Clifford Thompson at Commonweal:

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

However, Locke added, “By shedding the old chrysalis of the Negro problem we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation.” That emancipation largely took the form of creative expression—the literature, music, and visual art that flowered in the 1920s and ’30s and reflected the experiences of millions of African Americans who, seeking opportunity, migrated from the South to the cities of the North and Midwest.

more here.

Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice.

Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice. In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that

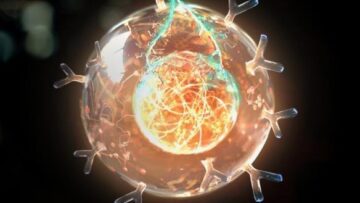

In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that  Dubbed “living drugs,” CAR T cells are bioengineered from a patient’s own immune cells to make them better able to hunt and destroy cancer. The treatment is successfully tackling previously untreatable blood cancers. Six therapies are already approved by the FDA.

Dubbed “living drugs,” CAR T cells are bioengineered from a patient’s own immune cells to make them better able to hunt and destroy cancer. The treatment is successfully tackling previously untreatable blood cancers. Six therapies are already approved by the FDA.  Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew.

Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew. After they were released from prison in Paris in the late autumn of 1794, both having narrowly escaped the guillotine, new bosom friends Rose de Beauharnais and Térézia Tallien found they had nothing to wear. Dressmakers and milliners had all but disappeared from a city still reeling from the Reign of Terror. In an era of desperate need and rampant inflation, a time when even the most prosperous took candles and bread with them when they went out to dinner, who could afford a silk dress, still less stays, hoops, acres of petticoats and several maids to sew you into it?

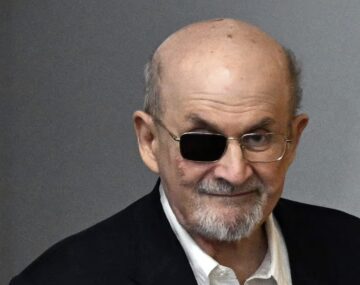

After they were released from prison in Paris in the late autumn of 1794, both having narrowly escaped the guillotine, new bosom friends Rose de Beauharnais and Térézia Tallien found they had nothing to wear. Dressmakers and milliners had all but disappeared from a city still reeling from the Reign of Terror. In an era of desperate need and rampant inflation, a time when even the most prosperous took candles and bread with them when they went out to dinner, who could afford a silk dress, still less stays, hoops, acres of petticoats and several maids to sew you into it? ‘At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife,” begins Salman Rushdie’s new memoir.

‘At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife,” begins Salman Rushdie’s new memoir. NASA’s interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the

NASA’s interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the  Kwame Anthony Appiah is a British-Ghanaian philosopher, Professor of Philosophy and Law and New York University, and the “Ethicist” columnist for The New York Times Magazine.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is a British-Ghanaian philosopher, Professor of Philosophy and Law and New York University, and the “Ethicist” columnist for The New York Times Magazine. “Where is Ahmad?” The soldier called my name while we were stopped at the last Israeli checkpoint on the way from Ramallah to Jerusalem. I am a Palestinian American. But once I’m in my ancestral homeland, I’m not an American in the eyes of Israeli authorities. I am simply Palestinian, denied the basic right to movement and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For too long, Palestinians in the diaspora, like myself, became travelers on our soil. We tried to forget the realities of occupation in the West Bank, and that a few hours south in Gaza our brothers and sisters suffered under even more

“Where is Ahmad?” The soldier called my name while we were stopped at the last Israeli checkpoint on the way from Ramallah to Jerusalem. I am a Palestinian American. But once I’m in my ancestral homeland, I’m not an American in the eyes of Israeli authorities. I am simply Palestinian, denied the basic right to movement and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For too long, Palestinians in the diaspora, like myself, became travelers on our soil. We tried to forget the realities of occupation in the West Bank, and that a few hours south in Gaza our brothers and sisters suffered under even more  If you put a lab mouse on a diet, cutting the animal’s caloric intake by 30 to 40 percent, it will live, on average, about 30 percent longer. The calorie restriction, as the intervention is technically called, can’t be so extreme that the animal is malnourished, but it should be aggressive enough to trigger some key biological changes. Scientists

If you put a lab mouse on a diet, cutting the animal’s caloric intake by 30 to 40 percent, it will live, on average, about 30 percent longer. The calorie restriction, as the intervention is technically called, can’t be so extreme that the animal is malnourished, but it should be aggressive enough to trigger some key biological changes. Scientists  Kant’s views here are taken by many philosophers to be an impossible attempt to have it both ways. Kant seems to be arguing that evil is necessarily attributed to each of us, apparently rooted in human nature. And yet at the same time he claims that evil is freely chosen: each of us is fully responsible for this unavoidable human predicament. But how is this possible? How could a condition “entwined with humanity itself” be something that “come[s] about through one’s own fault”?

