Adam Frank in Aeon:

Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the Universe beyond Earth is having its day in the sun. The next big multibillion-dollar space telescope (the successor to the James Webb) will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets and NASA has a robust, well-funded programme in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to United States congressional testimony with wild claims of government programmes hiding crashed saucers, UFOs and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes.

Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the Universe beyond Earth is having its day in the sun. The next big multibillion-dollar space telescope (the successor to the James Webb) will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets and NASA has a robust, well-funded programme in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to United States congressional testimony with wild claims of government programmes hiding crashed saucers, UFOs and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes.

What are we to make of these twin movements, the scientific search for life on one hand, and the endlessly murky waters of UFO/UAP claims on the other? Looking at history shows that these two very different approaches to the question of extraterrestrial life are, in fact, linked, but not in a good way.

More here.

Chip Walter’s new book is titled “Immortality Inc.: Renegade Science, Silicon Valley Billions and the Quest to Live Forever.” It’s about the money, and the research, that’s seeking a way to extend human life indefinitely. Sounds like science fiction, but Walter thinks breakthroughs are just around the corner. “I think it’s going to begin to happen in the next five years,” said the Pittsburgh-based science writer in a recent interview.

Chip Walter’s new book is titled “Immortality Inc.: Renegade Science, Silicon Valley Billions and the Quest to Live Forever.” It’s about the money, and the research, that’s seeking a way to extend human life indefinitely. Sounds like science fiction, but Walter thinks breakthroughs are just around the corner. “I think it’s going to begin to happen in the next five years,” said the Pittsburgh-based science writer in a recent interview. Stem-cell researcher Carolina Florian didn’t trust what she was seeing. Her elderly laboratory mice were starting to look younger. They were more sprightly and their coats were sleeker. Yet all she had done was to briefly treat them — many weeks earlier — with a drug that corrected the organization of proteins inside a type of stem cell. When technicians who were replicating her experiment in two other labs found the same thing, she started to feel more confident that the treatment was somehow rejuvenating the animals. In two papers, in 2020 and 2022, her team described how the approach extends the lifespan of mice and keeps them fit into old age

Stem-cell researcher Carolina Florian didn’t trust what she was seeing. Her elderly laboratory mice were starting to look younger. They were more sprightly and their coats were sleeker. Yet all she had done was to briefly treat them — many weeks earlier — with a drug that corrected the organization of proteins inside a type of stem cell. When technicians who were replicating her experiment in two other labs found the same thing, she started to feel more confident that the treatment was somehow rejuvenating the animals. In two papers, in 2020 and 2022, her team described how the approach extends the lifespan of mice and keeps them fit into old age Religion reinforced Ptolemaic queenship. The influential Egyptian priesthood and the Ptolemaic court were politically co-dependent. In discussing this relationship, the author makes skilful use of the art and hieroglyphs found in Egypt’s temples. These showcased favourably the role of the Ptolemaic queen, hedging it with a prestigious divinity. How much this ‘propaganda’ rubbed off on ordinary Egyptians is debatable. Llewellyn-Jones also highlights the colonialist and racist character of the Graeco-Macedonian occupation of Egypt and describes the so-called Great Revolt of around 199 BC. Setting southern Egypt alight, it was put down by Alexandria only after a real show of force.

Religion reinforced Ptolemaic queenship. The influential Egyptian priesthood and the Ptolemaic court were politically co-dependent. In discussing this relationship, the author makes skilful use of the art and hieroglyphs found in Egypt’s temples. These showcased favourably the role of the Ptolemaic queen, hedging it with a prestigious divinity. How much this ‘propaganda’ rubbed off on ordinary Egyptians is debatable. Llewellyn-Jones also highlights the colonialist and racist character of the Graeco-Macedonian occupation of Egypt and describes the so-called Great Revolt of around 199 BC. Setting southern Egypt alight, it was put down by Alexandria only after a real show of force. To answer the question of what we’re losing, think about what nightlife has given us. It was always a haven for outsiders trying to find, establish or shape their own communities. It brings people together and remains an insistently communal experience in an increasingly individualistic and closed-off late capitalist society. Gigs and clubs require us to be together – as friends, but also with those we don’t know. Luis Manuel Garcia-Mispireta, an academic who researches dance-music scenes, calls this “

To answer the question of what we’re losing, think about what nightlife has given us. It was always a haven for outsiders trying to find, establish or shape their own communities. It brings people together and remains an insistently communal experience in an increasingly individualistic and closed-off late capitalist society. Gigs and clubs require us to be together – as friends, but also with those we don’t know. Luis Manuel Garcia-Mispireta, an academic who researches dance-music scenes, calls this “ Our sun is the best-observed star in the entire universe.

