Simon Schuster in Time:

In Russian custom, the soul of the dead is believed to remain on earth for forty days, finishing its business among the living before it moves on to the afterlife. Surviving friends and relatives often spend this period in mourning and reflection. But the loved ones of Alexei Navalny, Russia’s leading dissident, did not have much freedom to abide by this custom after he died in an Arctic prison camp on February 16.

In Russian custom, the soul of the dead is believed to remain on earth for forty days, finishing its business among the living before it moves on to the afterlife. Surviving friends and relatives often spend this period in mourning and reflection. But the loved ones of Alexei Navalny, Russia’s leading dissident, did not have much freedom to abide by this custom after he died in an Arctic prison camp on February 16.

For them, and especially for his wife, Yulia Navalnaya, the days and weeks that followed his death rushed by in a blur of studio lights, airport terminals, hotel rooms and video calls. Somewhere in that time, between consoling their two children and being consoled by them, she met with President Joe Biden in San Francisco and addressed the European parliament in Strasbourg. She accused Vladimir Putin of killing her husband, and she implored the Russian people to help her get revenge. Along the way, to the surprise of many of her husband’s followers, Navalnaya took on a role she had never occupied before — no longer the first lady of the Russian opposition, but now its figurehead.

More here.

An experimental drug already tested as a potential treatment for cancer, lung disease, and

An experimental drug already tested as a potential treatment for cancer, lung disease, and  Last May, nine months after the knife attack that nearly killed him, Salman Rushdie made a surprise appearance at the 2023 PEN America literary gala. His voice was weak and he was noticeably thinner than usual; one of his eyeglass lenses was blacked out, because his right eye had been blinded in the assault. But anyone wondering whether the author was still his old exuberant self would have been immediately reassured by the way he began his remarks, with a racy impromptu joke.

Last May, nine months after the knife attack that nearly killed him, Salman Rushdie made a surprise appearance at the 2023 PEN America literary gala. His voice was weak and he was noticeably thinner than usual; one of his eyeglass lenses was blacked out, because his right eye had been blinded in the assault. But anyone wondering whether the author was still his old exuberant self would have been immediately reassured by the way he began his remarks, with a racy impromptu joke. In January 2022, researchers at OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT,

In January 2022, researchers at OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT,  As an investigative journalist, I write about war, weapons, national security and government secrets. I’ve previously written six books about US military and intelligence programmes – at the CIA, The Pentagon, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency– all designed to prevent, or deter,

As an investigative journalist, I write about war, weapons, national security and government secrets. I’ve previously written six books about US military and intelligence programmes – at the CIA, The Pentagon, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency– all designed to prevent, or deter,  Returning home after being away for any length of time is strange. The Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta, who journeyed 70,000 miles across much of the 14th-century Islamic world, wrote that “traveling gives you home in a thousand strange places, then leaves you a stranger in your own land.” I’d venture that all travelers, whether they have been away for years, months or only weeks, know something of this estrangement. What gap year student hasn’t returned from their rite-of-passage journey to find that the “gap” now lies between them and their former life? This peculiar dislocation — a kind of out-of-body experience — might wear off after several days, or it might last much longer.

Returning home after being away for any length of time is strange. The Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta, who journeyed 70,000 miles across much of the 14th-century Islamic world, wrote that “traveling gives you home in a thousand strange places, then leaves you a stranger in your own land.” I’d venture that all travelers, whether they have been away for years, months or only weeks, know something of this estrangement. What gap year student hasn’t returned from their rite-of-passage journey to find that the “gap” now lies between them and their former life? This peculiar dislocation — a kind of out-of-body experience — might wear off after several days, or it might last much longer. Determining whether someone has Alzheimer’s disease usually requires an extended diagnostic process. A doctor takes a patient’s medical history, discusses symptoms, administers verbal and visual cognitive tests. The patient may undergo a PET scan, an M.R.I. or a spinal tap — tests that detect the presence of two proteins in the brain, amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both associated with Alzheimer’s. All of that could change dramatically if new criteria proposed by an Alzheimer’s Association working group are widely adopted. Its final recommendations, expected later this year, will accelerate a shift that is already underway: from defining the disease by symptoms and behavior to defining it purely biologically — with biomarkers, substances in the body that indicate disease.