Kant’s views here are taken by many philosophers to be an impossible attempt to have it both ways. Kant seems to be arguing that evil is necessarily attributed to each of us, apparently rooted in human nature. And yet at the same time he claims that evil is freely chosen: each of us is fully responsible for this unavoidable human predicament. But how is this possible? How could a condition “entwined with humanity itself” be something that “come[s] about through one’s own fault”? Today, Le Samouraï is recognized as a foundational example of neo-noir, and as a spark that lit a fire under Scorsese, Mann, Tarantino, Jarmusch, Woo, Fincher, et al.—see Taxi Driver (1976), Thief (1981), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Ghost Dog (1999), The Killer (1989), and The Killer (2023). Even the Matrix and John Wick franchises are suffused with references to its cult mythology: aloof antiheroes with sharp suits and slick autos pursued on all sides as they stalk through moody cityscapes, inescapably hurtling toward the violent resolution of their own personal destiny? Check. Such respect and veneration from his American and international peers was something the Stetson- and Ray-Ban-sporting Melville, who functioned as something of a godfather to Jean-Luc Godard and the nascent French New Wave, would have been pleased to receive. Unfortunately, his own dramatic personal destiny was to intervene. In 1973, at only fifty-five, the filmmaker suffered a fatal heart attack over lunch while discussing his next picture—a spy thriller set to star Yves Montand and Catherine Deneuve, never to witness the explosive chain reaction in mainstream cinema that his unapologetic, maverick methods had set off.

Today, Le Samouraï is recognized as a foundational example of neo-noir, and as a spark that lit a fire under Scorsese, Mann, Tarantino, Jarmusch, Woo, Fincher, et al.—see Taxi Driver (1976), Thief (1981), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Ghost Dog (1999), The Killer (1989), and The Killer (2023). Even the Matrix and John Wick franchises are suffused with references to its cult mythology: aloof antiheroes with sharp suits and slick autos pursued on all sides as they stalk through moody cityscapes, inescapably hurtling toward the violent resolution of their own personal destiny? Check. Such respect and veneration from his American and international peers was something the Stetson- and Ray-Ban-sporting Melville, who functioned as something of a godfather to Jean-Luc Godard and the nascent French New Wave, would have been pleased to receive. Unfortunately, his own dramatic personal destiny was to intervene. In 1973, at only fifty-five, the filmmaker suffered a fatal heart attack over lunch while discussing his next picture—a spy thriller set to star Yves Montand and Catherine Deneuve, never to witness the explosive chain reaction in mainstream cinema that his unapologetic, maverick methods had set off. IN OUT OF PLACE: A Memoir (1999), Edward Said recalls that after graduating from Princeton in June 1957, he was torn by “differing impulses”: he could pursue a fellowship from Harvard for graduate study or return to Cairo to work at his father’s stationery company. Eventually, Said deferred Harvard for a year and returned to “sample the Cairo life.” Said claimed that he had no interest in his father’s business, and in the memoir, he recalls how he spent his afternoons in his father’s office: “I would either read—I remember I spent a week reading all through Auden, another leafing through the Pléiade edition of Alain […]—or I would write poetry (some of which I published in Beirut), music criticism, or letters to various friends.” Two decades after Said’s death, we finally have access to 19 of these poems, written between 1956 and 1968, which have been compiled and edited by his biographer, Timothy Brennan, as Songs of an Eastern Humanist (2024).

IN OUT OF PLACE: A Memoir (1999), Edward Said recalls that after graduating from Princeton in June 1957, he was torn by “differing impulses”: he could pursue a fellowship from Harvard for graduate study or return to Cairo to work at his father’s stationery company. Eventually, Said deferred Harvard for a year and returned to “sample the Cairo life.” Said claimed that he had no interest in his father’s business, and in the memoir, he recalls how he spent his afternoons in his father’s office: “I would either read—I remember I spent a week reading all through Auden, another leafing through the Pléiade edition of Alain […]—or I would write poetry (some of which I published in Beirut), music criticism, or letters to various friends.” Two decades after Said’s death, we finally have access to 19 of these poems, written between 1956 and 1968, which have been compiled and edited by his biographer, Timothy Brennan, as Songs of an Eastern Humanist (2024). In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that

In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that