KC Hoard at The Walrus:

Court and Spark starts in a familiar Jonian fashion: mournful piano chords, poetic lyrics, Mitchell’s skyscraper voice. “Love came to my door with a sleeping roll and a madman’s soul,” she coos. “He thought for sure I’d seen him dancing in a river in the dark, looking for a woman to court and spark.” But when she unfurls the title of the album, something unexpected appears: a stuttering hi-hat. A beat in a Joni Mitchell song. And with that rhythm, the Joni of the past was gone. Joni the Confessional Poet, Joni the Selfish and Sad, Joni the Lonely Painter was no more.

By 1974, Mitchell had grown tired of her old style. “I feel miscast in some of the songs that I wrote as a younger woman,” she told CBC Radio a couple weeks after Court and Spark’s release. “You know, you wouldn’t ask Picasso to go back and paint from his Blue Period.” She was done playing the starry-eyed hippie. She was tired of singing dirges. She wanted to find new, challenging, exciting ways to write pop music.

more here.

Many other fine pieces in the Central Exhibition are textile-based: a dense, earthy slab of threads by the Colombian Olga de Amaral, who turns ninety-two this year; a selection of embroidered burlap pieces by the anonymous Chileans known as Arpilleristas; large, cool compositions by Susanne Wenger, who spent most of her long life in Nigeria, practicing the Yoruba religion and mastering batik, the art of wax-resist dyeing. Her pieces, which show mortals and deities floating side by side, stick to the same spiky patterns and subdued hues but never retrace their steps; you could imagine them continuing forever, and might well want them to. If not, walk a few feet to the exhibition’s other main batik specialist, Ṣàngódáre Gbádégẹsin Àjàlá, who passed away in 2021. His creations are as religiously inclined as Wenger’s—he was her adopted son—but with a livelier clamor of bodies pressed together. There’s almost too much to savor; the intricate coloring, combined with pale spiderweb shading, gives the figures a pimpled texture I can’t remember seeing in art before and now can’t stop noticing everywhere. Àjàlá, Wenger, and the rest of the fibre brigade may be the snappiest retort to the gripe that there are too many dead artists this year: when we’re dealing with textiles, one of the oldest visual art forms and still backlogged with brilliance, the distinction between new and old stops mattering so much. Good is good, even if it takes decades for anyone to notice.

Many other fine pieces in the Central Exhibition are textile-based: a dense, earthy slab of threads by the Colombian Olga de Amaral, who turns ninety-two this year; a selection of embroidered burlap pieces by the anonymous Chileans known as Arpilleristas; large, cool compositions by Susanne Wenger, who spent most of her long life in Nigeria, practicing the Yoruba religion and mastering batik, the art of wax-resist dyeing. Her pieces, which show mortals and deities floating side by side, stick to the same spiky patterns and subdued hues but never retrace their steps; you could imagine them continuing forever, and might well want them to. If not, walk a few feet to the exhibition’s other main batik specialist, Ṣàngódáre Gbádégẹsin Àjàlá, who passed away in 2021. His creations are as religiously inclined as Wenger’s—he was her adopted son—but with a livelier clamor of bodies pressed together. There’s almost too much to savor; the intricate coloring, combined with pale spiderweb shading, gives the figures a pimpled texture I can’t remember seeing in art before and now can’t stop noticing everywhere. Àjàlá, Wenger, and the rest of the fibre brigade may be the snappiest retort to the gripe that there are too many dead artists this year: when we’re dealing with textiles, one of the oldest visual art forms and still backlogged with brilliance, the distinction between new and old stops mattering so much. Good is good, even if it takes decades for anyone to notice. Chances are, if you have put on a few pounds, the cause is deeper than eating too much junk food or skipping one too many workouts. Chronic, low-grade

Chances are, if you have put on a few pounds, the cause is deeper than eating too much junk food or skipping one too many workouts. Chronic, low-grade  In some birding circles, people say that anyone who looks at birds is a birder — a kind, inclusive sentiment that overlooks the forces that create and shape subcultures. Anyone can dance, but not everyone would identify as a dancer, because the term suggests, if not skill, then at least effort and intent. Similarly, I’ve cared about birds and other animals for my entire life, and I’ve written about them throughout my two decades as a science writer, but I mark the moment when I specifically chose to devote time and energy to them as the moment I became a birder.

In some birding circles, people say that anyone who looks at birds is a birder — a kind, inclusive sentiment that overlooks the forces that create and shape subcultures. Anyone can dance, but not everyone would identify as a dancer, because the term suggests, if not skill, then at least effort and intent. Similarly, I’ve cared about birds and other animals for my entire life, and I’ve written about them throughout my two decades as a science writer, but I mark the moment when I specifically chose to devote time and energy to them as the moment I became a birder. Few computer science breakthroughs have done so much in so little time as the artificial intelligence design known as a transformer. A transformer is a form of deep learning—a machine model based on networks in the brain—that researchers at Google

Few computer science breakthroughs have done so much in so little time as the artificial intelligence design known as a transformer. A transformer is a form of deep learning—a machine model based on networks in the brain—that researchers at Google  The system that evolved in the last quarter of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic came to be called neoliberalism. “Liberal” refers to being “free,” in this context, free of government intervention including regulations. The “neo” meant to suggest that there was something new in it; in reality, it was little different from the liberalism and laissez-faire doctrines of the nineteenth century that advised: “leave it to the market.”

