Category: Recommended Reading

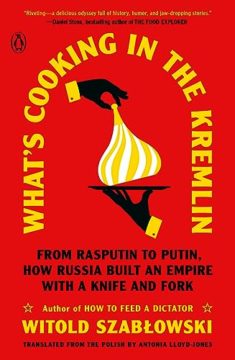

What’s Cooking In The Kremlin?

Jennifer Szalai at the New York Times:

Witold Szablowski describes a number of surprising dishes in his entertaining yet unnerving new book, “What’s Cooking in the Kremlin,” which explores the last century of Russian history through its food. But none is as surreal as the recipe for one of Lenin’s favorites. The instructions for making his “scrambled eggs using three eggs” orders you to break the eggs but not to beat them. What Lenin called “scrambled eggs” were actually fried eggs, with their yolks and whites intact — not scrambled at all.

Witold Szablowski describes a number of surprising dishes in his entertaining yet unnerving new book, “What’s Cooking in the Kremlin,” which explores the last century of Russian history through its food. But none is as surreal as the recipe for one of Lenin’s favorites. The instructions for making his “scrambled eggs using three eggs” orders you to break the eggs but not to beat them. What Lenin called “scrambled eggs” were actually fried eggs, with their yolks and whites intact — not scrambled at all.

Szablowski’s previous books include “How to Feed a Dictator” and “Dancing Bears”; as a Polish journalist born in 1980, he doesn’t have much nostalgia for the Soviet Union, though he has spent considerable time talking to people who do. The chapter about Lenin is mostly narrated by a Moscow tour guide who speaks wistfully of what might have happened if Lenin’s “dreams had come true.”

more here.

Saturday Poem

Enigmas

You asked me what the lobster is weaving there with his

…. golden feet?

I reply, the ocean knows this.

You say, what is the ascidia waiting for in its transparent bell?

…. What is it waiting for?

I tell you it is waiting for time, like you.

You ask me whom the Macrocystis hugs in its arms?

Study, study it, at a certain hour, in a certain sea I know.

You question me about the wicked tusk of the narwhal, and I

…. reply by describing

how the sea unicorn with the harpoon in it dies.

You inquire about the kingfisher’s feathers,

which tremble in the pure springs of the southern tide?

Or you’ve found in the cards a new question touching on the

…. crystal architecture

of the sea anemone, and you’ll deal that to me now?

You want to understand the electric Nature of the ocean spines?

…. The armored stalactite that breaks as it walks?

…. The hook of the angler fish, the music stretched out in the

…. deep places like a thread in the water?

I want to tell you the ocean knows this, that life in its

…. jewel boxes

is endless as the sand, impossible to count, pure,

and among the blood-colored grapes time has made the petal

hard and shiny, made the jellyfish full of light

and untied its knot, letting its musical threads fall

from a horn of plenty made of infinite mother-of-pearl.

The Golden Age of AI Complementarity?

Pia Malaney over at INET:

In markets hungry for the next big breakthrough the latest generation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies has emerged as a potentially revolutionary force, offering a wide array of transformative benefits to humanity. With capabilities in processing data, making predictions, and automating tasks that would once have seemed like science fiction, AI is already altering the ways we live, work, and interact.

What does it mean for a doctor in an underserved area with limited resources to have access to AI systems that facilitate diagnoses based on symptoms and streamline care recommendations? For surgeons to have AI analyze a brain tumor in real-time so that they can decide how much to remove? Big data is already playing a significant role in drug discovery and development; researchers in many areas of academia, including economics, find analysis simplified and expedited.

There is increasing evidence that we are already seeing transformative changes in industries ranging from healthcare to finance. As AI can personalize cancer treatments, identify and diagnose tumors mid-surgery, and rapidly increase the discovery of new molecules that form the basis of drug discovery, its lifesaving impacts are already being felt. In financial markets, it is being used to drive data analytics, data retrieval, predictions, and forecasting. Innovation, often spearheaded by AI and machine learning, has given rise to new products, services, and business models. In education, the possibility of tailoring a curriculum to the needs and pace of each individual student could perhaps transform learning.

Even areas most associated with human creativity are tapping into the productivity benefits of AI.

More here.

