Jeannette Cooperman in The Common Reader:

In need of silence, I booked a room at a Trappist monastery. The following Friday, I snuck out of work early and headed south, not realizing that Ava, Missouri, was four hours away, down at the border of Arkansas. I sped down the interstate, glided off the exit ramp—and got stuck behind a livestock trailer. For the next hour, as we crept along a narrow country road, the wide face of a brown and white cow gazed back at me. Its fuzzy ears stuck straight out, like they had been glued on at the last minute. Lashes curled above steady brown eyes that held a lifetime’s observations.

In need of silence, I booked a room at a Trappist monastery. The following Friday, I snuck out of work early and headed south, not realizing that Ava, Missouri, was four hours away, down at the border of Arkansas. I sped down the interstate, glided off the exit ramp—and got stuck behind a livestock trailer. For the next hour, as we crept along a narrow country road, the wide face of a brown and white cow gazed back at me. Its fuzzy ears stuck straight out, like they had been glued on at the last minute. Lashes curled above steady brown eyes that held a lifetime’s observations.

There was no way to pass that trailer. I know because I kept trying, agitated, for the first three miles. The cow watched. Where it was heading, how idyllic or ominous its destination, I had no idea; nor did the cow know. Sighing, I downshifted, resigning myself to lost time. The cow held my gaze. The future fell away.

Slowly, a calm stole over me. By the time the road widened, I had no desire to go around. The placid look on that cow’s face—wordless, accepting—had righted my universe.

More here.

The endangered bonobo, the great ape of the Central African rainforest, has a reputation for being a bit of a hippie. Known as more peaceful than their warring chimpanzee cousins, bonobos live in matriarchal societies, engage in recreational sex, and display signs of

The endangered bonobo, the great ape of the Central African rainforest, has a reputation for being a bit of a hippie. Known as more peaceful than their warring chimpanzee cousins, bonobos live in matriarchal societies, engage in recreational sex, and display signs of  I do not deny that there has been a shocking and upsetting rise in antisemitism over the last few months, including several instances of antisemitism right at Yale and in New Haven. Last fall, one professor’s post on X (formerly Twitter) appearing to praise Hamas’ October 7th attack sparked a petition for her to be fired.

I do not deny that there has been a shocking and upsetting rise in antisemitism over the last few months, including several instances of antisemitism right at Yale and in New Haven. Last fall, one professor’s post on X (formerly Twitter) appearing to praise Hamas’ October 7th attack sparked a petition for her to be fired.

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation.

In Dur e Aziz Amna’s gorgeous debut, American Fever, readers can expect to find all the hallmarks of a bumpy adolescence—destructive confidence, crippling self-doubt, steamy crushes, social gaffes, obsession with looks and style, and pervasive loneliness. But within this jewel-box of a novel, these universal qualities unfold in a most unusual situation. TAKE A GOOD LOOK

TAKE A GOOD LOOK Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things.

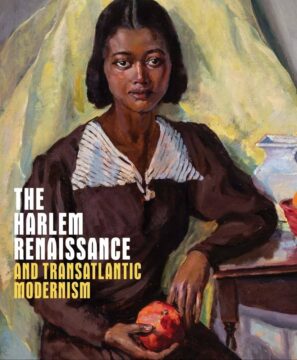

Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things. “For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.” Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice.

Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice. In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that

In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that  Dubbed “living drugs,” CAR T cells are bioengineered from a patient’s own immune cells to make them better able to hunt and destroy cancer. The treatment is successfully tackling previously untreatable blood cancers. Six therapies are already approved by the FDA.

Dubbed “living drugs,” CAR T cells are bioengineered from a patient’s own immune cells to make them better able to hunt and destroy cancer. The treatment is successfully tackling previously untreatable blood cancers. Six therapies are already approved by the FDA.