The system that evolved in the last quarter of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic came to be called neoliberalism. “Liberal” refers to being “free,” in this context, free of government intervention including regulations. The “neo” meant to suggest that there was something new in it; in reality, it was little different from the liberalism and laissez-faire doctrines of the nineteenth century that advised: “leave it to the market.” I

I Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the Universe beyond Earth is having its day in the sun. The next big multibillion-dollar space telescope (the successor to the James Webb) will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets and NASA has a robust, well-funded programme in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to United States congressional testimony with wild claims of government programmes hiding crashed saucers, UFOs and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes.

Suddenly, everyone is talking about aliens. After decades on the cultural margins, the question of life in the Universe beyond Earth is having its day in the sun. The next big multibillion-dollar space telescope (the successor to the James Webb) will be tuned to search for signatures of alien life on alien planets and NASA has a robust, well-funded programme in astrobiology. Meanwhile, from breathless newspaper articles about unexplained navy pilot sightings to United States congressional testimony with wild claims of government programmes hiding crashed saucers, UFOs and UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena) seem to be making their own journey from the fringes. Because the likelihood of

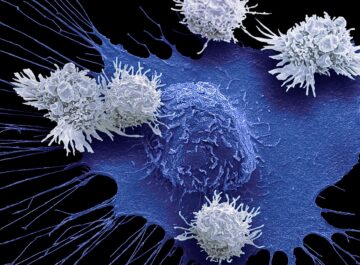

Because the likelihood of  US drug regulators dropped a bombshell in November 2023 when they announced an investigation into one of the most celebrated cancer treatments to emerge in decades. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it was looking at whether a strategy that involves engineering a person’s immune cells to kill cancer was leading to new malignancies in people who had been treated with it.

US drug regulators dropped a bombshell in November 2023 when they announced an investigation into one of the most celebrated cancer treatments to emerge in decades. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it was looking at whether a strategy that involves engineering a person’s immune cells to kill cancer was leading to new malignancies in people who had been treated with it. In my essay “

In my essay “ Start talking to

Start talking to  If we do pay attention, it is not hard to see that capital’s mutation into what I call cloud capital has demolished capitalism’s two pillars: markets and profits. Of course, markets and profits remain ubiquitous—indeed, markets and profits were ubiquitous under feudalism too—they just aren’t running the show anymore. What has happened over the last two decades is that profit and markets have been evicted from the epicenter of our economic and social system, pushed out to its margins, and replaced. With what? Markets, the medium of capitalism, have been replaced by digital trading platforms which look like, but are not, markets, and are better understood as fiefdoms. And profit, the engine of capitalism, has been replaced with its feudal predecessor: rent. Specifically, it is a form of rent that must be paid for access to those platforms and to the cloud more broadly. I call it cloud rent. As a result, real power today resides not with the owners of traditional capital, such as machinery, buildings, railway and phone networks, industrial robots. They continue to extract profits from workers, from waged labor, but they are not in charge as they once were. They have become vassals in relation to a new class of feudal overlord, the owners of cloud capital. As for the rest of us, we have returned to our former status as serfs, contributing to the wealth and power of the new ruling class with our unpaid labor—in addition to the waged labor we perform, when we get the chance.

If we do pay attention, it is not hard to see that capital’s mutation into what I call cloud capital has demolished capitalism’s two pillars: markets and profits. Of course, markets and profits remain ubiquitous—indeed, markets and profits were ubiquitous under feudalism too—they just aren’t running the show anymore. What has happened over the last two decades is that profit and markets have been evicted from the epicenter of our economic and social system, pushed out to its margins, and replaced. With what? Markets, the medium of capitalism, have been replaced by digital trading platforms which look like, but are not, markets, and are better understood as fiefdoms. And profit, the engine of capitalism, has been replaced with its feudal predecessor: rent. Specifically, it is a form of rent that must be paid for access to those platforms and to the cloud more broadly. I call it cloud rent. As a result, real power today resides not with the owners of traditional capital, such as machinery, buildings, railway and phone networks, industrial robots. They continue to extract profits from workers, from waged labor, but they are not in charge as they once were. They have become vassals in relation to a new class of feudal overlord, the owners of cloud capital. As for the rest of us, we have returned to our former status as serfs, contributing to the wealth and power of the new ruling class with our unpaid labor—in addition to the waged labor we perform, when we get the chance. It is today my belief that once ordinary language is laughed out of the room, philosophical theories are no longer held responsible at all to the ways we actually speak and actually live. And aren’t the humanities ultimately for a good part connected to how we actually speak and live? To me, it is clear that the descriptions of human life we find in the novels of Samuel Beckett or in the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi are not mere entertainment. In my view, and among other things, they teach us to perceive and describe what goes on in social and individual life. To echo what Hilary Putnam once said, contempt for ordinary language is, at bottom, contempt for the humanities.

It is today my belief that once ordinary language is laughed out of the room, philosophical theories are no longer held responsible at all to the ways we actually speak and actually live. And aren’t the humanities ultimately for a good part connected to how we actually speak and live? To me, it is clear that the descriptions of human life we find in the novels of Samuel Beckett or in the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi are not mere entertainment. In my view, and among other things, they teach us to perceive and describe what goes on in social and individual life. To echo what Hilary Putnam once said, contempt for ordinary language is, at bottom, contempt for the humanities. T

T