The Habitation Economy

Fred Block in Dissent:

In 1980, Margaret Thatcher made her fateful statement that “there is no alternative” to the free market economics that she claimed would revitalize the UK economy. While her policies did not produce the promised results, it remains true that in most places, advocates of more egalitarian and inclusive public policies have been unable to win national office for more than a single consecutive election cycle. Despite frequent claims of its imminent demise, neoliberalism still exerts considerable power in the global economy.

Why is it that efforts to generate broad, durable majority support for egalitarian economic policies have so far failed? Part of the explanation is that advocates of alternative economic policies have continued to operate within the confines of existing economic theories. For the most part, the core analytic framework for economists on the left has not really changed since the 1930s and ’40s.

This is a problem because the economy has changed radically. We need a new paradigm to make sense of our current economy—and to offer a persuasive policy agenda that gives those at the local level the resources and mechanisms they need to shape what they consume and produce.

More here.

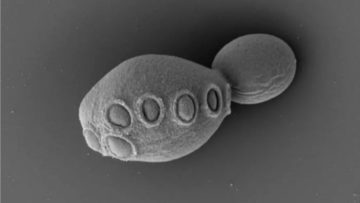

Biologists Unveil the First Living Yeast Cells With Over 50% Synthetic DNA

Edd Gent in Singularity Hub:

Our ability to manipulate the genes of living organisms has expanded dramatically in recent years. Now, researchers are a step closer to building genomes from scratch after unveiling a strain of yeast with more than 50 percent synthetic DNA.

Our ability to manipulate the genes of living organisms has expanded dramatically in recent years. Now, researchers are a step closer to building genomes from scratch after unveiling a strain of yeast with more than 50 percent synthetic DNA.

Since 2006, an international consortium of researchers called the Synthetic Yeast Genome Project has been attempting to rewrite the entire genome of brewer’s yeast. The organism is an attractive target because it’s a eukaryote like us, and it’s also widely used in the biotechnology industry to produce biofuels, pharmaceuticals, and other high-value chemicals.

While researchers have previously rewritten the genomes of viruses and bacteria, yeast is more challenging because its DNA is split across 16 chromosomes. To speed up progress, the research groups involved each focused on rewriting a different chromosome, before trying to combine them. The team has now successfully synthesized new versions of all 16 chromosomes and created an entirely novel chromosome. In a series of papers in Cell and Cell Genomics, the team also reports the successful combination of seven of these synthetic chromosomes, plus a fragment of another, in a single cell. Altogether, they account for more than 50 percent of the cell’s DNA.

More here.

October War

Tim Sahay interviews Guy Laron in Polycrisis:

TIM SAHAY: Bibi Netenyahu is Israel’s longest serving prime minister, surviving many corruption scandals and public protests. In a tweet you said: “the Bibi doctrine has collapsed: it created a Hamas monster, Apartheid in the West Bank, and a hollow state. But he’s not letting go of his efforts to create a personalist dictatorship.” What is the Netanyahu doctrine? What are its bases of domestic support?

GUY LARON: It started in 2009, when Netanyahu came back to power. Nobody then thought that he would be in power this long. The starting point of the Bibi doctrine is neoliberalism. From that you can derive all other aspects of his policy. The doctrine is upheld by his domestic coalition. That is where his foreign policy begins. What he cares about is getting the support of two demographically ascending sectors of Israel’s society: the ultra-Orthodox and the settlers in the West Bank.

The ultra-Orthodox are not that important for his foreign policy, but they are important for his domestic policy. While the rest of society suffers cuts in spending for public health, public education, and public transport, the ultra-Orthodox are exempt from cuts.

Next is support for settlers in the West Bank. It’s an open secret that there is a welfare state in Israel, which exists only in the West Bank, and only for Jews. Each time Netanyahu wrote new legislation—to make the state smaller, the budget smaller, the taxes lighter—parties representing the ultra-Orthodox and the settlers supported him. In everything he does, then, Netanyahu needs to show settlers in the West Bank that he is meeting their needs.

This is where Hamas comes in.

More here.

