Category: Recommended Reading

Hegel’s World Revolutions

Terry Eagleton at the London Review of Books:

The Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle claimed he had once talked a student out of suicide by pointing out to him that the logic of ‘nothing matters’ is very different from that of, for example, ‘nothing chatters.’ For some who philosophise in this style, Hegel is not one of their tribe but an obscurantist, semi-mystical system-builder who ended up kowtowing to an autocratic Prussian state, and whose thought lies behind the totalitarianism of the 20th century. Philosophy consists in talking about certain things in a certain way; Hegel sometimes discusses the right kinds of thing (freedom, virtue, rationality), but doesn’t do so in the right kind of way. He writes about some subjects that don’t exist, such as the unity of identity and non-identity, as well as some that do (love, poverty, self-cultivation). But he wouldn’t count as philosophical at all for the likes of Ryle.

The Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle claimed he had once talked a student out of suicide by pointing out to him that the logic of ‘nothing matters’ is very different from that of, for example, ‘nothing chatters.’ For some who philosophise in this style, Hegel is not one of their tribe but an obscurantist, semi-mystical system-builder who ended up kowtowing to an autocratic Prussian state, and whose thought lies behind the totalitarianism of the 20th century. Philosophy consists in talking about certain things in a certain way; Hegel sometimes discusses the right kinds of thing (freedom, virtue, rationality), but doesn’t do so in the right kind of way. He writes about some subjects that don’t exist, such as the unity of identity and non-identity, as well as some that do (love, poverty, self-cultivation). But he wouldn’t count as philosophical at all for the likes of Ryle.

more here.

Ant Geopolitics

John Witfield at Aeon Magazine:

It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive.

It is a familiar story: a small group of animals living in a wooded grassland begin, against all odds, to populate Earth. At first, they occupy a specific ecological place in the landscape, kept in check by other species. Then something changes. The animals find a way to travel to new places. They learn to cope with unpredictability. They adapt to new kinds of food and shelter. They are clever. And they are aggressive.

In the new places, the old limits are missing. As their population grows and their reach expands, the animals lay claim to more territories, reshaping the relationships in each new landscape by eliminating some species and nurturing others. Over time, they create the largest animal societies, in terms of numbers of individuals, that the planet has ever known. And at the borders of those societies, they fight the most destructive within-species conflicts, in terms of individual fatalities, that the planet has ever known.

This might sound like our story: the story of a hominin species, living in tropical Africa a few million years ago, becoming global. Instead, it is the story of a group of ant species, living in Central and South America a few hundred years ago, who spread across the planet by weaving themselves into European networks of exploration, trade, colonisation and war – some even stowed away on the 16th-century Spanish galleons that carried silver across the Pacific from Acapulco to Manila.

more here.

Planet Ant: Life Inside the Colony

Wednesday Poem

Egyptian Archers

In Egyptian art, one archer stands

for all archers,

their contour drawn from his thigh, his shin, his chest,

his bow and quiver,

a deck of desires slightly spread.

Archers are technicians; this frieze

shows their discipline, how they draw

as one, their almond eye a blank,

calm as the strings unsmile,

sure of their mission

the moment their missiles

release.

They think: soon

I will recline with my lover and lyre again,

the bow’s tension gone,

the twang become strum

and gentle stroking, the hand that leads

not hungry for battle’s bloody plain, but

parting curtains, softly, to a bed

where my quiver will subside, incense slowly rise,

and the drum only of rain and conversation,

not war, nor plucked Assyrian eyes.

This arrow will save my life.

by Derek Webster

from Mockingbird

Véhicule Press, 2015

People Who Can’t Picture Sound in Their Minds

Ajdina Halilovic in Nautilus:

Jessie Donaldson has played the flute for 26 years. One of her favorite pieces to play is “Romance No. 2” by Beethoven, a sweet and stately composition for flute, oboes, bassoons, horns, and violin. But mentally rehearsing the flute part is tricky for the occupational therapist, who lives in Auckland, New Zealand. Jessie lacks the ability to simulate sounds in her mind. When I ask her to conjure the music that she has mastered over decades, she says she can feel the fingerings she has practiced, but can’t hear the parts in her mind’s ear. In those moments, Jessie’s mind is filled with thoughts of the rhythm and structure of the music but none of the actual sounds her flute or the other instruments produce.

