Kamala Thiagarajan in Undark:

According to the Million Death Study, one of the largest ongoing global studies of premature mortality, around 58,000 Indians die from snakebites every year, the highest rate in the world. And a growing proportion of these bites come from less common species of venomous snakes in specific pockets of the country, for which, according to researchers at the Indian Institute of Science, available antivenin — also often called antivenom — are not very effective.

According to the Million Death Study, one of the largest ongoing global studies of premature mortality, around 58,000 Indians die from snakebites every year, the highest rate in the world. And a growing proportion of these bites come from less common species of venomous snakes in specific pockets of the country, for which, according to researchers at the Indian Institute of Science, available antivenin — also often called antivenom — are not very effective.

People living in India’s rural areas, who are exposed to a broad range of snakes, are particularly at risk. Treating these patients can be difficult, said Gnaneswar Ch, project leader of the Snake Conservation & Snakebite Mitigation Project at the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust Center for Herpetology, where the Irula Co-op is located.

For instance, in Tamil Nadu, data on snakebites and how to prevent them — gathered by Gnaneswar’s team since 2015 — suggest that people are most likely to be bitten on their legs when they walk across agricultural fields barefoot. And they may not seek treatment at the hospital until hours after the bite, turning first to natural or folk remedies. As a result, Gnaneswar said, “we’re seeing many amputations and loss of limbs.”

More here.

The latest waves of uprisings in Iran following the movement in defence of Iranian women’s freedoms are among the most significant since the Islamic Republic was established after the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1979. The regime’s resulting crackdown has led to mass arrests and prison sentences, as well as a string of executions. These uprisings are symptomatic of prolonged and multifaceted discontent with the Islamic Republic’s perceived governance. One of the oft-cited causes is growing dissatisfaction with principles of government grounded in a religious worldview, and its subsequent patterns of civil liberty violations. The most visible of these violations, which has served as a focal point for resistance, is the law of mandatory hijab for women.

The latest waves of uprisings in Iran following the movement in defence of Iranian women’s freedoms are among the most significant since the Islamic Republic was established after the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in 1979. The regime’s resulting crackdown has led to mass arrests and prison sentences, as well as a string of executions. These uprisings are symptomatic of prolonged and multifaceted discontent with the Islamic Republic’s perceived governance. One of the oft-cited causes is growing dissatisfaction with principles of government grounded in a religious worldview, and its subsequent patterns of civil liberty violations. The most visible of these violations, which has served as a focal point for resistance, is the law of mandatory hijab for women. Monima Chadha has given the world of Anglophone philosophy more reason to take Indian Buddhist philosophy seriously in this closely argued study of the philosophy of the 4th century philosopher Vasubandhu, generally regarded as one of the founders (with his older brother Asaṅga) of the Yogācāra tradition, a tradition associated sometimes with idealism, and sometimes with phenomenology. However one reads the vast literature of this school—or, more specifically, the work of Vasubandhu himself—the close attention that Vasubandhu and his followers give to the philosophy of mind and the structure of subjectivity is inescapable and fascinating. Vasubandhu’s influence on subsequent Buddhist philosophy in India, Tibet, China, and beyond is incalculable, and he is surely one of the two or three most important philosophers in the Indian Buddhist tradition. An investigation of his work by an astute philosopher at home in contemporary philosophy of mind is hence most welcome.

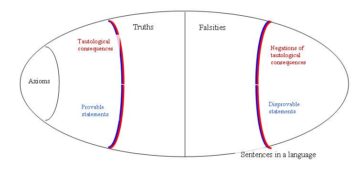

Monima Chadha has given the world of Anglophone philosophy more reason to take Indian Buddhist philosophy seriously in this closely argued study of the philosophy of the 4th century philosopher Vasubandhu, generally regarded as one of the founders (with his older brother Asaṅga) of the Yogācāra tradition, a tradition associated sometimes with idealism, and sometimes with phenomenology. However one reads the vast literature of this school—or, more specifically, the work of Vasubandhu himself—the close attention that Vasubandhu and his followers give to the philosophy of mind and the structure of subjectivity is inescapable and fascinating. Vasubandhu’s influence on subsequent Buddhist philosophy in India, Tibet, China, and beyond is incalculable, and he is surely one of the two or three most important philosophers in the Indian Buddhist tradition. An investigation of his work by an astute philosopher at home in contemporary philosophy of mind is hence most welcome. Since logic is the ultimate go-to discipline for determining whether deductions are valid, one might expect basic logical principles to be indubitable or self-evident – so philosophers

Since logic is the ultimate go-to discipline for determining whether deductions are valid, one might expect basic logical principles to be indubitable or self-evident – so philosophers  WASHINGTON, D.C.—A group of scientists, physicians, ethicists, and advocates sent a

WASHINGTON, D.C.—A group of scientists, physicians, ethicists, and advocates sent a  In 2019, immunologist Jonah Sacha received a shipment of monkeys for his research into infectious diseases. But while conducting preliminary chest X-rays, Sacha found one monkey that stood out for all the wrong reasons: it was carrying the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). The infected animal rendered the entire shipment of 20 monkeys unusable for research because of the risk that the infection would spread. “We lost all of those animals,” says Sacha, who investigates stem-cell transplants as a treatment for HIV at the Oregon Health & Science University’s Oregon National Primate Research Center in Beaverton. “That cost hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage and delayed our research by many years.”

In 2019, immunologist Jonah Sacha received a shipment of monkeys for his research into infectious diseases. But while conducting preliminary chest X-rays, Sacha found one monkey that stood out for all the wrong reasons: it was carrying the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). The infected animal rendered the entire shipment of 20 monkeys unusable for research because of the risk that the infection would spread. “We lost all of those animals,” says Sacha, who investigates stem-cell transplants as a treatment for HIV at the Oregon Health & Science University’s Oregon National Primate Research Center in Beaverton. “That cost hundreds of thousands of dollars of damage and delayed our research by many years.” If letter writing is an art form, then

If letter writing is an art form, then  AI can predict the weather 10 days ahead more accurately than current state-of-the-art simulations, says AI firm Google DeepMind – but meteorologists have warned against abandoning weather models based in real physical principles and just relying on patterns in data, while pointing out shortcomings in the AI approach.

AI can predict the weather 10 days ahead more accurately than current state-of-the-art simulations, says AI firm Google DeepMind – but meteorologists have warned against abandoning weather models based in real physical principles and just relying on patterns in data, while pointing out shortcomings in the AI approach. Francis Bacon is known, above all, for conceiving of a great and terrible human project: the

Francis Bacon is known, above all, for conceiving of a great and terrible human project: the  After serving in the Vietnam War, Charles Figley became interested in the concept of trauma—not only the lasting

After serving in the Vietnam War, Charles Figley became interested in the concept of trauma—not only the lasting  On November 10, 2023, my dear friend John Tooby died—or as he would have put it, finally lost his struggle with entropy. John was a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who together with his wife, Leda Cosmides, founded the field of evolutionary psychology. But that academic accomplishment doesn’t do him justice; it’s the institutional embodiment of the way his mind worked. John had insight into human nature worthy of our greatest novelists and playwrights, grounded in an understanding of the natural world worthy of our greatest scientists. Evolution for him was a link in an explanatory chain that connected human thought and feeling to the laws of the natural world.

On November 10, 2023, my dear friend John Tooby died—or as he would have put it, finally lost his struggle with entropy. John was a Distinguished Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who together with his wife, Leda Cosmides, founded the field of evolutionary psychology. But that academic accomplishment doesn’t do him justice; it’s the institutional embodiment of the way his mind worked. John had insight into human nature worthy of our greatest novelists and playwrights, grounded in an understanding of the natural world worthy of our greatest scientists. Evolution for him was a link in an explanatory chain that connected human thought and feeling to the laws of the natural world. Ever since his seminal first recordings as a leader with his Hot Five and Seven ensembles in the 1920s, jazz musicians have called Louis Armstrong “

Ever since his seminal first recordings as a leader with his Hot Five and Seven ensembles in the 1920s, jazz musicians have called Louis Armstrong “ Take intensifiers like ‘totally’, ‘pretty’ and ‘completely’. We might consciously believe them to be exaggerations undermining the speaker’s point, yet people consistently report seeing linguistic booster-users as more authoritative and likeable than others.

Take intensifiers like ‘totally’, ‘pretty’ and ‘completely’. We might consciously believe them to be exaggerations undermining the speaker’s point, yet people consistently report seeing linguistic booster-users as more authoritative and likeable than others. Consider a few of the bolder claims made by experts. Two years ago, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, vice president of Google Research, had already declared the end of the animal kingdom’s monopoly on language on the strength of Google’s experiments with large language models. LLMs, he argued, “illustrate for the first time the way that language understanding and intelligence can be dissociated from all the embodied and emotional characteristics we share with each other and with many other animals.” In a similar vein, the Stanford University computer scientist Christopher Manning has argued that if “meaning” constitutes “understanding of the network of connections between linguistic form and other things,” be they “objects in the world or other linguistic forms,” then “there can be no doubt” that LLMs can “learn meanings.” Again, the point is that humans have company. The philosopher Tobias Rees (among many others) has gone further, arguing that LLMs constitute a “far-reaching, epoch-making philosophical event” on par with the shift from the premodern conception of language as a divine gift to the modern notion of language as a distinctly human trait, even our defining one. On Rees’s telling, engineers at OpenAI, Google, and Facebook have become the new Descartes and Locke, “[rendering] untenable the idea that only humans have language” and thereby undermining the modern paradigm those philosophers inaugurated. LLMs, for Rees at least, signal modernity’s end.

Consider a few of the bolder claims made by experts. Two years ago, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, vice president of Google Research, had already declared the end of the animal kingdom’s monopoly on language on the strength of Google’s experiments with large language models. LLMs, he argued, “illustrate for the first time the way that language understanding and intelligence can be dissociated from all the embodied and emotional characteristics we share with each other and with many other animals.” In a similar vein, the Stanford University computer scientist Christopher Manning has argued that if “meaning” constitutes “understanding of the network of connections between linguistic form and other things,” be they “objects in the world or other linguistic forms,” then “there can be no doubt” that LLMs can “learn meanings.” Again, the point is that humans have company. The philosopher Tobias Rees (among many others) has gone further, arguing that LLMs constitute a “far-reaching, epoch-making philosophical event” on par with the shift from the premodern conception of language as a divine gift to the modern notion of language as a distinctly human trait, even our defining one. On Rees’s telling, engineers at OpenAI, Google, and Facebook have become the new Descartes and Locke, “[rendering] untenable the idea that only humans have language” and thereby undermining the modern paradigm those philosophers inaugurated. LLMs, for Rees at least, signal modernity’s end.