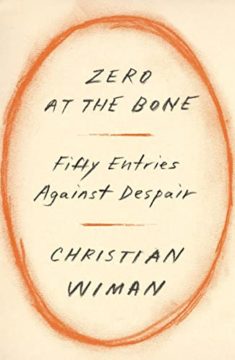

Alexandra Jacobs at the New York Times:

Much of “Zero at the Bone” is set a long way from Yale: in the hot, flat, scrubby towns of Texas where Wiman grew up, the apparent golden child of a deeply tarnished family, “my father vanishing, my mother wracked with rage and faith, my siblings sinking into drugs and alcohol, my own mind burning at night like an oil fire on water.” (He mentions only briefly an opiate addiction of his own, and spends maybe a little too much time recapping an abandoned bildungsroman in service of the theory that God is a failed novelist “who seems conflicted about how — or whether — to finish us.”)

Much of “Zero at the Bone” is set a long way from Yale: in the hot, flat, scrubby towns of Texas where Wiman grew up, the apparent golden child of a deeply tarnished family, “my father vanishing, my mother wracked with rage and faith, my siblings sinking into drugs and alcohol, my own mind burning at night like an oil fire on water.” (He mentions only briefly an opiate addiction of his own, and spends maybe a little too much time recapping an abandoned bildungsroman in service of the theory that God is a failed novelist “who seems conflicted about how — or whether — to finish us.”)

Along with humanity’s end in the main, Wiman has been forced to confront his own end in the particular. His refusal to submit to America’s “cancer camaraderie,” instead trying to explain the “otherworldly intimacy” of its pain, reminded me of Barbara Ehrenreich. “Through the rooms/the white minders come and go/with their upbeat and their bags of blood,” he writes Prufrockishly of hospital treatment.

more here.

In seventeen years it will be the 200

In seventeen years it will be the 200 R

R A little more than a year ago, the world seemed to wake up to the promise and dangers of artificial intelligence when OpenAI released

A little more than a year ago, the world seemed to wake up to the promise and dangers of artificial intelligence when OpenAI released  In Germany, public discussion of Hamas’s brutal October 7 attack and Israel’s devastating counterassault has been uniquely constrained. The horrors of the Shoah and the genocide of nearly six million Jews—nearly a third of the world Jewish population at the time—left German citizens with a singular burden of responsibility to ensure that the Jewish minority would never again be exposed to such crimes. Since its founding in 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany has upheld what amounts to an official policy of unequivocal support for Israel. This remains largely the case even today, despite marked changes in Israel’s political culture and the rise of far more militant voices on the religious right over the last few decades—voices that claim all territories (including both Gaza and the West Bank) for the Jews alone and at times have called for the expulsion of Palestinians, even the 20 percent who are officially Israeli citizens and have their own political parties.

In Germany, public discussion of Hamas’s brutal October 7 attack and Israel’s devastating counterassault has been uniquely constrained. The horrors of the Shoah and the genocide of nearly six million Jews—nearly a third of the world Jewish population at the time—left German citizens with a singular burden of responsibility to ensure that the Jewish minority would never again be exposed to such crimes. Since its founding in 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany has upheld what amounts to an official policy of unequivocal support for Israel. This remains largely the case even today, despite marked changes in Israel’s political culture and the rise of far more militant voices on the religious right over the last few decades—voices that claim all territories (including both Gaza and the West Bank) for the Jews alone and at times have called for the expulsion of Palestinians, even the 20 percent who are officially Israeli citizens and have their own political parties. The Irish singer and songwriter Shane MacGowan, a founding member of the punk-rock band the Pogues, died on Thursday, of pneumonia, at age sixty-five. It might sound as though he went young—and, by ordinary rubrics, he did—but MacGowan was a famously voracious consumer of drugs and prone to physical trauma. For decades, he flung himself around as though he were made of rubber. (“He was repeatedly injured in falls and struck by moving vehicles,” is how the Times put it in his

The Irish singer and songwriter Shane MacGowan, a founding member of the punk-rock band the Pogues, died on Thursday, of pneumonia, at age sixty-five. It might sound as though he went young—and, by ordinary rubrics, he did—but MacGowan was a famously voracious consumer of drugs and prone to physical trauma. For decades, he flung himself around as though he were made of rubber. (“He was repeatedly injured in falls and struck by moving vehicles,” is how the Times put it in his  What the hell is reality and how do we distinguish it from fiction? Who decides? Furthermore, if those who decide the allocations of the real and unreal are cruel, mad or colossally wrong, what then? These are the sorts of questions to which J G Ballard returns again and again in his fiction and non-fiction. His writing career spanned more than five decades. His work ranged from short stories published in New Worlds and Science Fantasy in the 1950s through to anti-realist novels exploring malfunctioning societies, psychological extremity, fragmentary modernity and technomania: from Crash! (1973), Concrete Island (1974), The Unlimited Dream Company (1979) to Rushing to Paradise (1994) and others. In later novels, such as Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), Ballard focused intently on savage anomie among the upper-middle classes, devising his own genre of bourgeois noir. Like Philip K Dick – who defined himself as ‘a fictionalising philosopher’ – Ballard deployed the creaking conventions of the novel to pose deep questions about reality, truth and the relationship between the inner mind and the external world. In his introduction to the French edition of Crash!, Ballard wrote: ‘The most prudent and effective method of dealing with the world around us is to assume that it is a complete fiction.’

