Elizabeth Winkler in The Guardian:

Scholars often say that no one doubted Shakespeare’s authorship until the 19th century. The response is a rote way of brushing off persistent questions about the attribution of the world’s most famous plays and poems – but it may not be true. New scholarship suggests that doubts about Shakespeare’s authorship first arose during his lifetime – in a book called Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury, published in 1598 by the theologian Francis Meres. Roger Stritmatter, a professor at Coppin State University who has spent years studying Meres’ book, argues that Meres asserted “Shakespeare” as the pseudonym of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Stritmatter’s research has been published in the academic journal Critical Survey. Shakespeare scholar Graham Holderness, who edited the journal, worries that shutting down debate about the authorship endangers academic freedom. “When you come across traditional Shakespeareans comparing Shakespeare authorship doubt to conspiracy theories – anti-vaxxers or climate change deniers – I mean, I think that’s wrong … for all sorts of reasons”, he said.

Scholars often say that no one doubted Shakespeare’s authorship until the 19th century. The response is a rote way of brushing off persistent questions about the attribution of the world’s most famous plays and poems – but it may not be true. New scholarship suggests that doubts about Shakespeare’s authorship first arose during his lifetime – in a book called Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury, published in 1598 by the theologian Francis Meres. Roger Stritmatter, a professor at Coppin State University who has spent years studying Meres’ book, argues that Meres asserted “Shakespeare” as the pseudonym of Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Stritmatter’s research has been published in the academic journal Critical Survey. Shakespeare scholar Graham Holderness, who edited the journal, worries that shutting down debate about the authorship endangers academic freedom. “When you come across traditional Shakespeareans comparing Shakespeare authorship doubt to conspiracy theories – anti-vaxxers or climate change deniers – I mean, I think that’s wrong … for all sorts of reasons”, he said.

Palladis Tamia is a “commonplace book” of sayings and comparisons. It has long been known to scholars as an essential text in Shakespeare studies. In a chapter titled, A Comparative Discourse of Our English Poets, with the Greeke, Latine, and Italian Poets, Meres compares English writers with classical writers using an as-so equation. For example: “As the soul of Euphorbus was thought to live in Pythagorus, so the sweet, witty soul of Ovid lives in mellifluous and honey-tongued Shakespeare.”

More here.

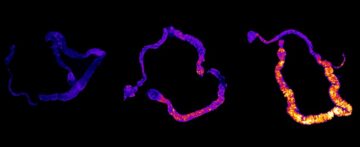

No one wants to eat when they have an upset stomach. To pinpoint exactly where in the brain this distaste for eating originates, scientists studied nauseated mice. The work, published in Cell Reports on 27 March

No one wants to eat when they have an upset stomach. To pinpoint exactly where in the brain this distaste for eating originates, scientists studied nauseated mice. The work, published in Cell Reports on 27 March E

E The attempts I made to get out of my own head were sundry and full of nonsense.

The attempts I made to get out of my own head were sundry and full of nonsense. Record rainfall hit the Arabian peninsula this week, causing flooding in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, as well as other coastal cities in the United Arab Emirates. The extreme weather prompted speculation on social media about whether the UAE’s longstanding cloud-seeding programme played a role. But cloud seeding almost certainly didn’t have any significant hand in the flooding.

Record rainfall hit the Arabian peninsula this week, causing flooding in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, as well as other coastal cities in the United Arab Emirates. The extreme weather prompted speculation on social media about whether the UAE’s longstanding cloud-seeding programme played a role. But cloud seeding almost certainly didn’t have any significant hand in the flooding. To be sure, AI models are evolving rapidly. When EU regulators released the first draft of the AI Act in April 2021, they

To be sure, AI models are evolving rapidly. When EU regulators released the first draft of the AI Act in April 2021, they  The first signs of insufficient sleep are universally familiar. There’s tiredness and fatigue, difficulty concentrating, perhaps irritability or even tired giggles. Far fewer people have experienced the effects of prolonged sleep deprivation, including disorientation, paranoia and hallucinations. Total, prolonged sleep deprivation, however, can be fatal. While it has been reported in humans only anecdotally, a

The first signs of insufficient sleep are universally familiar. There’s tiredness and fatigue, difficulty concentrating, perhaps irritability or even tired giggles. Far fewer people have experienced the effects of prolonged sleep deprivation, including disorientation, paranoia and hallucinations. Total, prolonged sleep deprivation, however, can be fatal. While it has been reported in humans only anecdotally, a  Toward the end of Percival Everett’s 2021 novel

Toward the end of Percival Everett’s 2021 novel  Angie calls in a high state of excitement: they’re going to see Elvis at Madison Square Garden in New York City. “Come over, David must look wonderful!” I want to go with them…there’s no chance of that happening, but still, a girl can dream. As I drive to Haddon Hall, I can’t help but think over and over…they’re going to see ELVIS!