Jessie Donaldson has played the flute for 26 years. One of her favorite pieces to play is “Romance No. 2” by Beethoven, a sweet and stately composition for flute, oboes, bassoons, horns, and violin. But mentally rehearsing the flute part is tricky for the occupational therapist, who lives in Auckland, New Zealand. Jessie lacks the ability to simulate sounds in her mind. When I ask her to conjure the music that she has mastered over decades, she says she can feel the fingerings she has practiced, but can’t hear the parts in her mind’s ear. In those moments, Jessie’s mind is filled with thoughts of the rhythm and structure of the music but none of the actual sounds her flute or the other instruments produce.

Going as far back as she can remember, this same silence permeates her memories, too. “I know what the sound of a laugh is,” she tells me, “but I can’t hear it in my mind. I have no memories with sounds.” Jessie only discovered that this was unusual when, by chance, she met a researcher who studies people like her.

More here.

Tina Turner – What’s Love Got To Do With It

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Tuesday, February 20, 2024

Marc Raibert: Boston Dynamics And The Future Of Robotics

Finding Footprints Laid At The Dawn Of Time

Mariana Petry Cabral at Sapiens:

Sitting on a log, in the ever-present shadow of the Amazon forest, Roseno Wajãpi and I shared pieces of cassava bread and chunks of smoked fish. He told me about the beginning of time.

Sitting on a log, in the ever-present shadow of the Amazon forest, Roseno Wajãpi and I shared pieces of cassava bread and chunks of smoked fish. He told me about the beginning of time.

Earth’s crust was recent, still in formation. Stones weren’t yet solid. Creator Hero Janejarã hiked between villages and sat down to rest at some spots. The rocks hardened, preserving both his footsteps and the imprint of his buttocks. Like many members of his community, the Wajãpi Indigenous people, Roseno can recognize these still-existing traces of Janejarã on the landscape.

Earlier that day, I had noticed some of Creator Hero’s footsteps by the river, but I interpreted the shallow, foot-long grooves differently. As an archaeologist, I assumed the smooth divots came from past people grinding cobbles against a rock surface to make stone axes.

more here.

Ash Wednesday

Sophie Haigney at The Paris Review:

I like the ashes on Ash Wednesday. I am at best a lapsed Catholic though it would be more accurate to say that I never really began, just that I was raised against the backdrop of already-faded-Catholicism and its associated traumas, now transmuted and passed on in their mysterious ways to me. I inherited also the pining and the predilection that many Americans have for certain things to do with Ireland. In San Francisco, I used to drink afternoons after I got off work at an Irish bar in Noe Valley, the Valley Tavern, or a different Irish bar downtown, the Chieftain, or sometimes come to think of it an Irish bar on Guerrero with big windows where my friend Graham and I used to like to watch the rain. San Francisco is a more Catholic city than most people think, and more Irish too. More Irish American, which is really what I am talking about: girls in red school uniforms and tennis shoes outside the Convent of the Sacred Heart, looking forward to football games Friday nights at St. Ignatius, the high school by the church where my feet were washed as a kid on Holy Thursday.

I like the ashes on Ash Wednesday. I am at best a lapsed Catholic though it would be more accurate to say that I never really began, just that I was raised against the backdrop of already-faded-Catholicism and its associated traumas, now transmuted and passed on in their mysterious ways to me. I inherited also the pining and the predilection that many Americans have for certain things to do with Ireland. In San Francisco, I used to drink afternoons after I got off work at an Irish bar in Noe Valley, the Valley Tavern, or a different Irish bar downtown, the Chieftain, or sometimes come to think of it an Irish bar on Guerrero with big windows where my friend Graham and I used to like to watch the rain. San Francisco is a more Catholic city than most people think, and more Irish too. More Irish American, which is really what I am talking about: girls in red school uniforms and tennis shoes outside the Convent of the Sacred Heart, looking forward to football games Friday nights at St. Ignatius, the high school by the church where my feet were washed as a kid on Holy Thursday.

more here.

Eugène-François Vidocq and the Birth of the Detective

Daisy Sainsbury at The Public Domain Review:

According to his memoirs, Eugène-François Vidocq escaped from more than twenty prisons (sometimes dressed as a nun). Working on the other side of the law, he apprehended some 4000 criminals with a team of plainclothes agents. He founded the first criminal investigation bureau — staffed mainly with convicts — and, when he was later fired, the first private detective agency. He was one the fathers of modern criminology and had a rap sheet longer than his very tall tales. Who was Vidocq?