What the hell is reality and how do we distinguish it from fiction? Who decides? Furthermore, if those who decide the allocations of the real and unreal are cruel, mad or colossally wrong, what then? These are the sorts of questions to which J G Ballard returns again and again in his fiction and non-fiction. His writing career spanned more than five decades. His work ranged from short stories published in New Worlds and Science Fantasy in the 1950s through to anti-realist novels exploring malfunctioning societies, psychological extremity, fragmentary modernity and technomania: from Crash! (1973), Concrete Island (1974), The Unlimited Dream Company (1979) to Rushing to Paradise (1994) and others. In later novels, such as Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), Ballard focused intently on savage anomie among the upper-middle classes, devising his own genre of bourgeois noir. Like Philip K Dick – who defined himself as ‘a fictionalising philosopher’ – Ballard deployed the creaking conventions of the novel to pose deep questions about reality, truth and the relationship between the inner mind and the external world. In his introduction to the French edition of Crash!, Ballard wrote: ‘The most prudent and effective method of dealing with the world around us is to assume that it is a complete fiction.’ WE LIVE IN CONFESSIONAL TIMES and the self-exposure bug eventually comes for us all, the steeliest of non-disclosers, no less. We age and turn inward, we become garrulous and spill. Even I, who once fled the first-person singular like a bad smell, now talk about myself endlessly in print, opening every essay or review with some “revealing” anecdote or slightly abashed confession, striving for the perfect degree of manicured self-deprecation and helpless charm. Needless to say, the more forthcoming you appear, the more calculated the agenda, not always consciously.

WE LIVE IN CONFESSIONAL TIMES and the self-exposure bug eventually comes for us all, the steeliest of non-disclosers, no less. We age and turn inward, we become garrulous and spill. Even I, who once fled the first-person singular like a bad smell, now talk about myself endlessly in print, opening every essay or review with some “revealing” anecdote or slightly abashed confession, striving for the perfect degree of manicured self-deprecation and helpless charm. Needless to say, the more forthcoming you appear, the more calculated the agenda, not always consciously. Evolution is a complicated thing. Much of modern evolutionary biology seeks to reconcile the seeming randomness of the forces behind the process — how mutations occur, for example — with the fundamental principles that apply across the biosphere. Generations of biologists have hoped to comprehend evolution’s rhyme and reason enough to be able to predict how it happens.

Evolution is a complicated thing. Much of modern evolutionary biology seeks to reconcile the seeming randomness of the forces behind the process — how mutations occur, for example — with the fundamental principles that apply across the biosphere. Generations of biologists have hoped to comprehend evolution’s rhyme and reason enough to be able to predict how it happens. In 1929, one of Germany’s national newspapers ran a picture story featuring globally influential people who, the headline proclaimed, “have become legends.” It included the former U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin and India’s anti-colonialist leader Mahatma Gandhi. Alongside them was a picture of a long-since-forgotten German poet. His name was Stefan George, but to those under his influence he was known as “Master.”

In 1929, one of Germany’s national newspapers ran a picture story featuring globally influential people who, the headline proclaimed, “have become legends.” It included the former U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin and India’s anti-colonialist leader Mahatma Gandhi. Alongside them was a picture of a long-since-forgotten German poet. His name was Stefan George, but to those under his influence he was known as “Master.” It is said that psychoanalysts see sex in everything, attributing any number of problems to unconscious sexual desires, but the British Lacanian psychoanalyst Darian Leader wonders if such desires are themselves cover for other motivations. As he puts it, what are we “actually doing when we are doing sex?” (“Doing” sex?) Urban legend has it that men think about sex every seven seconds; researchers have ascertained it’s more like every hour and a half – but even then, are sexy thoughts a diversion from other, unhappier ones? This might explain, for example, why porn use surges on a Sunday night and Monday, when we confront the work stress we’ve set aside for the weekend.

It is said that psychoanalysts see sex in everything, attributing any number of problems to unconscious sexual desires, but the British Lacanian psychoanalyst Darian Leader wonders if such desires are themselves cover for other motivations. As he puts it, what are we “actually doing when we are doing sex?” (“Doing” sex?) Urban legend has it that men think about sex every seven seconds; researchers have ascertained it’s more like every hour and a half – but even then, are sexy thoughts a diversion from other, unhappier ones? This might explain, for example, why porn use surges on a Sunday night and Monday, when we confront the work stress we’ve set aside for the weekend. Three versions of Gemini have been created for different applications, called Nano, Pro and Ultra, which increase in size and capability. Google declined to answer questions on the size of Pro and Ultra, the number of parameters they include or the scale or source of their training data. But its smallest version, Nano, which is designed to run locally on smartphones, is actually two models: one for slower phones that has 1.8 billion parameters and one for more powerful devices that has 3.25 billion parameters. Comparing the capabilities of AI models is an inexact science, but GPT-4 is rumoured to include up to 1.7 trillion parameters and Meta’s

Three versions of Gemini have been created for different applications, called Nano, Pro and Ultra, which increase in size and capability. Google declined to answer questions on the size of Pro and Ultra, the number of parameters they include or the scale or source of their training data. But its smallest version, Nano, which is designed to run locally on smartphones, is actually two models: one for slower phones that has 1.8 billion parameters and one for more powerful devices that has 3.25 billion parameters. Comparing the capabilities of AI models is an inexact science, but GPT-4 is rumoured to include up to 1.7 trillion parameters and Meta’s