Audrey Wasser at nonsite:

What would it mean to subtract context from writing, in each and every sense of “context” that Derrida proposes here? And would this be a remotely helpful exercise for thinking about the relation between text and context in literary studies? It’s hard to see how it could be. Even the strongest statements I can think of urging critics to turn away from context—take Rita Felski’s essay “Context Stinks!,” the last chapter of her Limits of Critique, or Joseph North’s arguments against the historicist/contextualist paradigm in Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History—even these apparently hardline positions in no way advocate for a total absenting of every form of contextual consideration. Rather, each seeks to limit appeals to certain contexts in order to boost the visibility of others. North, for example, seeks to challenge the priority placed on historical scholarship in order to shed light on present contexts of aesthetic education. For him, historical scholarship has become overly specialized and no longer realizes its vocation “to intervene in the ‘culture as a whole.’”4 Felski, for her part, wants to tamp down what she calls “fealty to the clarifying power of historical context” because she sees such fealty as engaging in a sort of one-upmanship of insight.

What would it mean to subtract context from writing, in each and every sense of “context” that Derrida proposes here? And would this be a remotely helpful exercise for thinking about the relation between text and context in literary studies? It’s hard to see how it could be. Even the strongest statements I can think of urging critics to turn away from context—take Rita Felski’s essay “Context Stinks!,” the last chapter of her Limits of Critique, or Joseph North’s arguments against the historicist/contextualist paradigm in Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History—even these apparently hardline positions in no way advocate for a total absenting of every form of contextual consideration. Rather, each seeks to limit appeals to certain contexts in order to boost the visibility of others. North, for example, seeks to challenge the priority placed on historical scholarship in order to shed light on present contexts of aesthetic education. For him, historical scholarship has become overly specialized and no longer realizes its vocation “to intervene in the ‘culture as a whole.’”4 Felski, for her part, wants to tamp down what she calls “fealty to the clarifying power of historical context” because she sees such fealty as engaging in a sort of one-upmanship of insight.

more here.

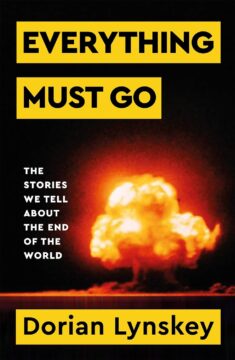

Evidently, the time is ripe for a survey of the branch of cultural production concerned with the end of the world. And yet, as Lynskey points out, tales have been told about it for as long as we’ve been doing story. J G Ballard, whose work is given rich and perceptive attention in the chapter ‘Catastrophe’, wrote in 1977: ‘I would guess that from man’s first inkling of this planet as a single entity existing independently of himself came the determination to bring about its destruction.’

Evidently, the time is ripe for a survey of the branch of cultural production concerned with the end of the world. And yet, as Lynskey points out, tales have been told about it for as long as we’ve been doing story. J G Ballard, whose work is given rich and perceptive attention in the chapter ‘Catastrophe’, wrote in 1977: ‘I would guess that from man’s first inkling of this planet as a single entity existing independently of himself came the determination to bring about its destruction.’ Most of us think of inflammation as the redness and swelling that follow a wound, infection or injury, such as an ankle sprain, or from overdoing a sport, “tennis elbow,” for example. This is “acute” inflammation, a beneficial immune system response that encourages healing, and usually disappears once the injury improves.

Most of us think of inflammation as the redness and swelling that follow a wound, infection or injury, such as an ankle sprain, or from overdoing a sport, “tennis elbow,” for example. This is “acute” inflammation, a beneficial immune system response that encourages healing, and usually disappears once the injury improves. In need of silence, I booked a room at a Trappist monastery. The following Friday, I snuck out of work early and headed south, not realizing that Ava, Missouri, was four hours away, down at the border of Arkansas. I sped down the interstate, glided off the exit ramp—and got stuck behind a livestock trailer. For the next hour, as we crept along a narrow country road, the wide face of a brown and white cow gazed back at me. Its fuzzy ears stuck straight out, like they had been glued on at the last minute. Lashes curled above steady brown eyes that held a lifetime’s observations.

In need of silence, I booked a room at a Trappist monastery. The following Friday, I snuck out of work early and headed south, not realizing that Ava, Missouri, was four hours away, down at the border of Arkansas. I sped down the interstate, glided off the exit ramp—and got stuck behind a livestock trailer. For the next hour, as we crept along a narrow country road, the wide face of a brown and white cow gazed back at me. Its fuzzy ears stuck straight out, like they had been glued on at the last minute. Lashes curled above steady brown eyes that held a lifetime’s observations. The endangered bonobo, the great ape of the Central African rainforest, has a reputation for being a bit of a hippie. Known as more peaceful than their warring chimpanzee cousins, bonobos live in matriarchal societies, engage in recreational sex, and display signs of

The endangered bonobo, the great ape of the Central African rainforest, has a reputation for being a bit of a hippie. Known as more peaceful than their warring chimpanzee cousins, bonobos live in matriarchal societies, engage in recreational sex, and display signs of  I do not deny that there has been a shocking and upsetting rise in antisemitism over the last few months, including several instances of antisemitism right at Yale and in New Haven. Last fall, one professor’s post on X (formerly Twitter) appearing to praise Hamas’ October 7th attack sparked a petition for her to be fired.

I do not deny that there has been a shocking and upsetting rise in antisemitism over the last few months, including several instances of antisemitism right at Yale and in New Haven. Last fall, one professor’s post on X (formerly Twitter) appearing to praise Hamas’ October 7th attack sparked a petition for her to be fired.

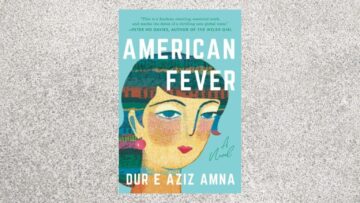

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation.

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation. TAKE A GOOD LOOK

TAKE A GOOD LOOK Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things.

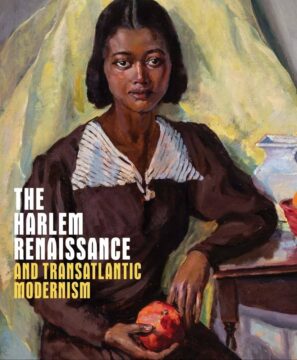

Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things. “For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”