Determining whether someone has Alzheimer’s disease usually requires an extended diagnostic process. A doctor takes a patient’s medical history, discusses symptoms, administers verbal and visual cognitive tests. The patient may undergo a PET scan, an M.R.I. or a spinal tap — tests that detect the presence of two proteins in the brain, amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both associated with Alzheimer’s. All of that could change dramatically if new criteria proposed by an Alzheimer’s Association working group are widely adopted. Its final recommendations, expected later this year, will accelerate a shift that is already underway: from defining the disease by symptoms and behavior to defining it purely biologically — with biomarkers, substances in the body that indicate disease. While one segment of Silicon Valley lamented the perpetual absence of flying cars, another, it turns out, was quietly building them—or, at least, something flying-car adjacent. Just three months after the Founders Fund manifesto appeared, a Canadian inventor named Marcus Leng invited his neighbors and a couple of friends to his rural property, north of Lake Ontario. Leng was in his early fifties, with a bowl cut of coarse graying hair. He instructed his guests to park their (conventional) cars in a row and cower behind them. He strapped on a helmet and boarded a device that he’d built in his basement. It had a narrow single-seat chassis and two fixed wings, one in front and one in back, each with four small propellers. It was at once sleek and ungainly, as if a baby orca had been hitched to two snowplows. Observers described it, for lack of a better comparison, as looking like a U.F.O. Leng called it the BlackFly.

While one segment of Silicon Valley lamented the perpetual absence of flying cars, another, it turns out, was quietly building them—or, at least, something flying-car adjacent. Just three months after the Founders Fund manifesto appeared, a Canadian inventor named Marcus Leng invited his neighbors and a couple of friends to his rural property, north of Lake Ontario. Leng was in his early fifties, with a bowl cut of coarse graying hair. He instructed his guests to park their (conventional) cars in a row and cower behind them. He strapped on a helmet and boarded a device that he’d built in his basement. It had a narrow single-seat chassis and two fixed wings, one in front and one in back, each with four small propellers. It was at once sleek and ungainly, as if a baby orca had been hitched to two snowplows. Observers described it, for lack of a better comparison, as looking like a U.F.O. Leng called it the BlackFly. The two weeks spanning the O. J. Simpson verdict and Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March on Washington were a good time for connoisseurs of racial paranoia. As blacks exulted at Simpson’s acquittal, horrified whites had a fleeting sense that this race thing was knottier than they’d ever supposed—that, when all the pieties were cleared away, blacks really were strangers in their midst. (The unspoken sentiment: And I thought I knew these people.) There was the faintest tincture of the Southern slaveowner’s disquiet in the aftermath of the bloody slave revolt led by Nat Turner—when the gentleman farmer was left to wonder which of his smiling, servile retainers would have slit his throat if the rebellion had spread as was intended, like fire on parched thatch. In the day or so following the verdict, young urban professionals took note of a slight froideur between themselves and their nannies and babysitters—the awkwardness of an unbroached subject. Rita Dove, who recently completed a term as the United States Poet Laureate, and who believes that Simpson was guilty, found it “appalling that white people were so outraged—more appalling than the decision as to whether he was guilty or not.” Of course, it’s possible to overstate the tensions. Marsalis invokes the example of team sports, saying, “You want your side to win, whatever the side is going to be. And the thing is, we’re still at a point in our national history where we look at each other as sides.”

