Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

Tim Sahay in Polycrisis:

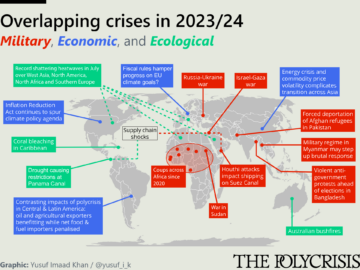

Global South left high and dry

A new Washington Consensus has arrived. Following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Biden officials from Jake Sullivan to Janet Yellen have emphasized that the world can and should follow the US in its new passion for productivism. Food and energy import bills are not only a climate problem, they point out, but a security concern. Indeed, nearly every import is increasingly scrutinized through a security lens, down to Chinese garlic.

The vision, then, is for localized, manufacturing-led green growth, erring on the side of redundancy rather than just-in-time production. All countries, the story goes, should be able to achieve prosperity through derisking, paired with local content restrictions, higher taxes, and subsidies for key sectors like clean energy, biotech and digital infrastructure.

There is only one small problem. After overhauling its internal investment regime, the US has thwarted any meaningful structural changes to the global financial architecture. On IMF quotas, voting shares, taxation, and even on its measly contribution to the new Loss and Damage Fund, the US has been conservative and isolationist. There have been a few consolation prizes—Barbados’s PM Mia Mottley won debt payment pauses for natural disasters; the IMF will give slightly more interest-free loans to low-income countries—but, on the whole, the global financial safety net continues to ensnare, rather than rescue, the most vulnerable countries.

More here.