Michele Gazzola in The Guardian:

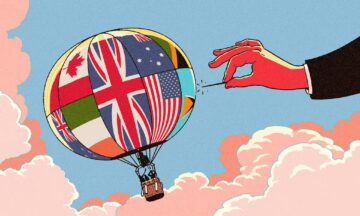

The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied.

The emergence of English as the predominant (though not exclusive) international language is seen by many as a positive phenomenon with several practical advantages and no downside. However, it also raises problems that are slowly beginning to be understood and studied.

The most important challenge is that of fairness or “linguistic justice”. A common language is a bit like a telephone network: the more people know a language, the more useful it becomes to communicate. The question of fairness arises because individuals face very different costs to access the network and are on an unequal footing when using it. Those who learn English as a second language incur learning costs, while native speakers can communicate with all network members without incurring such costs. It’s like getting the latest smartphone model and sim card with unlimited data for free.

François Grin, of the University of Geneva, estimates that western European countries spend between 5% and 15% of their education budget on foreign language teaching. In the EU, most of these resources go to the teaching of a single language, English.

More here.

Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable.

Some say that history begins with writing; we say that history begins with clothing. In the beginning, there was clothing made from skins that early humans removed from animals, processed, and then tailored to fit the human body; this technique is still used in the Arctic. Next came textiles. The first weavers would weave textiles in the shape of animal hides or raise the nap of the fabric’s surface to mimic the appearance of fur, making the fabric warmer and more comfortable. This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine.

This was during the Long 2010s (2009-2022), a decade during which there occurred more mass protests than any decade in history. The protests were against the usual suspects: capitalism, racism, imperialism, greed, corruption. Two new books, Vincent Bevins’s If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution and The Populist Moment: The Left After the Great Recession by Arthur Borriello and Anton Jäger, are about these protests and why they seemed to summon more of what they protested against—more greed, more racism, more corruption. They take different approaches. The Populist Moment is an academic investigation into the electoral failures of left-wing candidates in Europe and the United States (Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Jean-Luc Melenchon, Greece’s Syriza party), while If We Burn is a journalistic account of street protests in the Third World (Brazil, Indonesia, Chile) as well as Turkey and Ukraine. From a certain point of view, the extraordinary abundance of chickens might be seen as a positive development: Here is a source of protein that is cheaply produced, transportable, happily consumed by a huge number of people across the world. And thanks in part to Peterson’s efforts at improving feed conversion efficiency, chicken has a much slimmer carbon impact than beef, which contributes more than

From a certain point of view, the extraordinary abundance of chickens might be seen as a positive development: Here is a source of protein that is cheaply produced, transportable, happily consumed by a huge number of people across the world. And thanks in part to Peterson’s efforts at improving feed conversion efficiency, chicken has a much slimmer carbon impact than beef, which contributes more than  Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today.

Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today. A

A Wearing an electrode-studded cap bristling with wires, a young man silently reads a sentence in his head. Moments later, a Siri-like voice breaks in,

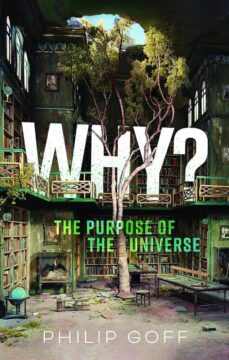

Wearing an electrode-studded cap bristling with wires, a young man silently reads a sentence in his head. Moments later, a Siri-like voice breaks in,  Why is there something rather than nothing? It’s meant to be the great unanswerable question. It’s certainly a poser. It would have been simpler if there’d been nothing: there wouldn’t be anything to explain.

Why is there something rather than nothing? It’s meant to be the great unanswerable question. It’s certainly a poser. It would have been simpler if there’d been nothing: there wouldn’t be anything to explain. For almost all of human existence, our species has been roaming the planet, living in small groups, hunting and gathering, moving to new areas when the climate was favourable, retreating when it turned nasty. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors used fire to cook and warm themselves. They made tools, shelters, clothing and jewellery – although their possessions were limited to what they could carry. They occasionally came across other hominins, like Neanderthals, and sometimes had sex with them. Across vast swathes of time, history played out, unrecorded.