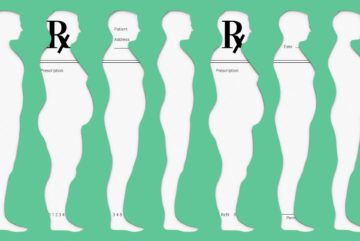

Should We End Obesity?

Jamie Ducharme in Time Magazine:

It’s unusual for a medication to become a household name; even more uncommon for its branding to become, like Advil, shorthand for an entire class of products; and rarest of all, for it to change not just U.S. medicine, but U.S. culture. Ozempic has done all three.

It’s unusual for a medication to become a household name; even more uncommon for its branding to become, like Advil, shorthand for an entire class of products; and rarest of all, for it to change not just U.S. medicine, but U.S. culture. Ozempic has done all three.

Approved in 2017 as a type 2 diabetes medication, Ozempic has largely made its name—and a fortune for its manufacturer, Novo Nordisk—as a weight-loss aid. Novo Nordisk knew early on that diabetes patients often lost weight on the drug, but even company executives couldn’t have guessed how widely it would eventually take off as both an off-label anti-obesity treatment and a vanity-driven status symbol for those simply looking to shed a few pounds. Its runaway success mirrors that of similar medications, including Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro and Wegovy, another Novo Nordisk product and the only one in the trio technically approved for weight loss. Prescriptions for all of them are flying off the pad at an eye-popping rate. Novo Nordisk sold around $14 billion of its various diabetes and obesity drugs in the first half of 2023, and Eli Lilly sold almost $1 billion worth of Mounjaro in a single quarter this year.

More here.

Friday, November 10, 2023

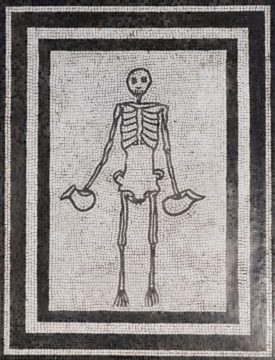

Birth, Death, and the Moveable Bookends of Personhood

Justin Smith-Ruiu in his Substack Newsletter:

We are coming up the seventh anniversary of my grandfather-in-law’s death. Traditionally, in the Orthodox church, this occasion would be marked by a ritual that involves digging up the bones of the deceased, washing them white and clean, and then reburying them forever. In the period prior to that significant anniversary, there is ongoing exchange, both ritual and spontaneous, with the dead. Whenever food or drink is accidentally spilled from the table, it is said to be shared with the dead. The candles lit for the dead outside of churches are another effective way of initiating exchange. Food, fire, and prayer continue to pass across the boundary that death has made impermeable to ordinary speech and action.

We are coming up the seventh anniversary of my grandfather-in-law’s death. Traditionally, in the Orthodox church, this occasion would be marked by a ritual that involves digging up the bones of the deceased, washing them white and clean, and then reburying them forever. In the period prior to that significant anniversary, there is ongoing exchange, both ritual and spontaneous, with the dead. Whenever food or drink is accidentally spilled from the table, it is said to be shared with the dead. The candles lit for the dead outside of churches are another effective way of initiating exchange. Food, fire, and prayer continue to pass across the boundary that death has made impermeable to ordinary speech and action.

It was only when my father died in 2016 that this deep truth of human existence hit me: there are two basic categories of people, the living and the dead, and the members of both categories are equally people. Some people are dead people, in other words.

More here.

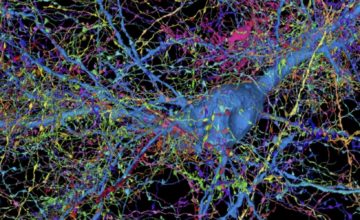

How AI could lead to a better understanding of the brain

Viren Jain in Nature:

Can a computer be programmed to simulate a brain? It’s a question mathematicians, theoreticians and experimentalists have long been asking — whether spurred by a desire to create artificial intelligence (AI) or by the idea that a complex system such as the brain can be understood only when mathematics or a computer can reproduce its behaviour. To try to answer it, investigators have been developing simplified models of brain neural networks since the 1940s1. In fact, today’s explosion in machine learning can be traced back to early work inspired by biological systems.

