Avi Shafran in Tablet:

On July 16, 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer stood in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico, watching a second sunrise—that caused by the detonation of the world’s first nuclear explosion, marking the dawn of the atomic age. Standing by his side was I.I. Rabi, another Jewish physicist. “It was a vision,” Rabi later said of that explosion. “Then, a few minutes afterward, I had gooseflesh all over me when I realized what this meant for the future of humanity.” If Oppenheimer was the Jewish father of the bomb, it had a large assortment of Jewish uncles (and at least one aunt, Lise Meitner), including Edward Teller, Leo Szilard, Niels Bohr, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, John von Neuman, Rudolf Peierls, Franz Eugene Simon, Hans Halban, Joseph Rotblatt, Stanislav Ulam, Richard Feynman, and Eugene Wigner.

On July 16, 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer stood in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico, watching a second sunrise—that caused by the detonation of the world’s first nuclear explosion, marking the dawn of the atomic age. Standing by his side was I.I. Rabi, another Jewish physicist. “It was a vision,” Rabi later said of that explosion. “Then, a few minutes afterward, I had gooseflesh all over me when I realized what this meant for the future of humanity.” If Oppenheimer was the Jewish father of the bomb, it had a large assortment of Jewish uncles (and at least one aunt, Lise Meitner), including Edward Teller, Leo Szilard, Niels Bohr, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, John von Neuman, Rudolf Peierls, Franz Eugene Simon, Hans Halban, Joseph Rotblatt, Stanislav Ulam, Richard Feynman, and Eugene Wigner.

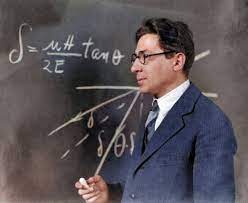

Judaism qua Judaism, however, wasn’t a major part of the lives of most, if not all, of those Jewish scientists. Certainly not of Oppenheimer’s. But Judaism was central for Rabi, who was a close colleague and friend of Oppenheimer’s, and who was vital to America’s efforts to develop the atomic bomb. In 1930, Rabi researched the nature of the force binding protons to atomic nuclei. That work eventually led to the creation of molecular-beam magnetic-resonance detection, for which Rabi was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1944. Rabi’s work is what made magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, the valuable diagnostic test, possible.

More here.