The two weeks spanning the O. J. Simpson verdict and Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March on Washington were a good time for connoisseurs of racial paranoia. As blacks exulted at Simpson’s acquittal, horrified whites had a fleeting sense that this race thing was knottier than they’d ever supposed—that, when all the pieties were cleared away, blacks really were strangers in their midst. (The unspoken sentiment: And I thought I knew these people.) There was the faintest tincture of the Southern slaveowner’s disquiet in the aftermath of the bloody slave revolt led by Nat Turner—when the gentleman farmer was left to wonder which of his smiling, servile retainers would have slit his throat if the rebellion had spread as was intended, like fire on parched thatch. In the day or so following the verdict, young urban professionals took note of a slight froideur between themselves and their nannies and babysitters—the awkwardness of an unbroached subject. Rita Dove, who recently completed a term as the United States Poet Laureate, and who believes that Simpson was guilty, found it “appalling that white people were so outraged—more appalling than the decision as to whether he was guilty or not.” Of course, it’s possible to overstate the tensions. Marsalis invokes the example of team sports, saying, “You want your side to win, whatever the side is going to be. And the thing is, we’re still at a point in our national history where we look at each other as sides.” Walnuts can

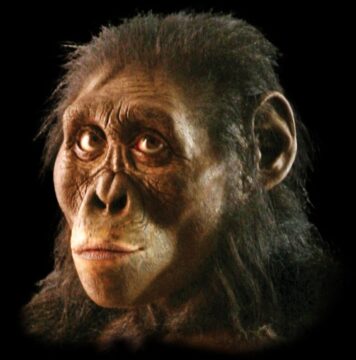

Walnuts can  Zeresenay Alemseged doesn’t remember the 1974 discovery of the famous fossil Lucy at Hadar in Ethiopia, because he was 5 years old, living 600 kilometers away in Axum. Later he saw Lucy’s name on cafes and taxis, but he knew little about her until he became a geologist working at the National Museum of Ethiopia. Then, she changed his life. In 2000, Alemseged was swept into Lucy’s orbit:

Zeresenay Alemseged doesn’t remember the 1974 discovery of the famous fossil Lucy at Hadar in Ethiopia, because he was 5 years old, living 600 kilometers away in Axum. Later he saw Lucy’s name on cafes and taxis, but he knew little about her until he became a geologist working at the National Museum of Ethiopia. Then, she changed his life. In 2000, Alemseged was swept into Lucy’s orbit:  Geoff Dyer: Yeah, it’s a little piece of self-encouragement. Because, you know, sometimes I’m sort of worried about my take on a given subject. Do I know enough about it? Take for example, my history of photography called The Ongoing Moment. I wrote that book because I wanted to find out about the history of photography. I wrote the book for the same reason that readers might later go to it.

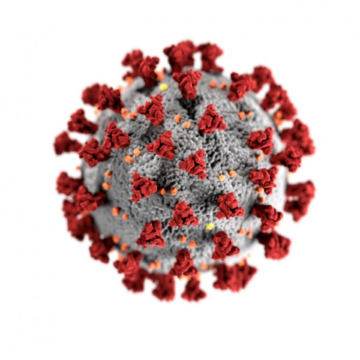

Geoff Dyer: Yeah, it’s a little piece of self-encouragement. Because, you know, sometimes I’m sort of worried about my take on a given subject. Do I know enough about it? Take for example, my history of photography called The Ongoing Moment. I wrote that book because I wanted to find out about the history of photography. I wrote the book for the same reason that readers might later go to it. Granted, the social lives of viruses aren’t quite like those of other species. Viruses don’t post selfies to social media, volunteer at food banks or commit identity theft like humans do. They don’t fight with allies to dominate a troop like baboons; they don’t collect nectar to feed their queen like honeybees; they don’t even congeal into slimy mats for their common defense like some bacteria do. Nevertheless, sociovirologists believe that viruses do

Granted, the social lives of viruses aren’t quite like those of other species. Viruses don’t post selfies to social media, volunteer at food banks or commit identity theft like humans do. They don’t fight with allies to dominate a troop like baboons; they don’t collect nectar to feed their queen like honeybees; they don’t even congeal into slimy mats for their common defense like some bacteria do. Nevertheless, sociovirologists believe that viruses do  Saar Wilf is an ex-Israeli entrepreneur. Since 2016, he’s been developing a new form of reasoning, meant to transcend normal human bias.