Can a computer be programmed to simulate a brain? It’s a question mathematicians, theoreticians and experimentalists have long been asking — whether spurred by a desire to create artificial intelligence (AI) or by the idea that a complex system such as the brain can be understood only when mathematics or a computer can reproduce its behaviour. To try to answer it, investigators have been developing simplified models of brain neural networks since the 1940s1. In fact, today’s explosion in machine learning can be traced back to early work inspired by biological systems.

However, the fruits of these efforts are now enabling investigators to ask a slightly different question: could machine learning be used to build computational models that simulate the activity of brains?

More here.

Ali Akbar Razi Qawwal: Gham e Hussain se Dil ko Hayat Milti Hai

Review of “How Migration Really Works” by Hein de Haas

Daniel Trilling in The Guardian:

Here’s a question for you: since the last general election, has the British government been tough or soft on immigration? Depending on your political inclination, the answer might seem obvious – but the reality is more complicated. On the one hand, the Johnson and Sunak governments have brought an end to EU free movement and promised to deport unwanted asylum seekers to Rwanda. On the other, net migration – the difference between the number of people coming to live in the UK and the number of people leaving – reached a record high of more than 600,000 last year.

Here’s a question for you: since the last general election, has the British government been tough or soft on immigration? Depending on your political inclination, the answer might seem obvious – but the reality is more complicated. On the one hand, the Johnson and Sunak governments have brought an end to EU free movement and promised to deport unwanted asylum seekers to Rwanda. On the other, net migration – the difference between the number of people coming to live in the UK and the number of people leaving – reached a record high of more than 600,000 last year.

Depending on your political inclination, this might seem like typical Tory hypocrisy, but the distinguished migration scholar Hein de Haas says it’s a contradiction that runs through governments across the west, no matter who is in charge. Since the second world war, according to a long-term study of data from 45 countries by de Haas and colleagues, immigration policies have tended to become more liberal. At the same time, border defences – in the form of walls and surveillance, or crackdowns on people-smuggling – have gone up. Between 2012 and 2022, for instance, the budget of the EU border agency Frontex rose from €85m to €754m.

The paradox arises, argues de Haas, because governments in the west – committed, as they are, to forms of economic liberalism – are constantly trying to balance three competing demands.

More here.

Hilary Putnam Interview – Mind, Truth & Science (1998)

Tomas Tranströmer’s Wild Associative Leaps.

Jared Marcel Pollen at Poetry Magazine:

Tranströmer has been praised for the apparent effortlessness of his craft. The poet and critic David Orr writes, “The typical Tranströmer poem is an exercise in sophisticated simplicity, in which relatively spare language acquires remarkable depth, and every word seems measured to the millimeter.” I think of his poetry as being like a Kagan couch, its upholstery fixed with a single staple, or a Newtonian bridge that needs no nails and is held together by the elegance of its stress equations. It is free of any superfluous furniture—“Truth doesn’t need any furniture,” Tranströmer writes in “Preludes.”

Tranströmer has been praised for the apparent effortlessness of his craft. The poet and critic David Orr writes, “The typical Tranströmer poem is an exercise in sophisticated simplicity, in which relatively spare language acquires remarkable depth, and every word seems measured to the millimeter.” I think of his poetry as being like a Kagan couch, its upholstery fixed with a single staple, or a Newtonian bridge that needs no nails and is held together by the elegance of its stress equations. It is free of any superfluous furniture—“Truth doesn’t need any furniture,” Tranströmer writes in “Preludes.”

But this risks making Tranströmer sound like a Swedish minimalist. Far from it: the poems gathered in this collection—spanning 50 years—are remarkably varied, incorporating prose poems, long lines, and haiku. They move easily from the idyll to the suburb, the cloudscape to the metro station, the nave to the waiting room, yet all bear what his friend Robert Bly—whose early translations were partly responsible for introducing Tranströmer’s work to English readers in the 1970s—described as his “strange genius for the image” and a “mystery and surprise [that] never fade, even on many readings.”

more here.

