Francesca Wade at The Nation:

In an anonymously published essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” George Eliot set out her objections to “mind-and-millinery” novels: those books featuring dazzling heroines—eloquent, accomplished, almost godly—who set off into the world solely in pursuit of an amiable husband. Castigating the genre for its “drivelling” narratives, clichéd characters, and hackneyed morals, Eliot argued that novels that posit marriage as a woman’s ultimate aim and achievement only “confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women.” In her own writing, Eliot set out not just to rehash the “marriage plot” but to expose and dissect it: Her sweeping novels show her utterly human characters grappling with the harsh disparities between societal expectations of married life and their own, often painful experiences of it.

In an anonymously published essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” George Eliot set out her objections to “mind-and-millinery” novels: those books featuring dazzling heroines—eloquent, accomplished, almost godly—who set off into the world solely in pursuit of an amiable husband. Castigating the genre for its “drivelling” narratives, clichéd characters, and hackneyed morals, Eliot argued that novels that posit marriage as a woman’s ultimate aim and achievement only “confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women.” In her own writing, Eliot set out not just to rehash the “marriage plot” but to expose and dissect it: Her sweeping novels show her utterly human characters grappling with the harsh disparities between societal expectations of married life and their own, often painful experiences of it.

As Clare Carlisle shows in her fascinating new biography, The Marriage Question, Eliot chose to make her life, as well as her fiction, outside the conventions of the marriage plot.

more here.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after melodrama had its heyday in the mid-19th century, it began to be mocked for being obsolete. In an 1890 burlesque of Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, the play later adapted into a more famous opera, the police chief Scarpia proudly admits that, as a villain intent on “possess[ing]” the play’s titular heroine, he is a vestige of “that dark age / when curdling melodrama held the stage.” Belonging to a genre that has come to feel more campy than poignant, even villains like Scarpia can’t take themselves seriously. And yet, no matter how many generations have claimed to have evolved away from a genre besmirched for its expressive storytelling and moral polarities, melodrama has retained its power as a way for artists to represent the world and as a lens for critics to interpret what they see.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after melodrama had its heyday in the mid-19th century, it began to be mocked for being obsolete. In an 1890 burlesque of Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, the play later adapted into a more famous opera, the police chief Scarpia proudly admits that, as a villain intent on “possess[ing]” the play’s titular heroine, he is a vestige of “that dark age / when curdling melodrama held the stage.” Belonging to a genre that has come to feel more campy than poignant, even villains like Scarpia can’t take themselves seriously. And yet, no matter how many generations have claimed to have evolved away from a genre besmirched for its expressive storytelling and moral polarities, melodrama has retained its power as a way for artists to represent the world and as a lens for critics to interpret what they see. In antiquity humans were referred to as “mortals,” which meant that they were destined not only to die but also to suffer loss, misfortune, and disaster. By comparison with the immortal gods, even the loftiest mortals are losers in the long run (as Achilles realizes in Hades). In his book In Praise of Failure, the philosopher and essayist Costica Bradatan reminds us that we flash into existence between “two instantiations of nothingness,” namely the nothingness before we were born and the one after we die. Each one of us, ontologically speaking, is next to nothing. And each one of us, despite our precarious condition, has something to lose. “Myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature”—all, according to Bradatan, seek to make our next-to-nothingness “a little more bearable.”

In antiquity humans were referred to as “mortals,” which meant that they were destined not only to die but also to suffer loss, misfortune, and disaster. By comparison with the immortal gods, even the loftiest mortals are losers in the long run (as Achilles realizes in Hades). In his book In Praise of Failure, the philosopher and essayist Costica Bradatan reminds us that we flash into existence between “two instantiations of nothingness,” namely the nothingness before we were born and the one after we die. Each one of us, ontologically speaking, is next to nothing. And each one of us, despite our precarious condition, has something to lose. “Myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature”—all, according to Bradatan, seek to make our next-to-nothingness “a little more bearable.” Decades ago, I argued that indeterminacy of interpretation, construed in the terminology of Husserl’s phenomenology and Saussure’s conception of language, was very close to Derrida’s “deconstruction.” I have come to see that the very structure of Davidson’s account of language commits him to a version of “dissemination,” the fluidity and “play” of ascriptions of meaning. The core of Davidson’s account of language and interpretation guarantees that natural languages will be disseminative.

Decades ago, I argued that indeterminacy of interpretation, construed in the terminology of Husserl’s phenomenology and Saussure’s conception of language, was very close to Derrida’s “deconstruction.” I have come to see that the very structure of Davidson’s account of language commits him to a version of “dissemination,” the fluidity and “play” of ascriptions of meaning. The core of Davidson’s account of language and interpretation guarantees that natural languages will be disseminative. Don’t impress me with peasant virtues, said Chekhov, I have peasant blood in my veins. Patrick Joyce has the blood too. His people won a living from the hard lands of Dúiche Seoighe, or Joyce Country, which stretch from Loughs Corrib and Mask to the Atlantic Ocean and straddle the border of County Mayo and County Galway. Although his father took the family to England in 1930, he brought his sons back every year and they would fall asleep night after night listening to kitchen talk in English and Irish. Joyce knows what he is talking about, and if his peasants are not always virtuous, they are at least vivid and real.