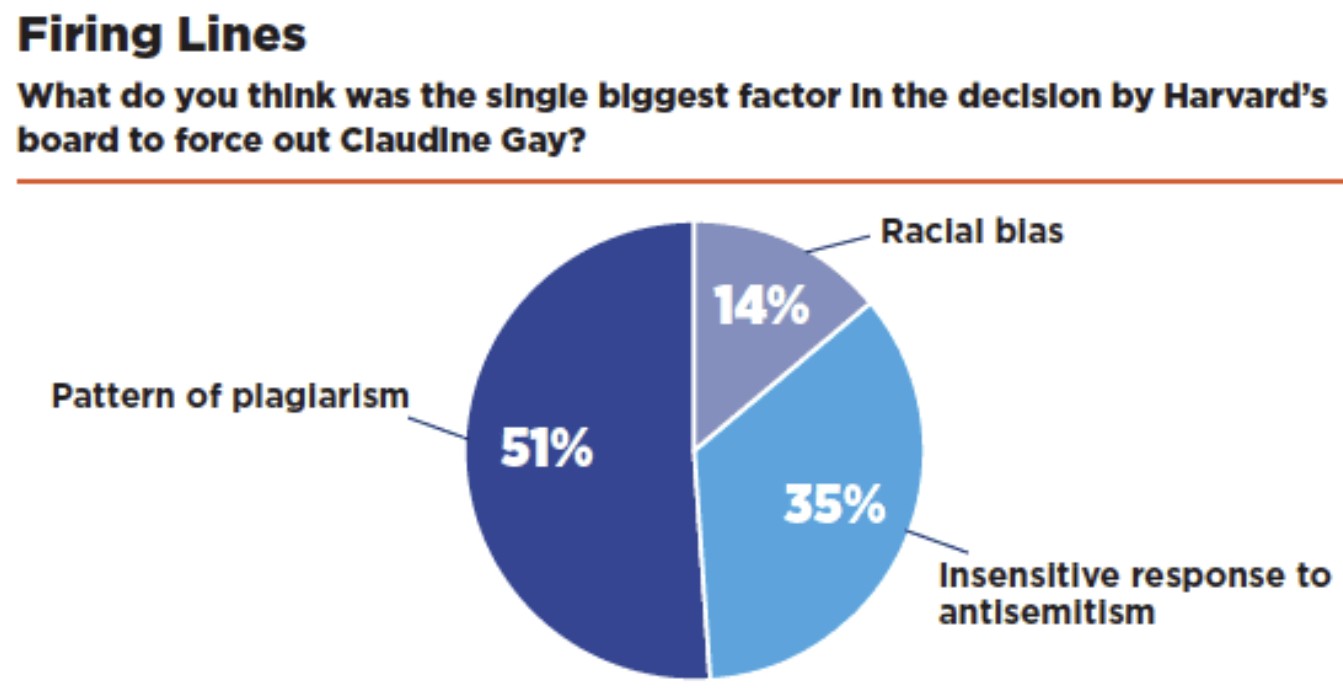

Saar Wilf is an ex-Israeli entrepreneur. Since 2016, he’s been developing a new form of reasoning, meant to transcend normal human bias. The negative buzz over board challenges experienced by Harvard, Tesla and Boeing shows remarkably parallel problems over the same period. Harvard’s stumble is particularly educational for boards facing a governance crisis.

The negative buzz over board challenges experienced by Harvard, Tesla and Boeing shows remarkably parallel problems over the same period. Harvard’s stumble is particularly educational for boards facing a governance crisis.