The Miracle of Photography

Ed Simon at The Millions:

More shadows than men, really; just silhouettes, might as well be smudges on the lens. Hard to notice at first, the two undifferentiated figures in the lower left-hand of the picture, at the corner of the Boulevard du Temple. A bootblack squats down and shines the shoes of a man contrapasso above him; impossible to tell what they’re wearing or what they look like. Obviously no way to ascertain their names or professions. At first they’re hard to recognize as people, these whispers of a figure joined together, eternally preserved by silver-plated copper and mercury vapor; they’re insignificant next to the buildings, elegant Beaux-Arts shops and theaters, wrought iron railings along the streets and chimneys on their mansard roofs. Based on an analysis of the light, Louis Daguerre set up his camera around eight in the morning; leaves are still on trees, so it’s not winter, but otherwise it’s hard to tell what season it is that Paris day in 1838. Whatever their names, it was by accident that they became the first two humans to be photographed.

More shadows than men, really; just silhouettes, might as well be smudges on the lens. Hard to notice at first, the two undifferentiated figures in the lower left-hand of the picture, at the corner of the Boulevard du Temple. A bootblack squats down and shines the shoes of a man contrapasso above him; impossible to tell what they’re wearing or what they look like. Obviously no way to ascertain their names or professions. At first they’re hard to recognize as people, these whispers of a figure joined together, eternally preserved by silver-plated copper and mercury vapor; they’re insignificant next to the buildings, elegant Beaux-Arts shops and theaters, wrought iron railings along the streets and chimneys on their mansard roofs. Based on an analysis of the light, Louis Daguerre set up his camera around eight in the morning; leaves are still on trees, so it’s not winter, but otherwise it’s hard to tell what season it is that Paris day in 1838. Whatever their names, it was by accident that they became the first two humans to be photographed.

more here.

Days of The Jackal: how Andrew Wylie turned serious literature into big business

Alex Blasdel in The Guardian:

Andrew Wylie, the world’s most renowned – and for a long time its most reviled – literary agent, is 76 years old. Over the past four decades, he has reshaped the business of publishing in profound and, some say, insalubrious ways. He has been a champion of highbrow books and unabashed commerce, making many great writers famous and many famous writers rich. In the process, he has helped to define the global literary canon. His critics argue that he has also hastened the demise of the literary culture he claims to defend. Wylie is largely untroubled by such criticisms. What preoccupies him, instead, are the deals to be made in China.

Andrew Wylie, the world’s most renowned – and for a long time its most reviled – literary agent, is 76 years old. Over the past four decades, he has reshaped the business of publishing in profound and, some say, insalubrious ways. He has been a champion of highbrow books and unabashed commerce, making many great writers famous and many famous writers rich. In the process, he has helped to define the global literary canon. His critics argue that he has also hastened the demise of the literary culture he claims to defend. Wylie is largely untroubled by such criticisms. What preoccupies him, instead, are the deals to be made in China.

Wylie’s fervour for China began in 2008, when a bidding war broke out among Chinese publishers for the collected works of Jorge Luis Borges. Wylie, who represents the Argentine master’s estate, received a telephone call from a colleague informing him that the price had climbed above $100,000, a hitherto inconceivable sum for a foreign literary work in China. Not content to just sit back and watch the price tick up, Wylie decided he would try to dictate the value of other foreign works in the Chinese market. “I thought, ‘We need to roll out the tanks,’” Wylie gleefully recounted in his New York offices earlier this year. “We need a Tiananmen Square!”

More here.

This hybrid baby monkey is made of cells from two embryos

Carissa Wong in Nature:

Scientists have created an infant ‘chimaeric’ monkey by injecting a monkey embryo with stem cells from a genetically distinct donor embryo1. The resulting animal is the first live-born chimaeric primate to have a high proportion of cells originating from donor stem cells.

Scientists have created an infant ‘chimaeric’ monkey by injecting a monkey embryo with stem cells from a genetically distinct donor embryo1. The resulting animal is the first live-born chimaeric primate to have a high proportion of cells originating from donor stem cells.

The finding, reported today in Cell, opens the door to using chimaeric monkeys, which are more biologically similar to humans than are chimaeric rats and mice, for studying human diseases and developing treatments, says stem-cell biologist Miguel Esteban at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences in Guangzhou, a co-author of the study. But the monkey chimaera had to be euthanized when it was only ten days old because of hypothermia and breathing difficulties, highlighting the need for further optimization of the approach and raising ethical concerns, say researchers.

More here.