According to his memoirs, Eugène-François Vidocq escaped from more than twenty prisons (sometimes dressed as a nun). Working on the other side of the law, he apprehended some 4000 criminals with a team of plainclothes agents. He founded the first criminal investigation bureau — staffed mainly with convicts — and, when he was later fired, the first private detective agency. He was one the fathers of modern criminology and had a rap sheet longer than his very tall tales. Who was Vidocq?

More here.

Mind-reading devices are revealing the brain’s secrets

Miryam Naddaf in Nature:

Moving a prosthetic arm. Controlling a speaking avatar. Typing at speed. These are all things that people with paralysis have learnt to do using brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) — implanted devices that are powered by thought alone. These devices capture neural activity using dozens to hundreds of electrodes embedded in the brain. A decoder system analyses the signals and translates them into commands. Although the main impetus behind the work is to help restore functions to people with paralysis, the technology also gives researchers a unique way to explore how the human brain is organized, and with greater resolution than most other methods.

Moving a prosthetic arm. Controlling a speaking avatar. Typing at speed. These are all things that people with paralysis have learnt to do using brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) — implanted devices that are powered by thought alone. These devices capture neural activity using dozens to hundreds of electrodes embedded in the brain. A decoder system analyses the signals and translates them into commands. Although the main impetus behind the work is to help restore functions to people with paralysis, the technology also gives researchers a unique way to explore how the human brain is organized, and with greater resolution than most other methods.

Scientists have used these opportunities to learn some basic lessons about the brain. Results are overturning assumptions about brain anatomy, for example, revealing that regions often have much fuzzier boundaries and job descriptions than was thought. Such studies are also helping researchers to work out how BCIs themselves affect the brain and, crucially, how to improve the devices. “BCIs in humans have given us a chance to record single-neuron activity for a lot of brain areas that nobody’s ever really been able to do in this way,” says Frank Willett, a neuroscientist at Stanford University in California who is working on a BCI for speech. The devices also allow measurements over much longer time spans than classical tools do, says Edward Chang, a neurosurgeon at the University of California, San Francisco. “BCIs are really pushing the limits, being able to record over not just days, weeks, but months, years at a time,” he says. “So you can study things like learning, you can study things like plasticity, you can learn tasks that require much, much more time to understand.”

More here.

The Met Aims to Get Harlem Right, the Second Time Around

Holland Cotter in The New York Times:

Notoriously, in the winter of 1969 the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its first exhibition devoted to African American culture, but with a show devoid of art. Called “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900—1968,” it was a photomural-with-texts affair of a kind found in ethnology museums.

Notoriously, in the winter of 1969 the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its first exhibition devoted to African American culture, but with a show devoid of art. Called “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900—1968,” it was a photomural-with-texts affair of a kind found in ethnology museums.

As a student in town on a visit, I wandered into the galleries, and even with scant knowledge of Black history, I knew something was off. I soon learned I wasn’t alone. The show was being slammed by pushback. A cohort of Black contemporary artists, some living and working in Harlem, calling themselves the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, had been picketing the museum, and directing their protest to other museums, lighting a fuse that would eventually detonate in the multicultural wave of the 1980s, with its demands for inclusion, and its affirmation of cultural identity, in art as in life, as a force.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Environmental DNA Is Everywhere and Scientists Are Gathering It All

Peter Andrey Smith in Undark:

eDNA serves as a surveillance tool, offering researchers a means of detecting the seemingly undetectable. By sampling eDNA, or mixtures of genetic material — that is, fragments of DNA, the blueprint of life — in water, soil, ice cores, cotton swabs, or practically any environment imaginable, even thin air, it is now possible to search for a specific organism or assemble a snapshot of all the organisms in a given place. Instead of setting up a camera to see who crosses the beach at night, eDNA pulls that information out of footprints in the sand. “We’re all flaky, right?” said Robert Hanner, a biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. “There’s bits of cellular debris sloughing off all the time.”

eDNA serves as a surveillance tool, offering researchers a means of detecting the seemingly undetectable. By sampling eDNA, or mixtures of genetic material — that is, fragments of DNA, the blueprint of life — in water, soil, ice cores, cotton swabs, or practically any environment imaginable, even thin air, it is now possible to search for a specific organism or assemble a snapshot of all the organisms in a given place. Instead of setting up a camera to see who crosses the beach at night, eDNA pulls that information out of footprints in the sand. “We’re all flaky, right?” said Robert Hanner, a biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. “There’s bits of cellular debris sloughing off all the time.”

