Andrew Deck in Rest of World:

A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as Scale AI and Appen, are recruiting poets, novelists, playwrights, or writers with a PhD or master’s degree. Dozens more seek general annotators with humanities degrees, or years of work experience in literary fields. The listings aren’t limited to English: Some are looking specifically for poets and fiction writers in Hindi and Japanese, as well as writers in languages less represented on the internet.

A string of job postings from high-profile training data companies, such as Scale AI and Appen, are recruiting poets, novelists, playwrights, or writers with a PhD or master’s degree. Dozens more seek general annotators with humanities degrees, or years of work experience in literary fields. The listings aren’t limited to English: Some are looking specifically for poets and fiction writers in Hindi and Japanese, as well as writers in languages less represented on the internet.

The companies say contractors will write short stories on a given topic to feed them into AI models. They will also use these workers to provide feedback on the literary quality of their current AI-generated text.

More here.

Deep in Pakistan’s countryside, Sindhi Chhokri and her teenage brother Toxic Sufi are raising a few eyebrows.

Deep in Pakistan’s countryside, Sindhi Chhokri and her teenage brother Toxic Sufi are raising a few eyebrows. In 1978, Kathy Kleiner was asleep in her bed at the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University when serial killer Ted Bundy entered through an unlocked door. After attacking two of her sorority sisters, Bundy found Kathy’s door also unlocked.

In 1978, Kathy Kleiner was asleep in her bed at the Chi Omega sorority house at Florida State University when serial killer Ted Bundy entered through an unlocked door. After attacking two of her sorority sisters, Bundy found Kathy’s door also unlocked.  We asked young scientists this question: If you could introduce any two scientists, regardless of where and when they lived, whom would you choose, and how would their collaboration change the course of history? Read a selection of the responses here. Follow NextGen Voices on social media with hashtag #NextGenSci.

We asked young scientists this question: If you could introduce any two scientists, regardless of where and when they lived, whom would you choose, and how would their collaboration change the course of history? Read a selection of the responses here. Follow NextGen Voices on social media with hashtag #NextGenSci.

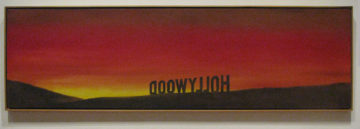

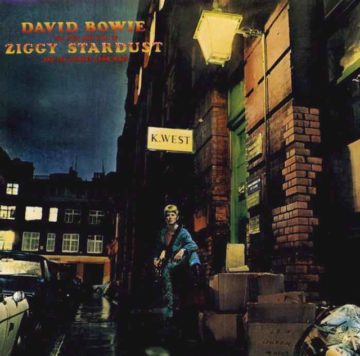

In a past life, he was an arsonist. A bold accusation, I realize, but nobody makes that many paintings, drawings, and photographs of fire without some buried lust for the real deal. By the time I left “Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” an XXL retrospective at moma comprising some two hundred works produced between the Eisenhower years and the present, I had lost count of the burning things, which are as lowbrow as a diner and as la-di-da as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The title of Ruscha’s 1964 photo series, “Various Small Fires and Milk,” could have been, minus the milk, a reasonable title for the exhibition itself, if he hadn’t painted various large ones, too.

In a past life, he was an arsonist. A bold accusation, I realize, but nobody makes that many paintings, drawings, and photographs of fire without some buried lust for the real deal. By the time I left “Ed Ruscha / Now Then,” an XXL retrospective at moma comprising some two hundred works produced between the Eisenhower years and the present, I had lost count of the burning things, which are as lowbrow as a diner and as la-di-da as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The title of Ruscha’s 1964 photo series, “Various Small Fires and Milk,” could have been, minus the milk, a reasonable title for the exhibition itself, if he hadn’t painted various large ones, too.

A famous

A famous  Right now, many forms of knowledge production seem to be facing their end. The crisis of the humanities has reached a tipping point of financial and popular disinvestment, while technological advances such as new artificial intelligence programmes may outstrip human ingenuity. As news outlets disappear, extreme political movements question the concept of objectivity and the scientific process. Many of our systems for producing and certifying knowledge have ended or are ending.