Thursday, November 9, 2023

Salman Rushdie on peace, Barbie and what freedom cost him

Salman Rushdie in The Guardian:

I have always been inspired by mythologies, folktales and fairytales, not because they contain miracles – talking animals or magic fishes – but because they encapsulate truth. For example, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, which was an important inspiration for my novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet, can be told in fewer than 100 words, yet it contains, in compressed form, mighty questions about the relationship between art, love and death. It asks: can love, with the help of art, overcome death? But perhaps it answers: doesn’t death, in spite of art, overcome love? Or else it tells us that art takes on the subjects of love and death and transcends both by turning them into immortal stories. Those 100 words contain enough profundity to inspire 1,000 novels.

I have always been inspired by mythologies, folktales and fairytales, not because they contain miracles – talking animals or magic fishes – but because they encapsulate truth. For example, the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, which was an important inspiration for my novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet, can be told in fewer than 100 words, yet it contains, in compressed form, mighty questions about the relationship between art, love and death. It asks: can love, with the help of art, overcome death? But perhaps it answers: doesn’t death, in spite of art, overcome love? Or else it tells us that art takes on the subjects of love and death and transcends both by turning them into immortal stories. Those 100 words contain enough profundity to inspire 1,000 novels.

More here.

The Hidden Connection That Changed Number Theory

Max G. Levy in Quanta:

There are three kinds of prime numbers. The first is a solitary outlier: 2, the only even prime. After that, half the primes leave a remainder of 1 when divided by 4. The other half leave a remainder of 3. (5 and 13 fall in the first camp, 7 and 11 in the second.) There is no obvious reason that remainder-1 primes and remainder-3 primes should behave in fundamentally different ways. But they do.

There are three kinds of prime numbers. The first is a solitary outlier: 2, the only even prime. After that, half the primes leave a remainder of 1 when divided by 4. The other half leave a remainder of 3. (5 and 13 fall in the first camp, 7 and 11 in the second.) There is no obvious reason that remainder-1 primes and remainder-3 primes should behave in fundamentally different ways. But they do.

One key difference stems from a property called quadratic reciprocity, first proved by Carl Gauss, arguably the most influential mathematician of the 19th century. “It’s a fairly simple statement that has applications everywhere, in all sorts of math, not just number theory,” said James Rickards, a mathematician at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “But it’s also non-obvious enough to be really interesting.”

Number theory is a branch of mathematics that deals with whole numbers (as opposed to, say, shapes or continuous quantities). The prime numbers — those divisible only by 1 and themselves — are at its core, much as DNA is core to biology. Quadratic reciprocity has changed mathematicians’ conception of how much it’s possible to prove about them.

More here.

Queasy about lab-grown meat? Too bad — you’ve pretty much been eating it for decades

Garth Brown in The New Atlantis:

For the past century, agriculture in America has been getting more productive and more efficient. After stagnating for decades at twenty-something bushels per acre, average corn yields have risen to nearly two hundred. Horses have been replaced by horsepower. Chicken meat, once a relatively rare byproduct of the egg industry, has become the most consumed meat in the country, a shift made possible by advances in genetics and feed. Now over a billion dollars, from sources as varied as Bill Gates, venture capital funds, and agribusiness giants, have been invested in the idea that the next big thing in food is to leave farming behind, at least the livestock part of it. Instead of growing chicken meat in a chicken, why not grow it in a test tube?

For the past century, agriculture in America has been getting more productive and more efficient. After stagnating for decades at twenty-something bushels per acre, average corn yields have risen to nearly two hundred. Horses have been replaced by horsepower. Chicken meat, once a relatively rare byproduct of the egg industry, has become the most consumed meat in the country, a shift made possible by advances in genetics and feed. Now over a billion dollars, from sources as varied as Bill Gates, venture capital funds, and agribusiness giants, have been invested in the idea that the next big thing in food is to leave farming behind, at least the livestock part of it. Instead of growing chicken meat in a chicken, why not grow it in a test tube?

In June, U.S. regulators for the first time gave two California companies, Upside Foods and GOOD Meat, a green light for offering lab-grown chicken to American consumers, with star chef José Andrés becoming the first to cook it for his guests in July.

More here.