For almost all of human existence, our species has been roaming the planet, living in small groups, hunting and gathering, moving to new areas when the climate was favourable, retreating when it turned nasty. For hundreds of thousands of years, our ancestors used fire to cook and warm themselves. They made tools, shelters, clothing and jewellery – although their possessions were limited to what they could carry. They occasionally came across other hominins, like Neanderthals, and sometimes had sex with them. Across vast swathes of time, history played out, unrecorded.

A specialist in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, Siegel has always been fascinated by perception: what and how we see, and the effect that has on what we can know. Her 2010 book, The Contents of Visual Experience, argued that conscious visual perception includes all kinds of complex properties: not just color, shape, light, and motion, but other, richer attributes, too. For instance, it encompasses what kind of thing we see—a tree, a bicycle, a dog?—and causal characteristics, like the property a knife can have while slicing through a piece of bread. Perception can even involve personal identity, Siegel argued: the property of being John Malkovich. The book’s central claim was that being able to visually recognize things, such as one’s own neighborhood, or pine trees, or John Malkovich, can influence how those things look to the person who sees them.

A specialist in epistemology and the philosophy of mind, Siegel has always been fascinated by perception: what and how we see, and the effect that has on what we can know. Her 2010 book, The Contents of Visual Experience, argued that conscious visual perception includes all kinds of complex properties: not just color, shape, light, and motion, but other, richer attributes, too. For instance, it encompasses what kind of thing we see—a tree, a bicycle, a dog?—and causal characteristics, like the property a knife can have while slicing through a piece of bread. Perception can even involve personal identity, Siegel argued: the property of being John Malkovich. The book’s central claim was that being able to visually recognize things, such as one’s own neighborhood, or pine trees, or John Malkovich, can influence how those things look to the person who sees them. Reclusive and disaffected, Ettore Majorana liked to work in the shadows. But after his friend Emilio Segrè dragged him into Enrico Fermi’s elite Roman physics club in the late 1920s, Majorana’s stature in atomic physics quickly grew. His mostly unpublished premonitions were eerily prescient: Among others, he famously intuited the existence of the neutron from prior experiments. And in 1937, he

Reclusive and disaffected, Ettore Majorana liked to work in the shadows. But after his friend Emilio Segrè dragged him into Enrico Fermi’s elite Roman physics club in the late 1920s, Majorana’s stature in atomic physics quickly grew. His mostly unpublished premonitions were eerily prescient: Among others, he famously intuited the existence of the neutron from prior experiments. And in 1937, he  HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or a mob boss who hasn’t got his hands dirty for decades. In his work, too, he offers little in the way of solace or solicitude, presenting a harsh world in parched prose.

HOW ROMANTIC IS J. M. COETZEE? At first the question, prompted by his eighteenth novel, The Pole, sounds like a joke. The journalist Rian Malan, who visited Coetzee’s office at the University of Cape Town in the early 1990s, reported that the novelist didn’t smoke, drink, eat meat, or, except on very rare occasions, laugh. “It helps to have a piercing gaze,” Coetzee wrote in one of eight essays on Beckett, and his own author photographs show a man who, with his ironed shirts, unvainly swept-back hair, and eyes that would win any no-blinking competition, resembles a semi-retired notary public, or a mob boss who hasn’t got his hands dirty for decades. In his work, too, he offers little in the way of solace or solicitude, presenting a harsh world in parched prose. Bella Baxter, the heroine of Poor Things in both the book and the film, often feels like one of those peculiar characters who appear in philosophy. In “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” for example, the Australian analytic philosopher Frank Jackson tells us about Mary, a brilliant scientist who “for whatever reason” has always lived inside a black and white room, learning everything about the world by watching a black and white television. What will happen, Jackson wonders, when we let her out—what knowledge will she gain when she sees the blue sky?

Bella Baxter, the heroine of Poor Things in both the book and the film, often feels like one of those peculiar characters who appear in philosophy. In “Epiphenomenal Qualia,” for example, the Australian analytic philosopher Frank Jackson tells us about Mary, a brilliant scientist who “for whatever reason” has always lived inside a black and white room, learning everything about the world by watching a black and white television. What will happen, Jackson wonders, when we let her out—what knowledge will she gain when she sees the blue sky?