleagues analyzed the DNA of a woman in her late 70s who had received a bone marrow transplant from an anonymous male donor several years earlier as treatment for her chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. She later developed metastatic melanoma.

…The authors used this sample to test a theory that immune cells and cancer cells fuse to lead to metastasis. Because the immune cells had the genome of the donor, while the cancer cells had the genome of the patient, it was possible to track the relative proportion of each at every stage in the metastatic journey. The team’s hypothesis was that, if patient and donor cells were fused together at every point in metastasis, this would support the idea that the patient’s metastasis occurred due to such fusion. If only the patient’s DNA were evident at later steps of metastasis, then this would disprove the hypothesis that fusion fuels metastasis.

More here.

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

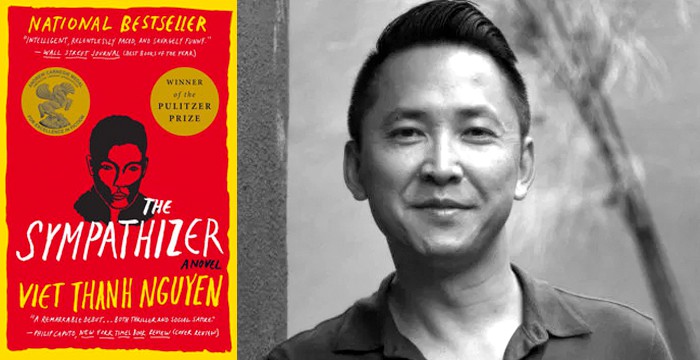

Memory, Identity, Representation: A Conversation with Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author of “The Sympathizer”

From APA Studies on Asian and Asian American Philosophers and Philosophies:

The modern age, Edward W. Said poignantly observes, is largely the age of the refugee, an era of displaced people from mass immigration. Writing about what it means to be a refugee, he admits, is, however, deceptively hard. Because the anguish of existing in a permanent state of homelessness is a predicament that most people rarely experience frsthand, there is often a tendency to objectify the pain, to make the experience “aesthetically and humanistically comprehensible,” to “banalize its mutilations,” and to understand it as “good for us.” Rare is the literature that can meaningfully and empathetically capture the scale, depth, and magnitude of the suffering of those who are today displaced and rendered homeless by modern warfare, colonialism, and “the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarian rulers.”2 It is not surprising therefore, as Said suggests, that the most enduring stories about being an exile come from those who have personally been exiled themselves, ones like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Eqbal Ahmad, Joseph Conrad, and Mahmoud Darwish, who have embodied the experiences of living without a home, without a fxed identity, and without a country. Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American writer and academic Viet Thanh Nguyen, a refugee himself, is one such rare voice in American literature today, a voice that has been a relentless force in making visible, through storytelling, the highly diverse and multifaceted experiences of Vietnamese refugees arriving, settling, and living in diferent parts of the United States since the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

The modern age, Edward W. Said poignantly observes, is largely the age of the refugee, an era of displaced people from mass immigration. Writing about what it means to be a refugee, he admits, is, however, deceptively hard. Because the anguish of existing in a permanent state of homelessness is a predicament that most people rarely experience frsthand, there is often a tendency to objectify the pain, to make the experience “aesthetically and humanistically comprehensible,” to “banalize its mutilations,” and to understand it as “good for us.” Rare is the literature that can meaningfully and empathetically capture the scale, depth, and magnitude of the suffering of those who are today displaced and rendered homeless by modern warfare, colonialism, and “the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarian rulers.”2 It is not surprising therefore, as Said suggests, that the most enduring stories about being an exile come from those who have personally been exiled themselves, ones like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Eqbal Ahmad, Joseph Conrad, and Mahmoud Darwish, who have embodied the experiences of living without a home, without a fxed identity, and without a country. Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American writer and academic Viet Thanh Nguyen, a refugee himself, is one such rare voice in American literature today, a voice that has been a relentless force in making visible, through storytelling, the highly diverse and multifaceted experiences of Vietnamese refugees arriving, settling, and living in diferent parts of the United States since the Fall of Saigon in 1975.