Don’t impress me with peasant virtues, said Chekhov, I have peasant blood in my veins. Patrick Joyce has the blood too. His people won a living from the hard lands of Dúiche Seoighe, or Joyce Country, which stretch from Loughs Corrib and Mask to the Atlantic Ocean and straddle the border of County Mayo and County Galway. Although his father took the family to England in 1930, he brought his sons back every year and they would fall asleep night after night listening to kitchen talk in English and Irish. Joyce knows what he is talking about, and if his peasants are not always virtuous, they are at least vivid and real. There is a well-known passage in

There is a well-known passage in  A new tech ideology is ascendant online. “Introducing effective accelerationism,” the pseudonymous user Beff Jezos tweeted, rather grandly, in May 2022. “E/acc” — pronounced ee-ack — “is a direct product [of the] tech Twitter schizosphere,” he wrote. “We hope you join us in this new endeavour.”

A new tech ideology is ascendant online. “Introducing effective accelerationism,” the pseudonymous user Beff Jezos tweeted, rather grandly, in May 2022. “E/acc” — pronounced ee-ack — “is a direct product [of the] tech Twitter schizosphere,” he wrote. “We hope you join us in this new endeavour.” From John Maynard Keynes’s prediction of a fifteen-hour workweek to Walt Disney’s Tomorrowland to 2001: A Space Odyssey’s interplanetary waltzing, many futurists and crystal-ball seers of the twentieth century assured us that, thanks to the wonders of technology, things were looking up for the human race. And remarkably, they were often justified in their buoyancy: President Kennedy explained in 1962 why we chose to go to the Moon, and seven years later there we were. Surely the 2000s would be a whole century of roaring twenties.

From John Maynard Keynes’s prediction of a fifteen-hour workweek to Walt Disney’s Tomorrowland to 2001: A Space Odyssey’s interplanetary waltzing, many futurists and crystal-ball seers of the twentieth century assured us that, thanks to the wonders of technology, things were looking up for the human race. And remarkably, they were often justified in their buoyancy: President Kennedy explained in 1962 why we chose to go to the Moon, and seven years later there we were. Surely the 2000s would be a whole century of roaring twenties. F

F One of the great 20th-Century novelists, Morrison consciously aimed her work at black American readers.

One of the great 20th-Century novelists, Morrison consciously aimed her work at black American readers. Wolin’s project can be summarized as follows: After the recent publication of Heidegger’s seminars, lectures, correspondence, and the Black Notebooks has revealed the Heideggerian edifice to be in ruins, Wolin wants to show that Heidegger’s writings can nonetheless provide philosophy with valuable material that can be re-used. Should we conclude that Wolin—like Trawny, Nancy, and di Cesare before him—seeks to salvage the seemingly valuable philosophical remains of Heideggerian thought following the publication of the Black Notebooks? And that this rescue operation is carried out in the face of opposition from mysterious and anonymous critical “commentators”? Or are these statements rhetorical, designed to safeguard the project against potential attacks by the most uncompromising of Heideggerians? It is in any case striking that Wolin places his project under the aegis of Nietzsche, given his previous unsparing criticism of this figure. He might argue that this is merely ironic. Yet the methodological fact remains that the Nietzsche citation fits with Wolin’s aim of re-evaluating the Heideggerian material.

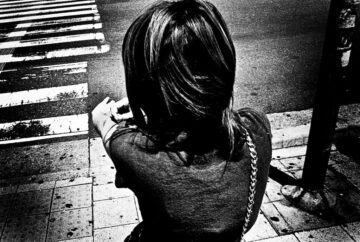

Wolin’s project can be summarized as follows: After the recent publication of Heidegger’s seminars, lectures, correspondence, and the Black Notebooks has revealed the Heideggerian edifice to be in ruins, Wolin wants to show that Heidegger’s writings can nonetheless provide philosophy with valuable material that can be re-used. Should we conclude that Wolin—like Trawny, Nancy, and di Cesare before him—seeks to salvage the seemingly valuable philosophical remains of Heideggerian thought following the publication of the Black Notebooks? And that this rescue operation is carried out in the face of opposition from mysterious and anonymous critical “commentators”? Or are these statements rhetorical, designed to safeguard the project against potential attacks by the most uncompromising of Heideggerians? It is in any case striking that Wolin places his project under the aegis of Nietzsche, given his previous unsparing criticism of this figure. He might argue that this is merely ironic. Yet the methodological fact remains that the Nietzsche citation fits with Wolin’s aim of re-evaluating the Heideggerian material. To encounter the work of Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama is to see the world not through his eyes but through his whole being. His angles are dizzyingly extreme, as if shot from the perspective of his knees, his toes, the back of his head. His subjects are blurred and warped, conjuring a sense of frenetic movement through space. His images—mostly black-and-white—are intensely high contrast, evocative of the sun’s unforgiving glare or the heightened realm of dreams. Rather than proposing an artfully constructed vision of the world, his photographs (whether of television screens or thronging beaches or fishnet-sheathed legs or discarded dolls) attempt to embody the fragmented experience of existence: its chaos, its precariousness, its fundamental inscrutability.

To encounter the work of Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama is to see the world not through his eyes but through his whole being. His angles are dizzyingly extreme, as if shot from the perspective of his knees, his toes, the back of his head. His subjects are blurred and warped, conjuring a sense of frenetic movement through space. His images—mostly black-and-white—are intensely high contrast, evocative of the sun’s unforgiving glare or the heightened realm of dreams. Rather than proposing an artfully constructed vision of the world, his photographs (whether of television screens or thronging beaches or fishnet-sheathed legs or discarded dolls) attempt to embody the fragmented experience of existence: its chaos, its precariousness, its fundamental inscrutability.