From the Boston Review:

In 2007 Louise Glück selected Fady Joudah as the winner of the distinguished Yale Series of Younger Poets competition. In a foreword to his debut poetry collection published the following year, The Earth in the Attic, she called Joudah a “lyric poet in whom circumstance and profession . . . have compelled obsession with large social contexts and grave national dilemmas.” Since then, Joudah has published five more collections of poetry, won numerous awards, and translated several volumes of poetry by Palestinian writers, among them Mahmoud Darwish, perhaps the best-known Palestinian poet in the English-speaking world.

In 2007 Louise Glück selected Fady Joudah as the winner of the distinguished Yale Series of Younger Poets competition. In a foreword to his debut poetry collection published the following year, The Earth in the Attic, she called Joudah a “lyric poet in whom circumstance and profession . . . have compelled obsession with large social contexts and grave national dilemmas.” Since then, Joudah has published five more collections of poetry, won numerous awards, and translated several volumes of poetry by Palestinian writers, among them Mahmoud Darwish, perhaps the best-known Palestinian poet in the English-speaking world.

Born in Texas to parents of the Palestinian diaspora, Joudah spent his early life in Libya and Saudi Arabia before returning to the United States to complete medical training. He now lives in Houston, where he works as an internal medicine physician while continuing to publish poetry.

More here.

“Where’s my tail?”

“Where’s my tail?” T

T It’s true that Caravaggio’s reputation as a revolutionary force in Italian art remains unmatched, but Artemisia Gentileschi now overshadows all the other artists who drew on his influence. Édouard Manet, likewise, may still be seen as the key figure in the emergence of modernism in 19th-century Paris, but among those who recognized and built on his achievement, Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot appear far more important today than they did 50 years ago; the specific qualities of their work, unshared by their contemporaries, have come into focus. Paula Modersohn-Becker outshines most of her German Expressionist colleagues. And while Jackson Pollock remains the Abstract Expressionist par excellence, Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell are now better appreciated than some of the male painters who were once accounted as his near-equals—Franz Kline, for example. Is just plain old “great” not great enough without the “supremely” added like a cherry on top?

It’s true that Caravaggio’s reputation as a revolutionary force in Italian art remains unmatched, but Artemisia Gentileschi now overshadows all the other artists who drew on his influence. Édouard Manet, likewise, may still be seen as the key figure in the emergence of modernism in 19th-century Paris, but among those who recognized and built on his achievement, Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot appear far more important today than they did 50 years ago; the specific qualities of their work, unshared by their contemporaries, have come into focus. Paula Modersohn-Becker outshines most of her German Expressionist colleagues. And while Jackson Pollock remains the Abstract Expressionist par excellence, Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell are now better appreciated than some of the male painters who were once accounted as his near-equals—Franz Kline, for example. Is just plain old “great” not great enough without the “supremely” added like a cherry on top? When my kids were little, I was always afraid that they would die, but that was mostly nervous ignorance on my part, knowing nothing about the resilience of little bodies. I used to worry how an infant would be able to tell me what was wrong. But the real worry was about my parents. They had language—and still they would die.

When my kids were little, I was always afraid that they would die, but that was mostly nervous ignorance on my part, knowing nothing about the resilience of little bodies. I used to worry how an infant would be able to tell me what was wrong. But the real worry was about my parents. They had language—and still they would die. In a recent interview with U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Elon Musk

In a recent interview with U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Elon Musk  Very few of us expected liberalism to have such a rocky

Very few of us expected liberalism to have such a rocky  When most people think of the civil rights movement, they think of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, and his acceptance of the Peace Prize the following year, secured his place as the voice of non-violent, mass protest in the 1960s. Yet the movement achieved its greatest results—the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act—due to the competing and sometimes radical strategies and agendas of diverse individuals such as Malcolm X, whose birthday is celebrated on May 19. As one of the most powerful, controversial, and enigmatic figures of the movement he occupies a necessary place in social studies/history curricula.

When most people think of the civil rights movement, they think of Martin Luther King, Jr., whose “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, and his acceptance of the Peace Prize the following year, secured his place as the voice of non-violent, mass protest in the 1960s. Yet the movement achieved its greatest results—the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act—due to the competing and sometimes radical strategies and agendas of diverse individuals such as Malcolm X, whose birthday is celebrated on May 19. As one of the most powerful, controversial, and enigmatic figures of the movement he occupies a necessary place in social studies/history curricula. Although the Cather nuts among us are puzzled that she is not taught, and therefore read, as much as, say, Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Cather has actually had plenty of biographical and scholarly attention since her death in 1947. Within six years, her lifelong companion and literary executrix Edith Lewis had brought out Willa Cather Living: A Personal Record (Knopf, 1953), and her friend Elizabeth Sergeant produced Willa Cather: A Memoir (Lippincott, 1953). That same year, Knopf published E. K. Brown’s Willa Cather: A Critical Biography, a work authorized by Lewis and finished by Leon Edel when Professor Brown died young and in harness. In 1970, James Woodress contributed Willa Cather: Her Life and Art, a wonderful if briefish study, to something called the Pegasus American Authors series. In 1986 Oxford University Press published Sharon O’Brien’s Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice, and the 1980s also saw both a full-length biography from Woodress from the University of Nebraska Press and a definitive full treatment from the British critic and literary biographer Hermione Lee (Willa Cather: Double Lives) from Pantheon. Cather has also in recent decades been the subject of considerations at various lengths by Joan Acocella, Vivian Gornick, Toni Morrison, Katherine Anne Porter, Phyllis Rose, and Eudora Welty, among others. Clearly, she has always been a writer’s writer.