More here. [Scroll down to page 26.]

Cryptographers are preparing for new quantum computers that will break their ciphers

Neil Savage in Nature:

In July 2022, a pair of mathematicians in Belgium startled the cybersecurity world. They took a data-encryption scheme that had been designed to withstand attacks from quantum computers so sophisticated they don’t yet exist, and broke it in 10 minutes using a nine-year-old, non-quantum PC.

In July 2022, a pair of mathematicians in Belgium startled the cybersecurity world. They took a data-encryption scheme that had been designed to withstand attacks from quantum computers so sophisticated they don’t yet exist, and broke it in 10 minutes using a nine-year-old, non-quantum PC.

“I think I was more surprised than most,” says Thomas Decru, a mathematical cryptographer, who worked on the attack while carrying out postdoctoral research at the Catholic University of Leuven (KU Leuven) in Belgium. He and his PhD supervisor Wouter Castryck had sketched out the mathematics of the approach on a whiteboard, but Decru hadn’t been sure it would work — until the pair actually ran it on a PC. “It took a while for me to let it sink in: ‘Okay, it’s broken.’”

More here.

Interview of Michael Spence, Nobel laureate in economics

From Project Syndicate:

Project Syndicate: You, Anu Madgavkar, and Sven Smit recently pointed out that “economic dynamism and improvements in living standards are vital both to finance climate action and to ensure adequate public support for it.” In your new book, Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World – co-authored with Gordon Brown and Mohamed A. El-Erian (with Reid Lidow) – you highlight major growth headwinds, including “trends that have reduced the supply elasticity of the global system.” In what ways should this new supply environment change how we think about economic growth and stability?

Project Syndicate: You, Anu Madgavkar, and Sven Smit recently pointed out that “economic dynamism and improvements in living standards are vital both to finance climate action and to ensure adequate public support for it.” In your new book, Permacrisis: A Plan to Fix a Fractured World – co-authored with Gordon Brown and Mohamed A. El-Erian (with Reid Lidow) – you highlight major growth headwinds, including “trends that have reduced the supply elasticity of the global system.” In what ways should this new supply environment change how we think about economic growth and stability?

Michael Spence: The last two decades brought a massive increase in productive capacity, as rapidly growing emerging economies, especially China, were integrated into the global economy. As a result, the supply side was not a significant constraint on growth. In fact, global growth remained largely robust even as productivity declined, though there were, of course, some setbacks, such as during the 2008 global financial crisis.

This has changed.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

The Wretched of the Earth

I don’t like to start my day off with the dreadful news.

I feel fresh and enlivened in the mornings and refuse to taint

this short-lived joy with the hideous happenings “out there.”

Instead, I turn to the artists, poets, and philosophers

—the true awakeners of the human spirit.

Black coffee, old books, and the music of Gustav Mahler

— the breakfast of champs.

Today, as the world continues to trudge along on its ruinous path,

I’m reading the essays of one of the most eloquent and profound

writers of the 20th century, James Baldwin.

He once reminded us:

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented

in the history of the world, but then you read. It was

books that taught me that the things that tormented me most

were the very things that connected me with all the people

who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

The New York Times once labeled Baldwin “the best essayist in this country

—a man whose power has always been in his reasoned, biting sarcasm;

his insistence on removing layer by layer the hardened skin with which

Americans shield themselves from their country.”

by Writer Unknown

from Poetic Outlaws

The inside story of ChatGPT’s astonishing potential

A Life of Anthony Hecht

Robert Archambeau at The Hudson Review:

He constructed something else to go along with his literary life, too: he created a persona, what we might almost call a carapace. In an academic career that took him on what he called “many years of pilgrimage over the academic map,” from Smith to Bard to Rochester to Georgetown, he adopted the dress and mannerisms of an English gentleman, perhaps in response to what he called the “covert anti-semitism” in some of the departments in which he taught. Beginning his career at a time when creative writers were still viewed with some suspicion by their more conventionally trained colleagues, Hecht compensated by becoming what Yezzi calls “the very model of a modern literature professor: bearded, tweedy, pensive, reserved.” Hecht gravitated to teaching Shakespeare more than creative writing. While his love of Shakespeare was deep-seated, it was also an important part of this process of self-creation. “Nothing could be more canonical” than Shakespeare, Yezzi writes, nothing “more revered and accepted on both intellectual and aesthetic grounds.”

