Mosab Abu Toha in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

“Palestine is a story away.” This is what Refaat Alareer wrote on my copy of the short story anthology he edited in 2014, Gaza Writes Back. The contributors were his students at the Islamic University of Gaza.

“Palestine is a story away.” This is what Refaat Alareer wrote on my copy of the short story anthology he edited in 2014, Gaza Writes Back. The contributors were his students at the Islamic University of Gaza.

When I published my poetry book, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza, in 2022, the first person I gave a copy to in Gaza was Refaat. I signed the copy by writing, “Palestine is a poem away.”

Now Refaat is a world away. He was assassinated on December 6 by the Israeli army. The only weapon in his Gaza apartment was an EXPO marker. If the Israeli soldiers were to raid his house, he said, he would throw it at them, while crying, “We are helpless.”

Refaat and I loved strawberries. We used to go to Beit Lahia in North Gaza, pick strawberries, then sit and eat.

More here.

Every year at this time, people making resolutions look to self-help books to guide them in their new goals and ambitions. But our self-help is over-simplified easy optimism, a hangover from the days when How to Win Friends and Influence People defined the genre. It’s a mass of stoicism, wellbeing, minimalism, misunderstood Taoism, and productivity and habit advice. This sort of self-help can often be useful, but it is not a whole way of living. Rules for life and aphorisms are a starting point. The Ten Commandments are the original ten rules for life, but they came with the Bible, one of the largest, most challenging books ever written. The more accessible self-help becomes, the less useful it really is.

Every year at this time, people making resolutions look to self-help books to guide them in their new goals and ambitions. But our self-help is over-simplified easy optimism, a hangover from the days when How to Win Friends and Influence People defined the genre. It’s a mass of stoicism, wellbeing, minimalism, misunderstood Taoism, and productivity and habit advice. This sort of self-help can often be useful, but it is not a whole way of living. Rules for life and aphorisms are a starting point. The Ten Commandments are the original ten rules for life, but they came with the Bible, one of the largest, most challenging books ever written. The more accessible self-help becomes, the less useful it really is. In September, scientists at the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health

In September, scientists at the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health  Margaret Cavendish

Margaret Cavendish A

A MOST AMERICAN SCHOOLCHILDREN

MOST AMERICAN SCHOOLCHILDREN T

T

The British philosopher Gillian Rose, who advised the Polish government on how to redesign the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum after the fall of Communism, believed that the new regime of memory was mired in bad faith. By framing the Holocaust as an unfathomable evil — “the ultimate event, the ultimate mystery, never to be comprehended or transmitted,” as the writer Elie Wiesel once put it — we were protecting ourselves, Rose argued, from knowledge of our own capacity for barbarism. “Schindler’s List” was a case in point. For her, Spielberg’s black-and-white epic, which sentimentalizes the Jewish victims and keeps the Nazi perpetrators at arm’s length, was really just a piece of misty-eyed evasion.

The British philosopher Gillian Rose, who advised the Polish government on how to redesign the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum after the fall of Communism, believed that the new regime of memory was mired in bad faith. By framing the Holocaust as an unfathomable evil — “the ultimate event, the ultimate mystery, never to be comprehended or transmitted,” as the writer Elie Wiesel once put it — we were protecting ourselves, Rose argued, from knowledge of our own capacity for barbarism. “Schindler’s List” was a case in point. For her, Spielberg’s black-and-white epic, which sentimentalizes the Jewish victims and keeps the Nazi perpetrators at arm’s length, was really just a piece of misty-eyed evasion. Octopuses, artificial intelligence, and advanced alien civilizations: for many reasons, it’s interesting to contemplate ways of thinking other than whatever it is we humans do. How should we think about the space of all possible cognitions? One aspect is simply the physics of the underlying substrate, the physical stuff that is actually doing the thinking. We are used to brains being solid — squishy, perhaps, but consisting of units in an essentially fixed array. What about liquid brains, where the units can move around? Would an ant colony count? We talk with complexity theorist Ricard Solé about complexity, criticality, and cognition.

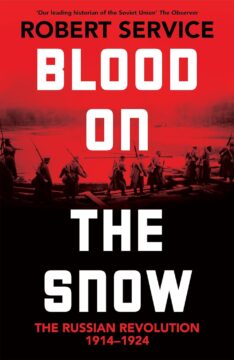

Octopuses, artificial intelligence, and advanced alien civilizations: for many reasons, it’s interesting to contemplate ways of thinking other than whatever it is we humans do. How should we think about the space of all possible cognitions? One aspect is simply the physics of the underlying substrate, the physical stuff that is actually doing the thinking. We are used to brains being solid — squishy, perhaps, but consisting of units in an essentially fixed array. What about liquid brains, where the units can move around? Would an ant colony count? We talk with complexity theorist Ricard Solé about complexity, criticality, and cognition. What we have here is the work of a lifetime, a reflective volume alert to local and geopolitics, art and culture, high society and the affairs of ordinary people. If he had served up a larger slice of history, encompassing the consolidation of Stalinism rather than ending the narrative with Lenin’s demise, he could have claimed with some justification to have written the definitive word on the revolution.

What we have here is the work of a lifetime, a reflective volume alert to local and geopolitics, art and culture, high society and the affairs of ordinary people. If he had served up a larger slice of history, encompassing the consolidation of Stalinism rather than ending the narrative with Lenin’s demise, he could have claimed with some justification to have written the definitive word on the revolution.