Our sun is the best-observed star in the entire universe. I was meeting my mother at the museum. My mother is both a great lover of art and completely unpretentious about it. Often, she simply stands in front of objects of art and smiles. We found ourselves in an exhibit entitled Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting. We were both suddenly astonished. I don’t know why exactly. I do know why un-exactly. The paintings are extraordinary. But what does that mean? I don’t know. I don’t know anything about Indian Court paintings. I’ve seen a few here and there, including some in India. But I don’t know how to look at them. I don’t know the history or the context or the way that these paintings fit into a narrative. I don’t know the codes. So I just looked, without context, without codes.

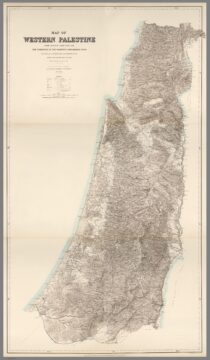

I was meeting my mother at the museum. My mother is both a great lover of art and completely unpretentious about it. Often, she simply stands in front of objects of art and smiles. We found ourselves in an exhibit entitled Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting. We were both suddenly astonished. I don’t know why exactly. I do know why un-exactly. The paintings are extraordinary. But what does that mean? I don’t know. I don’t know anything about Indian Court paintings. I’ve seen a few here and there, including some in India. But I don’t know how to look at them. I don’t know the history or the context or the way that these paintings fit into a narrative. I don’t know the codes. So I just looked, without context, without codes. Palestine, before it named something else, named a region. The region emerged during Ottoman rule, between 1518 and 1920. It was called Filastin in Arabic, the language of the Muslims, Christians, Jews and others who lived in this region. The word « Palestinians » could apply to all of them. It could refer to « Palestinians » beyond Palestine, too, as when Immanuel Kant, for example, referred to European Jews in 1798 as « Palestinians living among us » in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. This is one of many things we’ve forgotten to remember.

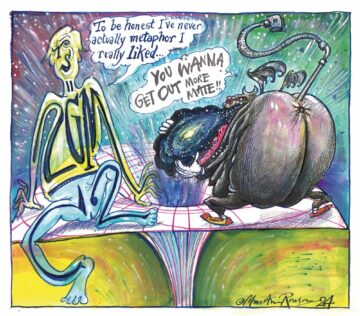

Palestine, before it named something else, named a region. The region emerged during Ottoman rule, between 1518 and 1920. It was called Filastin in Arabic, the language of the Muslims, Christians, Jews and others who lived in this region. The word « Palestinians » could apply to all of them. It could refer to « Palestinians » beyond Palestine, too, as when Immanuel Kant, for example, referred to European Jews in 1798 as « Palestinians living among us » in his Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View. This is one of many things we’ve forgotten to remember. If science has a native tongue, it is mathematics. Equations capture, precisely, the relationships among the elements of a system; they allow us to pose questions and calculate answers. Numerically, these answers are precise and unambiguous – but what happens when we want to know what our calculations mean? Well, that is when we revert to our own native tongue: metaphor.

If science has a native tongue, it is mathematics. Equations capture, precisely, the relationships among the elements of a system; they allow us to pose questions and calculate answers. Numerically, these answers are precise and unambiguous – but what happens when we want to know what our calculations mean? Well, that is when we revert to our own native tongue: metaphor. An orangutan in Sumatra surprised scientists when he was seen treating an open wound on his cheek with a poultice made from a medicinal plant. It’s the first scientific record of a wild animal healing a wound using a plant with known medicinal properties. The findings were published this week in Scientific Reports

An orangutan in Sumatra surprised scientists when he was seen treating an open wound on his cheek with a poultice made from a medicinal plant. It’s the first scientific record of a wild animal healing a wound using a plant with known medicinal properties. The findings were published this week in Scientific Reports O

O