He constructed something else to go along with his literary life, too: he created a persona, what we might almost call a carapace. In an academic career that took him on what he called “many years of pilgrimage over the academic map,” from Smith to Bard to Rochester to Georgetown, he adopted the dress and mannerisms of an English gentleman, perhaps in response to what he called the “covert anti-semitism” in some of the departments in which he taught. Beginning his career at a time when creative writers were still viewed with some suspicion by their more conventionally trained colleagues, Hecht compensated by becoming what Yezzi calls “the very model of a modern literature professor: bearded, tweedy, pensive, reserved.” Hecht gravitated to teaching Shakespeare more than creative writing. While his love of Shakespeare was deep-seated, it was also an important part of this process of self-creation. “Nothing could be more canonical” than Shakespeare, Yezzi writes, nothing “more revered and accepted on both intellectual and aesthetic grounds.”

more here.

Anthony Hecht’s Italian Journey

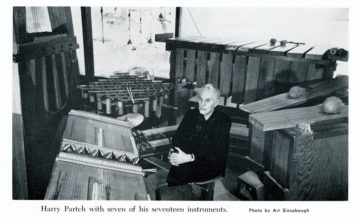

Listening Anew To An American Nomad

David A. Taylor at The American Scholar:

In winter 1940, beside a highway in the California desert, a reedy man bends down for a closer look at the road’s guardrail, where someone has scribbled graffiti: It’s January twenty-six. I’m freezing. Going home. I’m hungry and broke. I wish I was dead. But today I am a man … The onlooker feels a pang of recognition. He can hear these words in his head—the beginnings of another song.

In winter 1940, beside a highway in the California desert, a reedy man bends down for a closer look at the road’s guardrail, where someone has scribbled graffiti: It’s January twenty-six. I’m freezing. Going home. I’m hungry and broke. I wish I was dead. But today I am a man … The onlooker feels a pang of recognition. He can hear these words in his head—the beginnings of another song.

That onlooker was Harry Partch, a musician and writer who balked at the strictures of Western music to become one of the most influential avant-garde composers of the 20th century. Few people today have ever heard of him—Partch seemed to position himself very far from folk hero, and he rarely gets mentioned in the same breath as his contemporaries Woody Guthrie or Huddy Ledbetter, better known as Leadbelly, who drew on deep folk traditions for their music. By contrast, Partch has long had the reputation of an iconoclast and a wanderer. His compositions are written for instruments he built and in complex scales of his own devising, thrumming like wild, futurist gamelan performances.

more here.

Biophysicists Uncover Powerful Symmetries in Living Tissue

Elise Cutts in Quanta Magazine:

Luca Giomi still remembers the time when, as a young graduate student, he watched two videos of droplets streaming from an inkjet printer. The videos were practically identical — except one wasn’t a video at all. It was a simulation. “I was absolutely mind-blown,” said Giomi, a biophysicist at Leiden University. “You could predict everything about the ink droplets.”

Luca Giomi still remembers the time when, as a young graduate student, he watched two videos of droplets streaming from an inkjet printer. The videos were practically identical — except one wasn’t a video at all. It was a simulation. “I was absolutely mind-blown,” said Giomi, a biophysicist at Leiden University. “You could predict everything about the ink droplets.”

The simulation was powered by the mathematical laws of fluid dynamics, which describes how gases and liquids behave. And now, years after admiring those ink droplets, Giomi still wonders how he might achieve that level of precision for systems that are a bit more complicated than ink droplets. “My dream is really to use this much predictive power in the service of biophysics,” he said.