More here.

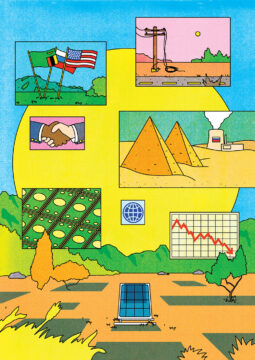

Why Isn’t Solar Scaling in Africa?

Todd Moss in Asterisk:

The solution seems so obvious. A region synonymous with abundant sun is hungry for more electricity. Given Africa’s colossal untapped solar radiation, the continent should be installing solar panels at a furious pace. But it’s not. Though home to 60% of the world’s best solar resources, Africa today represents just 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity.1 The entire region of 1.2 billion people has just one-fifth the solar capacity of cloudy, temperate Germany.

The solution seems so obvious. A region synonymous with abundant sun is hungry for more electricity. Given Africa’s colossal untapped solar radiation, the continent should be installing solar panels at a furious pace. But it’s not. Though home to 60% of the world’s best solar resources, Africa today represents just 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity.1 The entire region of 1.2 billion people has just one-fifth the solar capacity of cloudy, temperate Germany.

One sad tale begins with a high-profile initiative that explains a lot about Africa’s missing solar boom. In 2015, the private sector arm of the World Bank launched Scaling Solar to prove that bundling support for investments could blaze a trail to a solar future for everyone. Its first big project was impressive: Zambia, one of the world’s poorest countries, was able not only to attract private capital but also to slash costs for power by more than 80%. Scaling Solar’s next project in Senegal came in even cheaper. Then a 2019 solar farm in Uzbekistan was even lower. And then … nothing.

Scaling Solar did not scale. By the narrowest of measures, the initiative’s own project pipeline dried up.

More here.

Dan Dennett speaks to Richard Dawkins about the Evolution of Language & AI

Tuesday Poem

Brown Small Bird

The Nightingale will always be a mythical bird.

Did you ever see one outside poetry?

The Nightingale is named into anonymity, like a Monk,

like the celebrated girl who is only beautiful.

What a different thing it was when

Wild-Bird took

actual berries from my hand.

Blessed, I wanted statues made of it, a

city named, or something

Brown, small, bird.

Not to be known by his name anymore

than you, or me

by Lew Welsh

from Ring of Bone

Grey Fox Press,1979

Sunday, February 18, 2024

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Art

William Deresiewicz in Salmagundi:

Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.”

Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.”

Art is for truth. Even Wilde suggests as much, though he, and we, don’t call it truth but meaning. Art points beyond itself. At what? At us. The role of art is to compile the endless atlas of human experience. It’s often not a pretty picture for, as Solzhenitsyn said, the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. Except it’s not a line; it’s a tangle. The gurus want to solve human nature; so do the utopians, the ideologues and revolutionaries. The artist, wiser, observes it, above all in herself.

More here.

Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong – The Nearness Of You

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Hatred Alone Is Immortal

Alan Jacobs in The Hedgehog Review:

Many Americans, as far as I can tell, don’t want to shape their views in accordance with the data; many Americans, again as far as I can tell, don’t want to create an environment in which a broad range of perspectives are freely articulated and peacefully debated. They don’t want to be hopeful about the possibilities of America. Nor do they want academic freedom in our universities. What many people want, what they earnestly and passionately desire, is to hate their enemies. A few years ago J.D. Vance—now a senator, then a political neophyte—uttered The Creed of Our Age: “I think our people hate the right people.”

Many Americans, as far as I can tell, don’t want to shape their views in accordance with the data; many Americans, again as far as I can tell, don’t want to create an environment in which a broad range of perspectives are freely articulated and peacefully debated. They don’t want to be hopeful about the possibilities of America. Nor do they want academic freedom in our universities. What many people want, what they earnestly and passionately desire, is to hate their enemies. A few years ago J.D. Vance—now a senator, then a political neophyte—uttered The Creed of Our Age: “I think our people hate the right people.”

And that’s why the essential text for our time is an essay written almost exactly two hundred years ago by the English writer William Hazlitt: “On the Pleasure of Hating.”

More here.