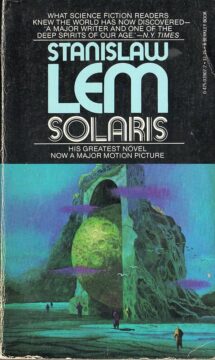

Although the Cather nuts among us are puzzled that she is not taught, and therefore read, as much as, say, Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Cather has actually had plenty of biographical and scholarly attention since her death in 1947. Within six years, her lifelong companion and literary executrix Edith Lewis had brought out Willa Cather Living: A Personal Record (Knopf, 1953), and her friend Elizabeth Sergeant produced Willa Cather: A Memoir (Lippincott, 1953). That same year, Knopf published E. K. Brown’s Willa Cather: A Critical Biography, a work authorized by Lewis and finished by Leon Edel when Professor Brown died young and in harness. In 1970, James Woodress contributed Willa Cather: Her Life and Art, a wonderful if briefish study, to something called the Pegasus American Authors series. In 1986 Oxford University Press published Sharon O’Brien’s Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice, and the 1980s also saw both a full-length biography from Woodress from the University of Nebraska Press and a definitive full treatment from the British critic and literary biographer Hermione Lee (Willa Cather: Double Lives) from Pantheon. Cather has also in recent decades been the subject of considerations at various lengths by Joan Acocella, Vivian Gornick, Toni Morrison, Katherine Anne Porter, Phyllis Rose, and Eudora Welty, among others. Clearly, she has always been a writer’s writer. In “Summa Technologiae,” Lem emphasizes how humanity, in thinking about the future, has often thought through the wrong questions. We can transmute other metals into gold now, but it was a misunderstanding that made us think we would still want to, he says. We can fly, but not by flapping our arms, since “even if we ourselves choose our end point, our way of getting there is chosen by Nature.” When Lem writes in “Summa” about artificial intelligence—or “intelligence amplifiers,” as he terms it—he says it’s likely possible that one day there will be an artificial intelligence ten thousand times smarter than us, but it won’t come from more advanced mathematics or algorithms. Instead, it comes from machines that can learn in a way similar to how we do—which is what is happening. With the Electronic Bard, Lem derides the worry that our own human creativity will be dwarfed. That, like the questions of the alchemists, he suggests, is the wrong concern. But what is the right one?

In “Summa Technologiae,” Lem emphasizes how humanity, in thinking about the future, has often thought through the wrong questions. We can transmute other metals into gold now, but it was a misunderstanding that made us think we would still want to, he says. We can fly, but not by flapping our arms, since “even if we ourselves choose our end point, our way of getting there is chosen by Nature.” When Lem writes in “Summa” about artificial intelligence—or “intelligence amplifiers,” as he terms it—he says it’s likely possible that one day there will be an artificial intelligence ten thousand times smarter than us, but it won’t come from more advanced mathematics or algorithms. Instead, it comes from machines that can learn in a way similar to how we do—which is what is happening. With the Electronic Bard, Lem derides the worry that our own human creativity will be dwarfed. That, like the questions of the alchemists, he suggests, is the wrong concern. But what is the right one? W

W On a recent October morning, Rob Kirby stood in front of a roomful of mathematicians and told them not to feel bound by the way he’d done things in the past.

On a recent October morning, Rob Kirby stood in front of a roomful of mathematicians and told them not to feel bound by the way he’d done things in the past. Asterisk: The overarching question in your transit policy career has been: Why is America so bad at building transit systems? Earlier this year, your team at NYU released a massive report comparing transit costs in Istanbul, Italy, Sweden and Boston, and then, of course, New York. It culminates in your fantastic case study of the Second Avenue subway line. And that’s where I wanted to start. What went wrong?

Asterisk: The overarching question in your transit policy career has been: Why is America so bad at building transit systems? Earlier this year, your team at NYU released a massive report comparing transit costs in Istanbul, Italy, Sweden and Boston, and then, of course, New York. It culminates in your fantastic case study of the Second Avenue subway line. And that’s where I wanted to start. What went wrong?