Angie calls in a high state of excitement: they’re going to see Elvis at Madison Square Garden in New York City. “Come over, David must look wonderful!” I want to go with them…there’s no chance of that happening, but still, a girl can dream. As I drive to Haddon Hall, I can’t help but think over and over…they’re going to see ELVIS! What is the distance between the scent of a rose and the odour of camphor? Are floral smells perpendicular to smoky ones? Is the geometry of ‘odour space’ Euclidean, following the rules about lines, shapes and angles that decorate countless high-school chalkboards? To many, these will seem like either unserious questions or, less charitably, meaningless ones. Geometry is logic made visible, after all; the business of drawing unassailable conclusions from clearly stated axioms. And odour is, let’s be honest, a bit too vague and vaporous for any of that. The folksy idea of smell as the blunted and structureless sense is at least as old as Plato, and I have to confess that, even as an olfactory researcher, I sometimes feel like I’m studying the Pluto of the sensory systems – a shadowy, out-there iceball on a weird orbit.

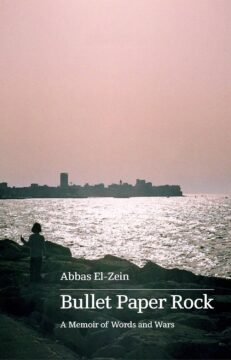

What is the distance between the scent of a rose and the odour of camphor? Are floral smells perpendicular to smoky ones? Is the geometry of ‘odour space’ Euclidean, following the rules about lines, shapes and angles that decorate countless high-school chalkboards? To many, these will seem like either unserious questions or, less charitably, meaningless ones. Geometry is logic made visible, after all; the business of drawing unassailable conclusions from clearly stated axioms. And odour is, let’s be honest, a bit too vague and vaporous for any of that. The folksy idea of smell as the blunted and structureless sense is at least as old as Plato, and I have to confess that, even as an olfactory researcher, I sometimes feel like I’m studying the Pluto of the sensory systems – a shadowy, out-there iceball on a weird orbit. Arabic speakers are spoilt for choice when it comes to expressions of love. At least twenty-five Arabic words for different shades of love, affection and love-induced states of mind are in common usage, by my count. The actual number is said to be somewhere between fifty and one hundred, if formal Arabic words, less encountered in day-to-day speech, are included.

Arabic speakers are spoilt for choice when it comes to expressions of love. At least twenty-five Arabic words for different shades of love, affection and love-induced states of mind are in common usage, by my count. The actual number is said to be somewhere between fifty and one hundred, if formal Arabic words, less encountered in day-to-day speech, are included. Writing explicitly about sex is provocative. Being too interested in food would be tacky, domestic. Debré’s narrator is comfortable with the upper classes and the down-and-out—“when your parents are upper-class junkies, you get good training”—but with Agnès has her first experience of a member of the “petty bourgeoisie.” She’s cast off the comforts of her class position, but she’s still rich on the inside. She tries to get used to Agnès’s mannerisms—the phrases like “Oh shoot” and “the little ones,” the habit of taking one’s shoes off at the door—and can’t. She admits to speaking with a “snobby accent.” She’s related to duchesses on her mother’s side; her grandfather on her father’s side was the prime minister. (Debré doesn’t spell it out, but the reference is to Michel Debré, who held office for three years under de Gaulle, and drafted the Constitution of the Fifth Republic.) She loves filthy language, and bourgeois striving and planning make no sense to her. She lives cheaply and insists that her change of station involves real risk, casting aspersion on the middle-class assumption that “when your family name’s in the dictionary you must automatically have money invested in mutual funds.” She writes that making money “stresses me out,” that “it’s only when I’m poor and the bailiffs are on my ass that I feel like I’m where I belong.” She seeks extremity. But no bailiff actually comes to call. She’s “so rich that I don’t care about being poor.”

Writing explicitly about sex is provocative. Being too interested in food would be tacky, domestic. Debré’s narrator is comfortable with the upper classes and the down-and-out—“when your parents are upper-class junkies, you get good training”—but with Agnès has her first experience of a member of the “petty bourgeoisie.” She’s cast off the comforts of her class position, but she’s still rich on the inside. She tries to get used to Agnès’s mannerisms—the phrases like “Oh shoot” and “the little ones,” the habit of taking one’s shoes off at the door—and can’t. She admits to speaking with a “snobby accent.” She’s related to duchesses on her mother’s side; her grandfather on her father’s side was the prime minister. (Debré doesn’t spell it out, but the reference is to Michel Debré, who held office for three years under de Gaulle, and drafted the Constitution of the Fifth Republic.) She loves filthy language, and bourgeois striving and planning make no sense to her. She lives cheaply and insists that her change of station involves real risk, casting aspersion on the middle-class assumption that “when your family name’s in the dictionary you must automatically have money invested in mutual funds.” She writes that making money “stresses me out,” that “it’s only when I’m poor and the bailiffs are on my ass that I feel like I’m where I belong.” She seeks extremity. But no bailiff actually comes to call. She’s “so rich that I don’t care about being poor.” T

T I

I