Right now, many forms of knowledge production seem to be facing their end. The crisis of the humanities has reached a tipping point of financial and popular disinvestment, while technological advances such as new artificial intelligence programmes may outstrip human ingenuity. As news outlets disappear, extreme political movements question the concept of objectivity and the scientific process. Many of our systems for producing and certifying knowledge have ended or are ending. R

R The word that comes to mind to describe all this—the light, the music, the sacred waters, the sacred garments—is “pilgrimage.” One rarely sees living writers treated with such reverence. “I am just a strange guy from the western part of Norway, from the rural part of Norway,” Fosse told me. He grew up a mixture of a communist and an anarchist, a “hippie” who loved playing the fiddle and reading in the countryside. He enrolled at the University of Bergen, where he studied comparative literature and started writing in Nynorsk, the written standard specific to the rural regions of the west. His first novel, “Red, Black,” was published in 1983, followed throughout the next three decades by “

The word that comes to mind to describe all this—the light, the music, the sacred waters, the sacred garments—is “pilgrimage.” One rarely sees living writers treated with such reverence. “I am just a strange guy from the western part of Norway, from the rural part of Norway,” Fosse told me. He grew up a mixture of a communist and an anarchist, a “hippie” who loved playing the fiddle and reading in the countryside. He enrolled at the University of Bergen, where he studied comparative literature and started writing in Nynorsk, the written standard specific to the rural regions of the west. His first novel, “Red, Black,” was published in 1983, followed throughout the next three decades by “ In more than 1,500 animal species, from crickets and sea urchins to bottlenose dolphins and bonobos, scientists have observed sexual encounters between members of the same sex. Some researchers have proposed that this behavior has existed

In more than 1,500 animal species, from crickets and sea urchins to bottlenose dolphins and bonobos, scientists have observed sexual encounters between members of the same sex. Some researchers have proposed that this behavior has existed  Using a host of high-tech tools to simulate brain development in a lab dish, Stanford University researchers have

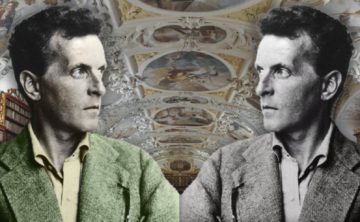

Using a host of high-tech tools to simulate brain development in a lab dish, Stanford University researchers have  Few philosophers have given rise to an entire movement, far fewer to two. Along with Heidegger, Wittgenstein counts among this select number in the 20th Century. Wittgenstein capped his early career with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a dense cryptic book whose truth he found “unassailable and definitive” in finding “on all essential points, the final solution of the problems” (T Preface)–until he came back years later to assail its solutions. He returned to give not just different solutions, but an entirely different take on the nature of knowledge, reality, and what philosophical views about such matters must be like. These two phases of his thought shaped much of roughly the first half of analytic philosophy’s history. The Tractatus brings Frege, Russell, and Moore’s logicism to its culmination and inspired the Vienna Circle. His later work, generally represented by the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, is a foundational work of the ordinary language philosophy practiced by Austin and Ryle and, despite his personal hostility to naturalism, contains elements that pushed analytic thought in that direction where Quine and others then took over. One of the central topics Wittgenstein changed his mind about was on the question of realism – whether we can know the world as it really is and whether our language can map onto reality.

Few philosophers have given rise to an entire movement, far fewer to two. Along with Heidegger, Wittgenstein counts among this select number in the 20th Century. Wittgenstein capped his early career with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a dense cryptic book whose truth he found “unassailable and definitive” in finding “on all essential points, the final solution of the problems” (T Preface)–until he came back years later to assail its solutions. He returned to give not just different solutions, but an entirely different take on the nature of knowledge, reality, and what philosophical views about such matters must be like. These two phases of his thought shaped much of roughly the first half of analytic philosophy’s history. The Tractatus brings Frege, Russell, and Moore’s logicism to its culmination and inspired the Vienna Circle. His later work, generally represented by the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, is a foundational work of the ordinary language philosophy practiced by Austin and Ryle and, despite his personal hostility to naturalism, contains elements that pushed analytic thought in that direction where Quine and others then took over. One of the central topics Wittgenstein changed his mind about was on the question of realism – whether we can know the world as it really is and whether our language can map onto reality. Our planet and its environment are in bad shape, in all sorts of ways. Those of us who want to improve the situation face a dilemma. On the one hand, we have to be forceful and clear-headed about how the bad the situation actually is. On the other, we don’t want to give the impression that things are so bad that it’s hopeless. That could — and, empirically, does — give people the impression that there’s no point in working to make things better. Hannah Ritchie is an environmental researcher at Our World in Data who wants to thread this needle: things are bad, but there are ways we can work to make them better.

Our planet and its environment are in bad shape, in all sorts of ways. Those of us who want to improve the situation face a dilemma. On the one hand, we have to be forceful and clear-headed about how the bad the situation actually is. On the other, we don’t want to give the impression that things are so bad that it’s hopeless. That could — and, empirically, does — give people the impression that there’s no point in working to make things better. Hannah Ritchie is an environmental researcher at Our World in Data who wants to thread this needle: things are bad, but there are ways we can work to make them better.