Michelle Orange in Harper’s:

BID, body integrity dysphoria, is rare. Though experts are reluctant to estimate its prevalence, it is believed that at least a thousand people globally have the disorder. Medical recognition of the condition is growing, and its addition to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) took effect last year. The ICD defines BID as “an intense and persistent desire to become physically disabled in a significant way”—to become, for example, a major-limb amputee, paraplegic, or blind—“with onset by early adolescence accompanied by persistent discomfort, or intense feelings of inappropriateness” regarding one’s body.

BID, body integrity dysphoria, is rare. Though experts are reluctant to estimate its prevalence, it is believed that at least a thousand people globally have the disorder. Medical recognition of the condition is growing, and its addition to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) took effect last year. The ICD defines BID as “an intense and persistent desire to become physically disabled in a significant way”—to become, for example, a major-limb amputee, paraplegic, or blind—“with onset by early adolescence accompanied by persistent discomfort, or intense feelings of inappropriateness” regarding one’s body.

I learned of the ailment in 2011, the year that I met Dr. Michael First, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia and an editor of the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), who had inaugurated an earlier term for the condition, body integrity identity disorder, in a 2005 study. First was then campaigning for BIID to be added to the DSM-5—what remains the most recent edition—which was in its deliberative stage. I was writing about those deliberations, specifically about the various political and institutional follies involved in defining normalcy. I was preoccupied, as well, with our culture’s competing blights of self-focus and self-alienation, and a possible synergy between them; how easily our efforts toward perfection can turn destructive. At the time, BIID seemed the ne plus ultra of this danger, a useful metaphor for an age on the verge, one might say, of dismantling itself.

More here.

Our conveniently vague or unrealistic

Our conveniently vague or unrealistic  Did you know that sperm whales make sounds using “lips” located near their blowholes — and that those sounds are so loud they could burst the eardrums of a human diver at close range? Or that, near the start of the Covid-19 lockdowns in Britain in 2020, residents on newly quiet streets became aware of “noisy lovemaking” by amorous hedgehogs? Or that, according to legend, churchbells in the English coastal town of Dunwich, which largely disappeared into the sea following storm surges in the 14th century, can still be heard when the tide is just right?

Did you know that sperm whales make sounds using “lips” located near their blowholes — and that those sounds are so loud they could burst the eardrums of a human diver at close range? Or that, near the start of the Covid-19 lockdowns in Britain in 2020, residents on newly quiet streets became aware of “noisy lovemaking” by amorous hedgehogs? Or that, according to legend, churchbells in the English coastal town of Dunwich, which largely disappeared into the sea following storm surges in the 14th century, can still be heard when the tide is just right? Two years ago, I gave an academic talk via Zoom on the need to limit work in order to combat the culture of burnout in the United States. Following my presentation, a senior scholar had more of a comment than a question for me. He said that “we” needed to acknowledge our privileged status among workers. When academics criticize the American work ethic, he added, we ought to recognize that most workers “can’t afford to burn out.” Burnout, I took him to be saying, was a luxury, and to complain about it was like flaunting your wealth before someone desperately poor.

Two years ago, I gave an academic talk via Zoom on the need to limit work in order to combat the culture of burnout in the United States. Following my presentation, a senior scholar had more of a comment than a question for me. He said that “we” needed to acknowledge our privileged status among workers. When academics criticize the American work ethic, he added, we ought to recognize that most workers “can’t afford to burn out.” Burnout, I took him to be saying, was a luxury, and to complain about it was like flaunting your wealth before someone desperately poor. Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

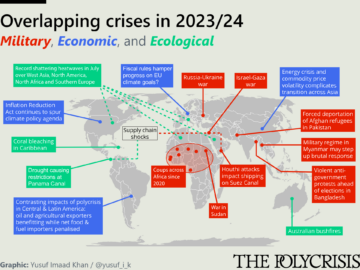

Tim Sahay in Polycrisis: I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older.

I HAVE FREQUENTLY BEEN SEATED in the dark near those who have variously been called “the pilly-sweater crowd,” “cinemaniacs,” or “Titus-heads” (referring to the two main movie theaters at MoMA). They are pejorative terms for a certain type of New York City cinephile, one whose zeal for the seventh art seems to have been leached of all pleasure and has instead transmogrified into grim compulsion. Demographically, they are often (but not always) white, male, and middle-aged or older. A

A I

I Ernest Becker was already dying when “The Denial of Death” was published 50 years ago this past fall. “This is a test of everything I’ve written about death,” he told a visitor to his Vancouver hospital room. Throughout his career as a cultural anthropologist, Becker had charted the undiscovered country that awaits us all. Now only 49 but losing a battle to colon cancer, he was being dispatched there himself. By the time his book was

Ernest Becker was already dying when “The Denial of Death” was published 50 years ago this past fall. “This is a test of everything I’ve written about death,” he told a visitor to his Vancouver hospital room. Throughout his career as a cultural anthropologist, Becker had charted the undiscovered country that awaits us all. Now only 49 but losing a battle to colon cancer, he was being dispatched there himself. By the time his book was  The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied.

The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied. Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable.

Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable.