Field Guide

Once, in the cool blue middle of a lake,

up to my neck in that most precious element of all,

I found the pale gray curled-upwards pigeon feather

floating on the tension of the water

at the very instant when a dragonfly’

like a blue-green iridescent bobby pin

hovered over it, then lit, and rested.

That’s all.

I mentioned this in the same way

that I fold the corner of a page

in certain library books,

so that the next reader will know

where to look for the good parts.

—in the words of New York Times reviewer Dwight Garner:

“At his frequent best … Hoagland is demonically in touch

with the American demotic.”

In 1968, Tversky and Kahneman were both rising stars in the psychology department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They had little else in common. Tversky was born in Israel and had been a military hero. He had a bit of a quiet swagger (along with, incongruously, a slight lisp). He was an optimist, not only because it suited his personality but also because, as he put it, “when you are a pessimist and the bad thing happens, you live it twice. Once when you worry about it, and the second time when it happens.” A night owl, he would often schedule meetings with his graduate students at midnight, over tea, with no one around to bother them.

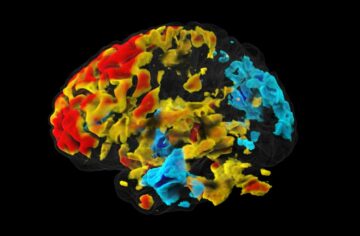

In 1968, Tversky and Kahneman were both rising stars in the psychology department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They had little else in common. Tversky was born in Israel and had been a military hero. He had a bit of a quiet swagger (along with, incongruously, a slight lisp). He was an optimist, not only because it suited his personality but also because, as he put it, “when you are a pessimist and the bad thing happens, you live it twice. Once when you worry about it, and the second time when it happens.” A night owl, he would often schedule meetings with his graduate students at midnight, over tea, with no one around to bother them. Inside the brains of people with psychosis, two key systems are malfunctioning: a “filter” that directs attention toward important external events and internal thoughts, and a “predictor” composed of pathways that anticipate rewards. Dysfunction of these systems makes it difficult to know what’s real, manifesting as hallucinations and delusions. The findings come from a Stanford Medicine-led study, published April 11 in Molecular Psychiatry, that used brain scan data from children, teens and

Inside the brains of people with psychosis, two key systems are malfunctioning: a “filter” that directs attention toward important external events and internal thoughts, and a “predictor” composed of pathways that anticipate rewards. Dysfunction of these systems makes it difficult to know what’s real, manifesting as hallucinations and delusions. The findings come from a Stanford Medicine-led study, published April 11 in Molecular Psychiatry, that used brain scan data from children, teens and  You know the stereotype of the NPR listener: an EV-driving, Wordle-playing, tote bag–carrying coastal elite. It doesn’t precisely describe me, but it’s not far off. I’m Sarah Lawrence–educated, was raised by a

You know the stereotype of the NPR listener: an EV-driving, Wordle-playing, tote bag–carrying coastal elite. It doesn’t precisely describe me, but it’s not far off. I’m Sarah Lawrence–educated, was raised by a  For more than 40 years, Avi Wigderson has studied problems. But as a computational complexity theorist, he doesn’t necessarily care about the answers to these problems. He often just wants to know if they’re solvable or not, and how to tell. “The situation is ridiculous,” said

For more than 40 years, Avi Wigderson has studied problems. But as a computational complexity theorist, he doesn’t necessarily care about the answers to these problems. He often just wants to know if they’re solvable or not, and how to tell. “The situation is ridiculous,” said

From St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, a lane once led through fields up to a small patch of grass. In the centre of this green, where formerly stood a stake, there is now a stone slab engraved: ‘in memory of those accused of witchcraft’. Convicted at trials held in the cathedral, the condemned were marched up the lane with hands bound, lashed to the stake and then ‘wyrried’ – that is strangled to death by the public executioner – and burned to ash. Other forms of execution were available; common criminals and traitors might also be wyrried but not reduced to ashes. Burning, however, was ‘cheust’ – ‘just’ – for witches. Yet the witches were otherwise quite undistinguished: ‘they wur cheust folk’ declares the slab’s main inscription in suitably Orcadian spelling.

From St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, a lane once led through fields up to a small patch of grass. In the centre of this green, where formerly stood a stake, there is now a stone slab engraved: ‘in memory of those accused of witchcraft’. Convicted at trials held in the cathedral, the condemned were marched up the lane with hands bound, lashed to the stake and then ‘wyrried’ – that is strangled to death by the public executioner – and burned to ash. Other forms of execution were available; common criminals and traitors might also be wyrried but not reduced to ashes. Burning, however, was ‘cheust’ – ‘just’ – for witches. Yet the witches were otherwise quite undistinguished: ‘they wur cheust folk’ declares the slab’s main inscription in suitably Orcadian spelling. It was hailed as a potentially transformative technique for measuring brain activity in animals: direct imaging of neuronal activity (DIANA), held the promise of mapping neuronal activity so fast that neurons could be tracked as they fired. But nearly two years on from the

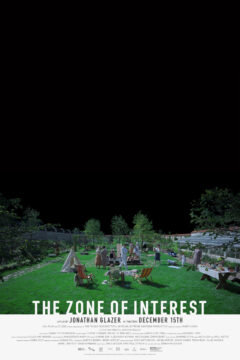

It was hailed as a potentially transformative technique for measuring brain activity in animals: direct imaging of neuronal activity (DIANA), held the promise of mapping neuronal activity so fast that neurons could be tracked as they fired. But nearly two years on from the  Glazer’s decision to only use hidden cameras, without any artificial lighting, creates formal limitations and challenges. But the images retain an intense tactility: patterns on fabrics, the pull of harshly parted and pinned hair, fuzz on a bee that circles a blossom, the softness of a dog’s muzzle, the glint of light reflected from an extracted human tooth. Close-ups punctuate longer observational takes, asserting the specificity of the surfaces that define this moment. The measured pacing of The Zone of Interest strikes me as distinct from the slow cinema tradition, where duration typically serves as a thematic focus. Instead, the length of the shots serves the function of extending the overarching tension. Glazer’s long takes are often paired with an uncomfortable intensity in the soundscape (perhaps the sonic analogue to an uncomfortable close-up), making these moments less an invitation to haptic reverie than an overwhelming of the senses. Suspense, tension, and a nauseating realization about what remains unseen dominate the affect, increased by the long takes that never fully reveal or resolve. The impact feels similar to the way the mind retains a vividly detailed image of a mundane moment preceding a traumatic event that itself can’t be fully recalled.

Glazer’s decision to only use hidden cameras, without any artificial lighting, creates formal limitations and challenges. But the images retain an intense tactility: patterns on fabrics, the pull of harshly parted and pinned hair, fuzz on a bee that circles a blossom, the softness of a dog’s muzzle, the glint of light reflected from an extracted human tooth. Close-ups punctuate longer observational takes, asserting the specificity of the surfaces that define this moment. The measured pacing of The Zone of Interest strikes me as distinct from the slow cinema tradition, where duration typically serves as a thematic focus. Instead, the length of the shots serves the function of extending the overarching tension. Glazer’s long takes are often paired with an uncomfortable intensity in the soundscape (perhaps the sonic analogue to an uncomfortable close-up), making these moments less an invitation to haptic reverie than an overwhelming of the senses. Suspense, tension, and a nauseating realization about what remains unseen dominate the affect, increased by the long takes that never fully reveal or resolve. The impact feels similar to the way the mind retains a vividly detailed image of a mundane moment preceding a traumatic event that itself can’t be fully recalled. We have a sense, I think, of the false border sequestering art from theory. And so to remark on Maggie Nelson’s facility in mating the two is to say the least about how she does so—which is with a hurtling gusto that nonetheless invites us to pause and think. For this, her books are beloved by audiences with varying attachments to the categories that are often, imperfectly, applied to what they are reading: “memoir,” “art criticism,” “poetry,” “queer theory,” “feminism.” This is one way of saying that describing Nelson’s writing can be harder than consuming it, as one of its defining features involves unfurling the shorthand that governs—literally and figuratively—so much of our lives, including the terms we use to identify ourselves.

We have a sense, I think, of the false border sequestering art from theory. And so to remark on Maggie Nelson’s facility in mating the two is to say the least about how she does so—which is with a hurtling gusto that nonetheless invites us to pause and think. For this, her books are beloved by audiences with varying attachments to the categories that are often, imperfectly, applied to what they are reading: “memoir,” “art criticism,” “poetry,” “queer theory,” “feminism.” This is one way of saying that describing Nelson’s writing can be harder than consuming it, as one of its defining features involves unfurling the shorthand that governs—literally and figuratively—so much of our lives, including the terms we use to identify ourselves. In 1968

In 1968 Daniel Kahneman died last week at the age of 90. His legacy is immense. He was, as he put it, the “grandfather” of behavioural economics — think economics but with a realistic model of what a human is — a role which won him a Nobel Prize. But Kahneman’s legacy is bigger than that. Kahneman and Tversky changed how we think about how people think, and if you change that, you change everything. You can see their influence all across the social sciences and much of the humanities.

Daniel Kahneman died last week at the age of 90. His legacy is immense. He was, as he put it, the “grandfather” of behavioural economics — think economics but with a realistic model of what a human is — a role which won him a Nobel Prize. But Kahneman’s legacy is bigger than that. Kahneman and Tversky changed how we think about how people think, and if you change that, you change everything. You can see their influence all across the social sciences and much of the humanities. The detective in a typical British crime procedural would say that

The detective in a typical British crime procedural would say that