Giomi and his colleagues just took an important step toward that goal. In a study published in Nature Physics, they conclude that sheets of epithelial tissue, which make up skin and sheathe internal organs, act like liquid crystals — materials that are ordered like solids but flow like liquids. To make that connection, the team demonstrated that two distinct symmetries coexist in epithelial tissue. These different symmetries, which determine how liquid crystals respond to physical forces, simply appear at different scales.

More here.

Patients don’t know how to navigate the US health system — and it’s costing them

Dylan Scott in Vox:

Of all the culprits that make it harder for Americans to afford and access health care, the sheer confusion many patients experience when trying to select an insurance plan or when faced with an expensive medical bill may be the most overlooked. That’s according to a recent survey from research firm Perry Undem, which reveals the deep confusion Americans feel when receiving health care — confusion that could put them on the hook for higher costs.

Of all the culprits that make it harder for Americans to afford and access health care, the sheer confusion many patients experience when trying to select an insurance plan or when faced with an expensive medical bill may be the most overlooked. That’s according to a recent survey from research firm Perry Undem, which reveals the deep confusion Americans feel when receiving health care — confusion that could put them on the hook for higher costs.

US health care costs are dire enough as-is, and it’s easy to look at the data on US prices for common procedures compared to the prices in other countries, or to compare the out-of-pocket costs Americans typically must pay for medical services under their insurance plan compared to their peers elsewhere and see the issue. It’s the prices, stupid, as some of the country’s leading health care economists once described the problem. And the prices are indeed a big part of the US health system’s shortcomings: Research has shown that people will skip necessary care if they have even a small cost to pay, and recent surveys find one in three Americans say they have postponed medical treatment in the last year due to the cost.

More here.

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

The Fog of Art

Nina Power in Compact:

For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of beauty, the passé concerns of previous centuries, the art world has become the moral directorate of the social order. Malevich’s 1915 “Black Square” became 2020’s Instagram BLM square—and woe betide anyone who failed to correctly perform the ritual. As Guy Debord put it in his 1988 “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” “since art is dead, it has evidently become extremely easy to disguise police as artists.”

For someone working in the culture industries, the only thing worse than having the wrong position on a political controversy is having no position at all. Today’s artists are the high priests of the secular middle classes, with cathedrals (art galleries) in every major city. In recent years, rather than defend free expression and the exploration of beauty, the passé concerns of previous centuries, the art world has become the moral directorate of the social order. Malevich’s 1915 “Black Square” became 2020’s Instagram BLM square—and woe betide anyone who failed to correctly perform the ritual. As Guy Debord put it in his 1988 “Comments on the Society of the Spectacle,” “since art is dead, it has evidently become extremely easy to disguise police as artists.”

The growing tendency of artists to pronounce on everything from microaggressions to macropolitics shows that we need a fundamentally different understanding of the role played by artists and their institutions.

More here.

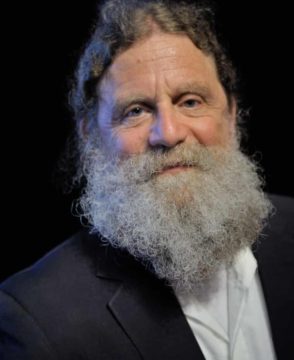

Review of “Determined: Life Without Free Will” by Robert Sapolsky

Oliver Burkeman in The Guardian:

Into this bewildering terrain [the philosophical issue of free will] steps the celebrated behavioural scientist Robert Sapolsky, who sets out in Determined to banish free will once and for all – and to show that confronting its nonexistence needn’t condemn us to amorality or despair. It’s only one aspect of the book’s strangeness that he does this in a style that often calls to mind a hugely knowledgable yet stoned west coast slacker. (I’m still recovering from his reaction, in a book crammed with footnotes and diagrams of motor neurons, to the conclusion that we don’t control our lives: “Fuck. That really blows.”)

His strategy is an ambitious one: to track every link of the causal chain that culminates in human behaviour, starting with what’s happening in the brain in the final few milliseconds before we act, all the way back to how our brains are shaped by early experiences, and even before that, all mostly at the fine-grained level of neurotransmitters and genes.

More here.